INDIAN VILLAGE (AMERICAN INDIAN VILLAGE)

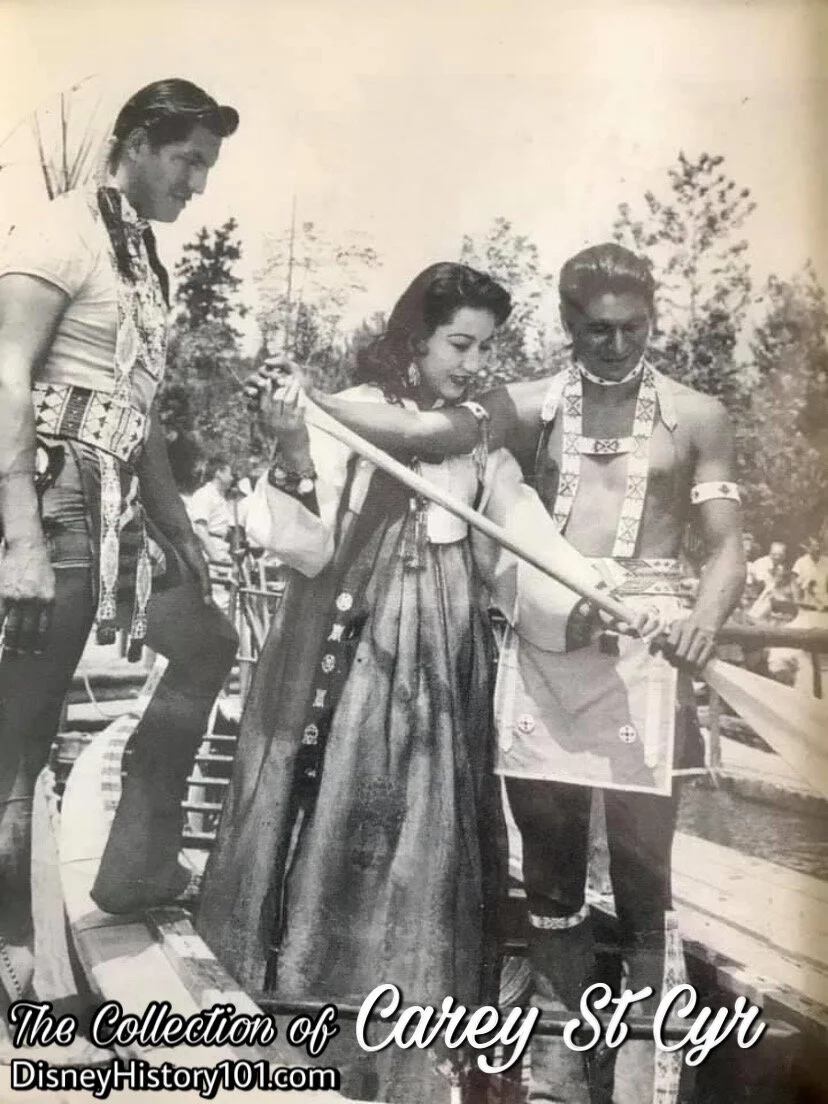

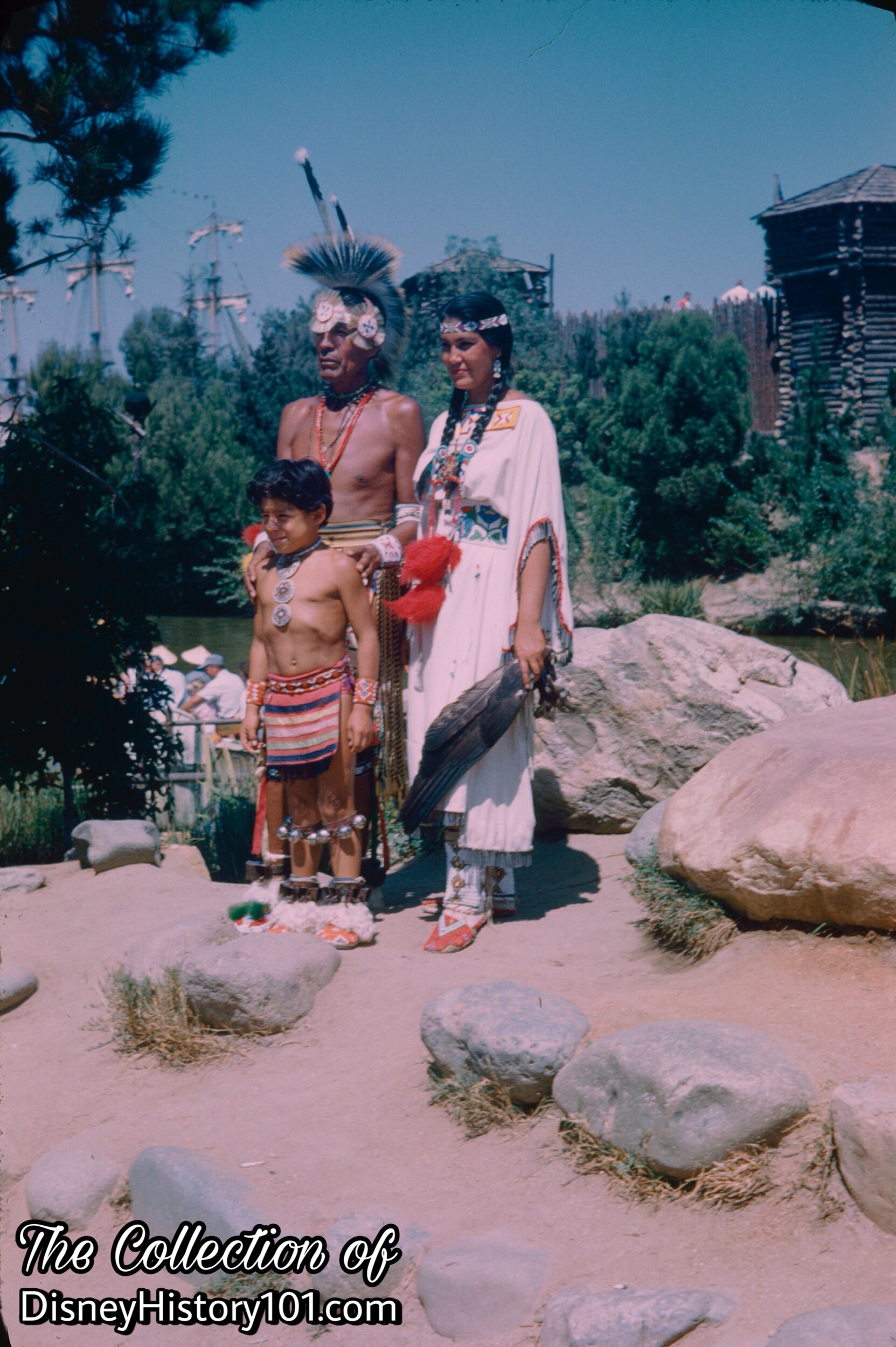

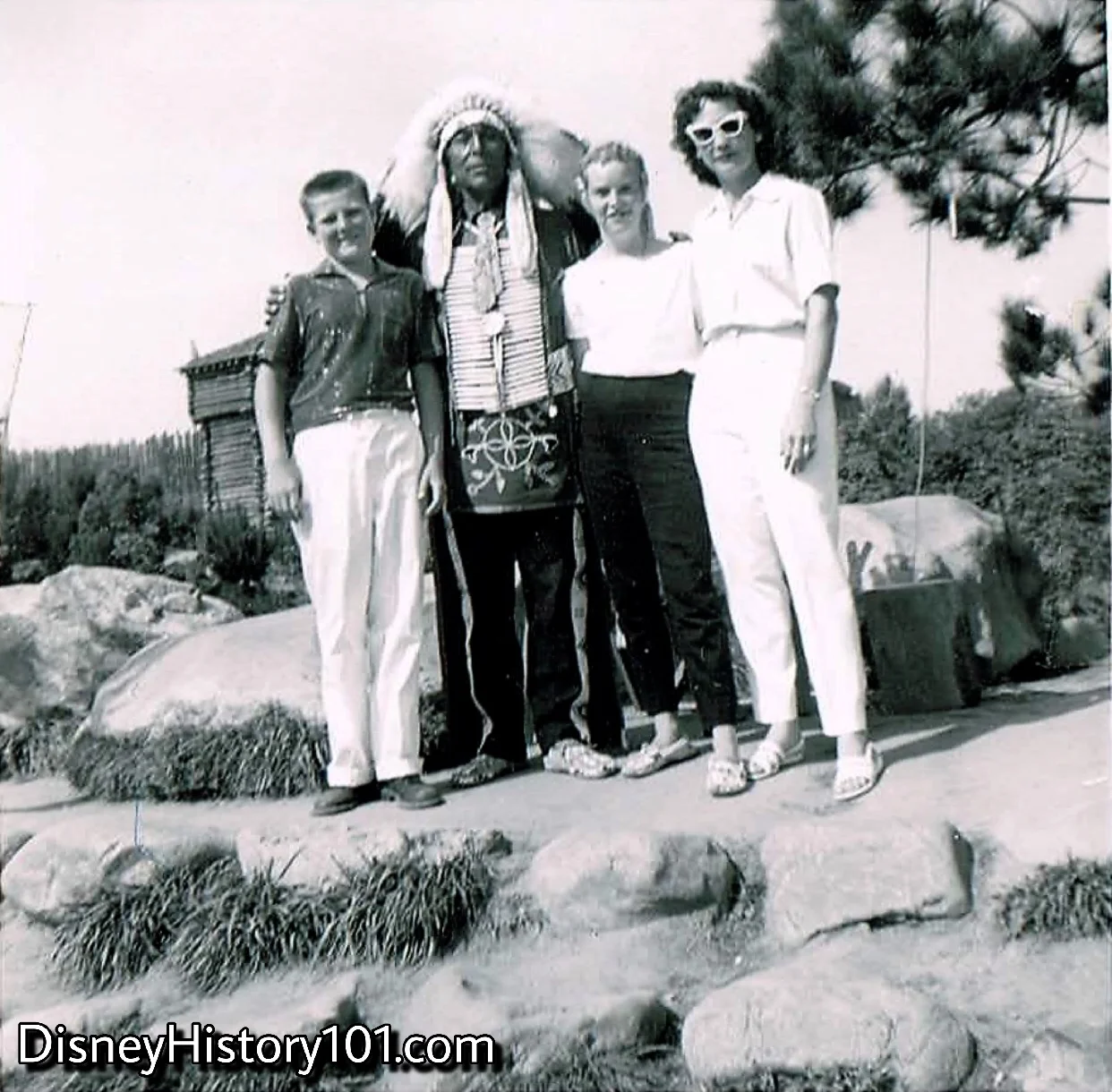

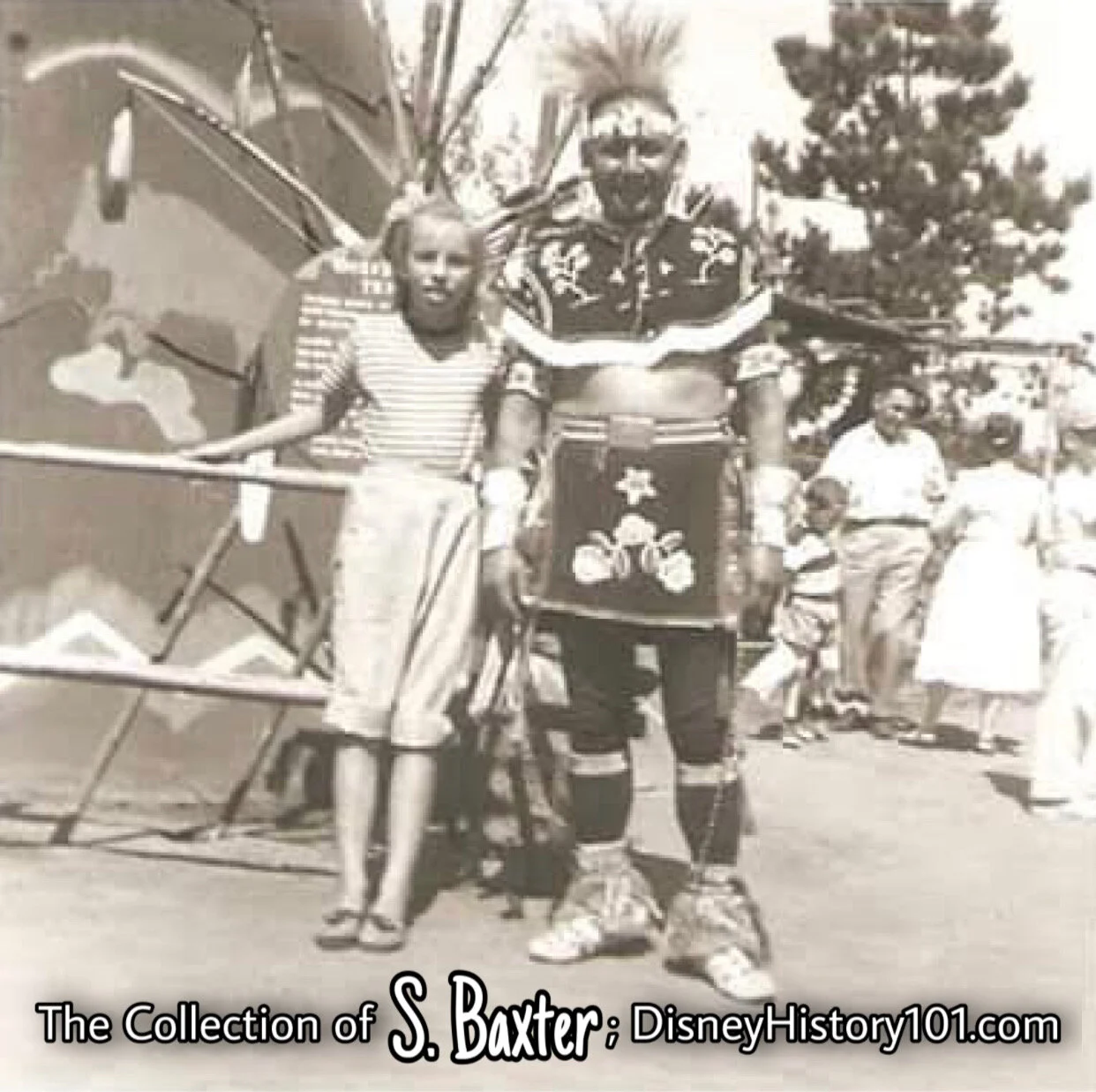

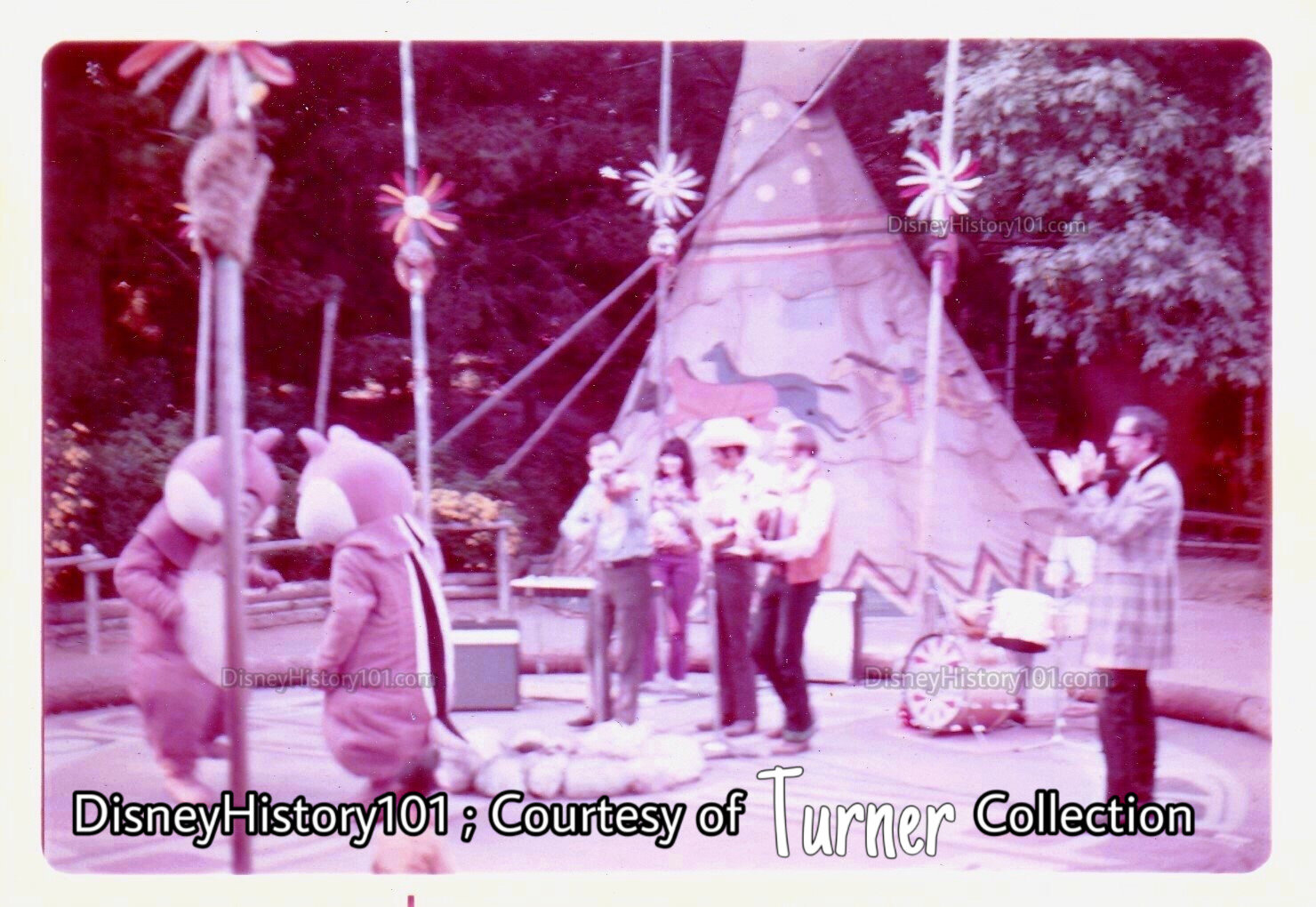

Pictured Above : (left to right) Eddie Little Sky, an unidentified performer, and Louis Heminger

“A Very Important Message”

Before we begin, we must state that the purpose of this gallery is the preservation of historical information as it relates to the diverse people, places, and artifacts that have played an important role in the history of Disneyland. This being the case, there may be some outdated and negative cultural references which some may find offensive, connected with some of the artifacts contained in the following section. Please know that our historians and museum curators do not share some of the expressed archaic views which may be offensive.

Not withstanding this, it has been said that “the past is prologue,” and we believe it is important to educate ourselves about the past, discuss things, and understand changes that have occurred over the years. We also believe that the stories of every individual (no matter how minor their role), have the capacity to both inspire and edify their contemporaries as well as future generations to come. Now, we invite you to step this way, as we explore the story of the Disneyland Indian Village!

“Blue Sky For The Indian Village”

Regarding most any project pursued, Walt Disney once said: “We have always tried to be guided by the basic idea that, in the discovery of knowledge, there is great entertainment as, conversely, in all good entertainment there is always some grain of wisdom, humanity, or enlightenment to be gained.” While it may seem that some current Disneyland attractions don’t embody the full spirit of those words, the story was far different in the beginning. During the first ten years, many entertaining Disneyland exhibits and shows offered more than a shred of “knowledge” or “wisdom.” Some even offered “humanity… [and] enlightenment to be gained” like the “great entertainment” found within the Disneyland Indian Village.

Much like the Riverboat and the Merry-Go-Round, the very idea of an Indian Village has been a part of Walt’s earliest plans for a Park. On August 31, 1948, an important document was circulated among artists of the Walt Disney Studios, in which an Indian Village is mentioned. The Indian Village concept continued to appear in artwork. One of Harper Goff’s c.1951 drawings of “Mickey Mouse Mark” (to be constructed along Riverside Drive in Burbank), depicted an “Indian Village” near the railroad tracks, on the east side of the Park map. Subsequent site plans continued to feature an Indian Village (where potential live shows would be viewable from trains passing over the railroad tracks).

“Disneyland Preliminary Scheme #1”

While many artists contributed, the talented Herbert Ryman is of note. Herb had joined the Disney Studio in 1938, after Walt saw a public show of his work in New York. (Herb's paintings were being exhibited with those of another up and coming artist, Andrew Wyeth.) Herb Ryman acted as art director for such films as Fantasia and Dumbo, but had left Walt Disney Studios in 1946 and (by 1953) was employed by 20th Century Fox. However, Walt reached out to Herb and during one weekend (September 26 & 27, 1953) a historic drawing of the Park was produced.

Herb Ryman subsequently created a colored pencil on photostat concept referred to as “Frontier Land Overall” featuring Native American peoples cooking and crafting near the blockade tower of the entrance. Less than a year later, “The Disneyland Story” of 1954, described the introduction to Frontierland (including a description of Herb’s artwork) - “In front of the fort you will see Indian teepees and Indians selling pottery, jewelry, and souvenirs.” A little later (during November of 1954), an article in The Pittsburgher periodical described the soon-to-be-completed Disneyland as “an entertainment wonderland which will be ‘a combination of a World’s Fair, a playground, a community center, a museum of living facts and a showplace of beauty and magic.’” Those expressions in Disneyland’s core mission statement influenced the development of Sam McKim’s original drawings into the Indian Village.

Disneyland LIFE Magazine c. 1955 Pictorial Photo (by Loomis Dean or Allan Grant) Excerpt Featuring Faux Indians - Mostly Walt Disney Studio Artists.

“The Not-So-‘True-LIFE’ Magazine Photo”

As construction progressed toward opening day, a LIFE pictorial photoshoot was planned, in which Walt Disney’s Disneyland would be introduced to the world. Press release documents (prepared by the Disneyland, Inc. Public Relations Department) promised a Cast of Indians “weaving blankets and baskets” and “selling pottery, jewelry, and souvenirs.”But at this time, Walt and company did not have enough time to assemble a cast of true-life Indian representatives for Loomis Dean’s LIFE pictorial photoshoot. So, some of the Walt Disney Studio workers did something that would be unthinkable by today’s standards (considering modern views of cultural appropriation). They donned some of the traditional clothing and stood along the hills of Frontierland, while a Buckboard wagon passed along a trail, for a one-page picture appearing in LIFE (August 15, 1955).

Acres of Fun Disneyland souvenir fan featured the LIFE Magazine Pictorial photo, c.1955-1956.

Some of these viable project Concepts (as this), were supported by a well-developed business case and built expectation.

Still, this was not Walt’s vision for the Indian Village at Disneyland. Not withstanding the LIFE Magazine photoshoot, Walt (and company) always recognized that casting was essential to the success of any story being told whether in feature-length and short film format, or at Walt Disney’s Disneyland. It would be (and continue to be) the people that are so essential to making the dream of Disneyland a reality! In dedicating Frontierland, Walt Disney said, “all of us have cause to be proud of our country’s history, shaped by the pioneering spirit of our forefathers.” Soon after Walt spoke those words, Disneyland Guests would be “welcomed” to enter “Frontierland near the gates of the old log fort - past leather stockinged frontiersmen and Indians of many tribes, gathered at the entrance.” In what could be considered the first Disney Parks “World Showcase,” Disneyland Guests would soon meet the early peoples that first called America home (rather than just see them depicted on a screen), learn about their diverse cultures, and even have the opportunity to acquire souvenirs of their experience - authentic hand-made arts and crafts! As the narrator of “Disneyland - The Park” (a c. 1957 Disneyland anthology series episode) once said, “such groups [of tribal representatives] help fulfill the purpose for which Frontierland was intentioned - the perpetuation of our country’s heritage.”

The tepees were crafted by Hank Dains of Walt Disney Studios, who worked on Westward Ho! The Wagons. As of June 2, 1955, C.V. Wood Jr. sent an Inter-Office Memorandum to Walt Disney regarding the best estimates that could be obtained at the time regarding the completion status of individual sections of the Park and Opening Day. C.V. wrote: “Tepees: These should be easily completed.”

By Press Preview Day, visitors noted that this exhibit was populated with the True-Life peoples, as did one contributing writer for The Daily Oklahoman.

Despite the preceding lack of true-life Indian talent lined up by 1954, Disneyland visitors would soon be able to experience the sight of select “Ceremonial Dances,” in Walt’s promised “community center” and “museum of living facts.” These “ceremonial dances” would be demonstrated by true-life representatives of different tribes, after an arrangement was reached with the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

As far as these Disneylanders representing both Walt Disney Productions on a person-to-person basis, Walt later expressed the following confidence: “What you do here and how you act is very important to our entire organization and the many famous names of American business represented among our exhibitors… Your every action (and mine also) is a direct reflection of our entire organization… For our guests from around the world the curtain goes up on an all new show at Disneyland everyday and you, as a host or hostess, are truly ‘on stage.’ I know you will give a courteous and friendly performance.”

After applying in 1955, Disneyland Hosts and Hostesses were “hand-picked by Disneyland officials with qualifications including disposition, general attitude and appearance. Each new Disneyland employee was required to attend ‘orientation classes,’ part of a training course in Disneyland policies, to become acquainted with the Disneyland way of life,” according to “Building A Dream,” prepared by Disneyland, Inc. Public Relations Department, c. June of 1955. The orientation classes were administered five months before the premier opening, through Hal Hensley of the Disney University Orientation Program, and under the Direction of Van Arsdale France and his recently hired assistant Dick Nunis. Since the beginning, every Cast Member was taught that they were “a direct, personal representative of Walt Disney and the entire Disney organization.” [“Welcome to Disneyland,” 1981] As such, these classes were intended to instill and maintain the “friendliness, quality and cleanliness” of Disneyland Cast Members and Indian Village representatives included, and to bestow upon each one, the “special ingredient” - magic!

While all Indian Village Cast Members were “hand selected” for employment, only some performers attended Hal Hensley’s orientation classes. For example, special guest Little Sky (the great-great-grandson of the notable 19th century Oglala Leader “Crazy Horse”; whom along with “Sitting Bull” led the attack against General Custer at what is called the battle of “Little Big Horn”) was invited to perform on the Grand Opening public day of Disneyland (without having attended the class). According to the accounts of those interviewed, many others were recommended for the position by family members and friends, before being “hand selected” by those in charge of screening the talent.

A press release photo depicts an Indian Village representative greeting stagecoach passengers; ©️Walt Disney Productions.

It was on July 17th, 1955, that these “hand selected” First Peoples and Disneyland representatives made history, as they proudly marched in the Indian Unit (of the Frontierland Section) of the Disneyland Press Preview Day Parade. Images have been preserved in print as seen in "Homecoming - Destination Disneyland" by Carlene Thie with photos by Mel Kilpatrick. While tipis appeared along the entrance to the Stage Coach Trail that day, it wasn’t until the following morning (of Monday, July 18th, 1955), that the Indian Village first opened near Adventureland, as the “American Indian Village”! Little Sky (of the Oglala-Lakota) and others performed demonstrations of ceremonial dances, from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Photographs were usually welcome by Indian Village Cast Members (and visitors took advantage of this kind opportunity on this occasion). Owing much to photographs that were permitted (and especially the recollections of the individuals involved), this culturally significant section of Frontierland lives on right here at Disney History 101. So, we invite you to please step this way as we explore The Indian Village!

Bridge to the "American Indian Village," the banner out of frame to the left.

Souvenir guides to Disneyland advertised: “Frontierland is where you'll actually ‘live’ America's colorful and historic past. You enter Frontierland through the gates of an old log fort - past leather stockinged frontiersmen and Indians of many tribes, gathered at the entrance.”

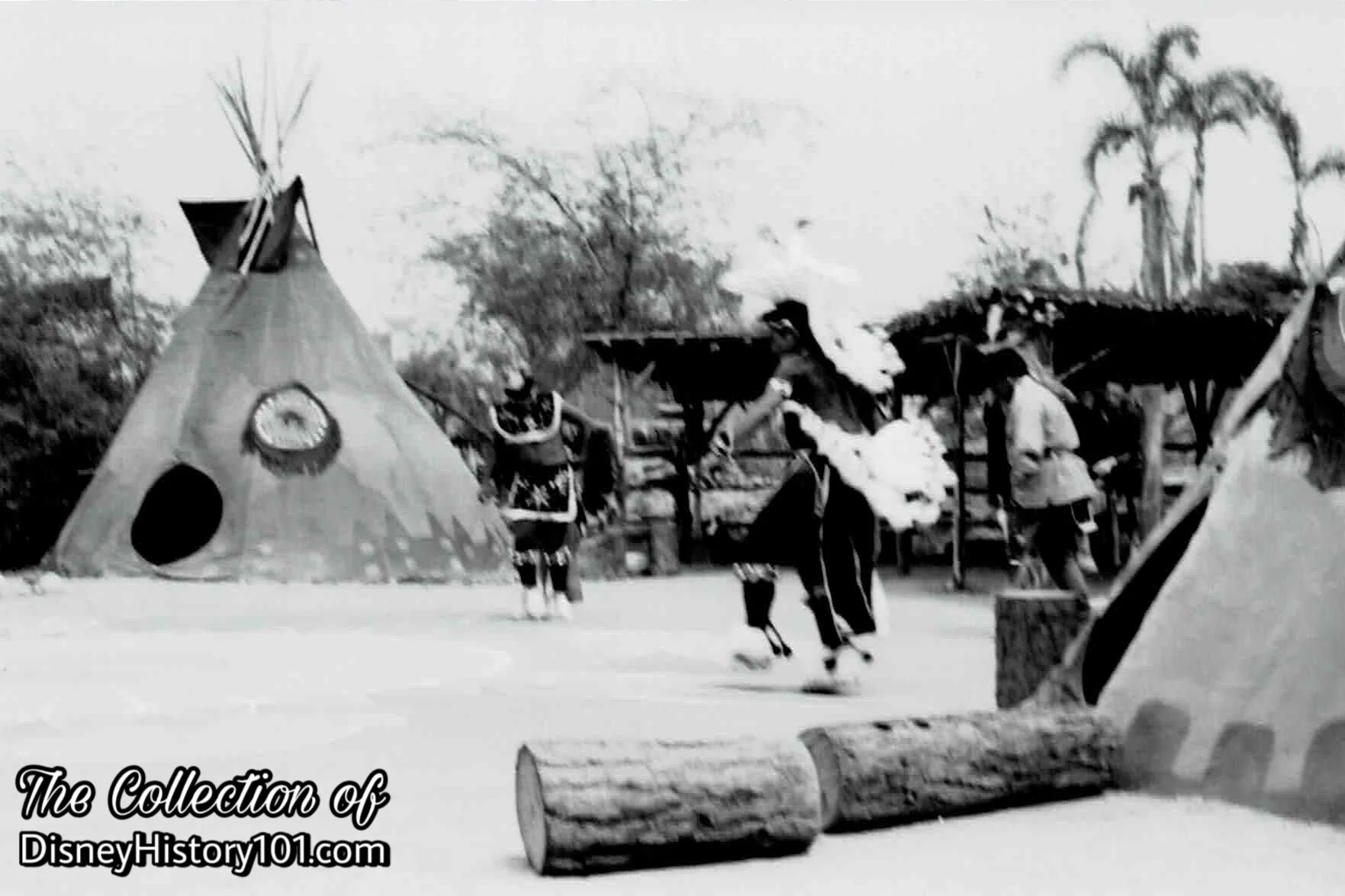

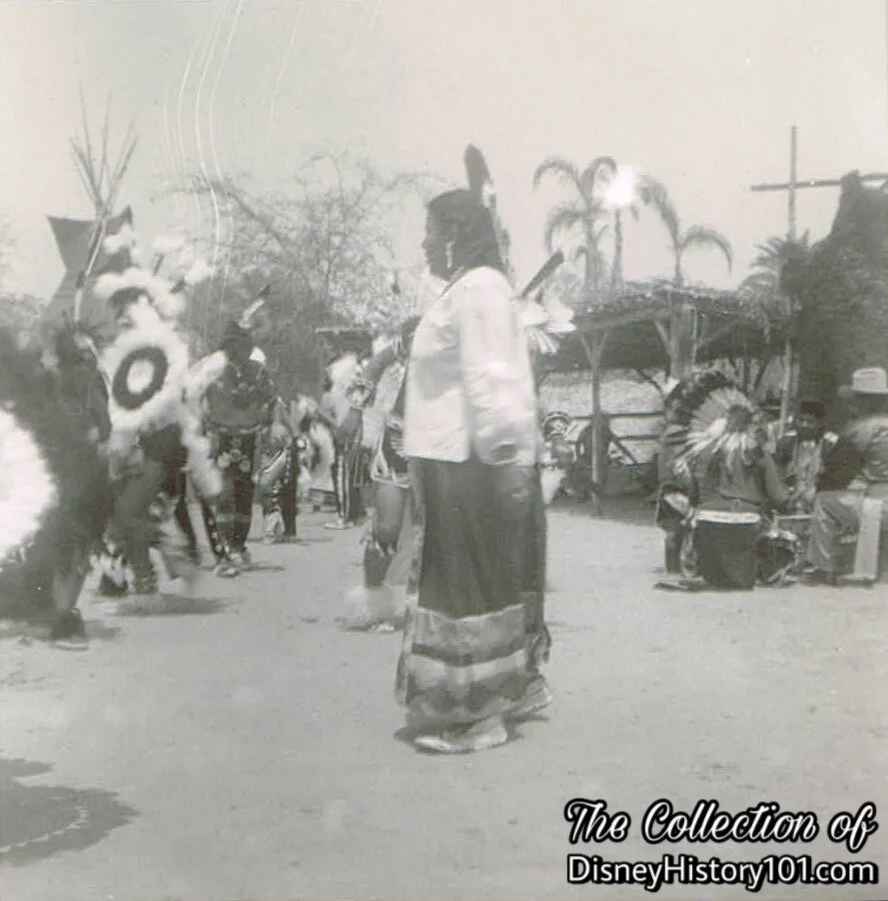

It may surprise you to find that the original “American Indian Village” (as labeled on 1955 banners), was not located in Frontierland, but next to the Jungle River Cruise, in a small section of Adventureland. As you look over the next few “Vintage Views,” notice the tropical palm trees on the other side of the berm, in the background that attest to its location.

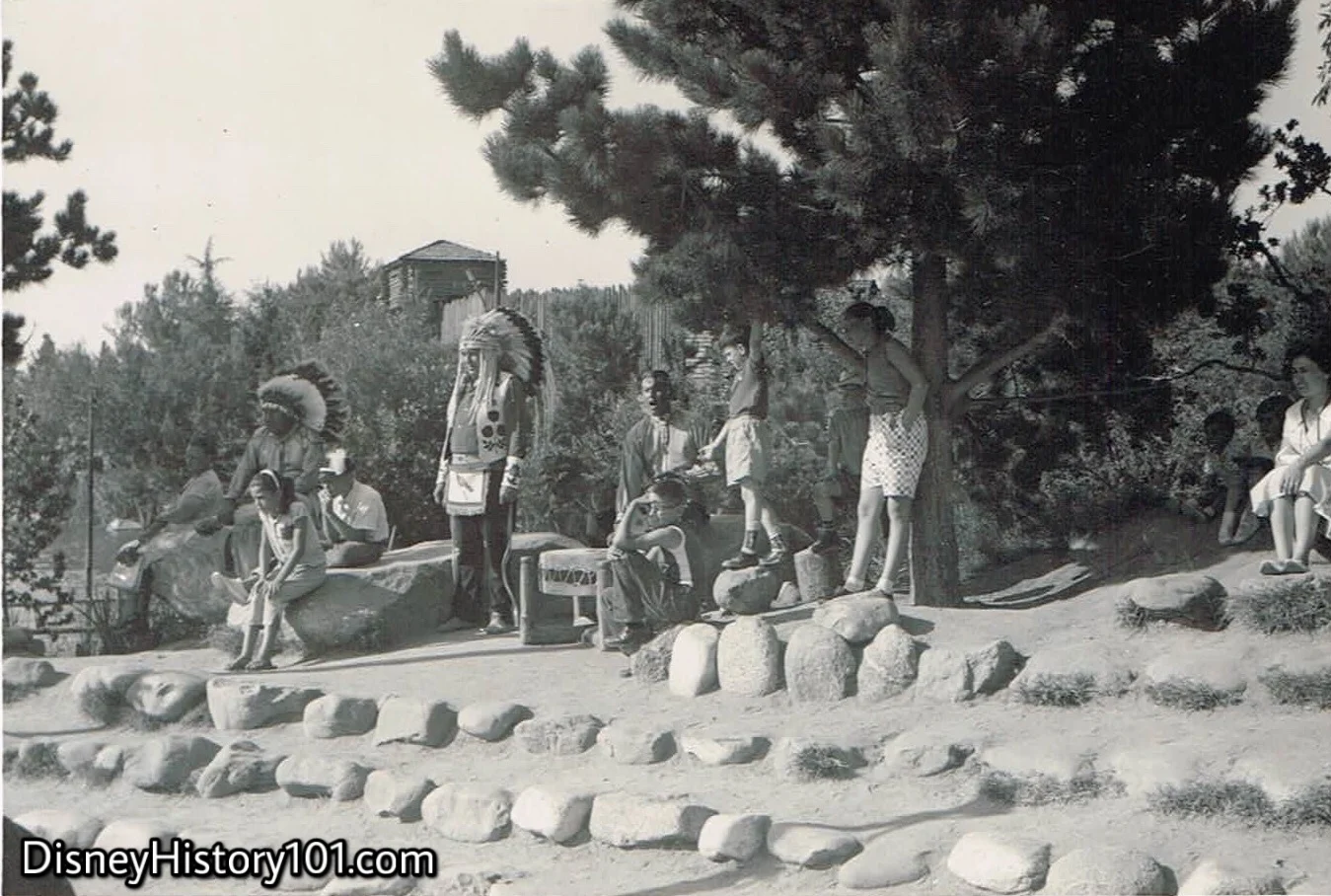

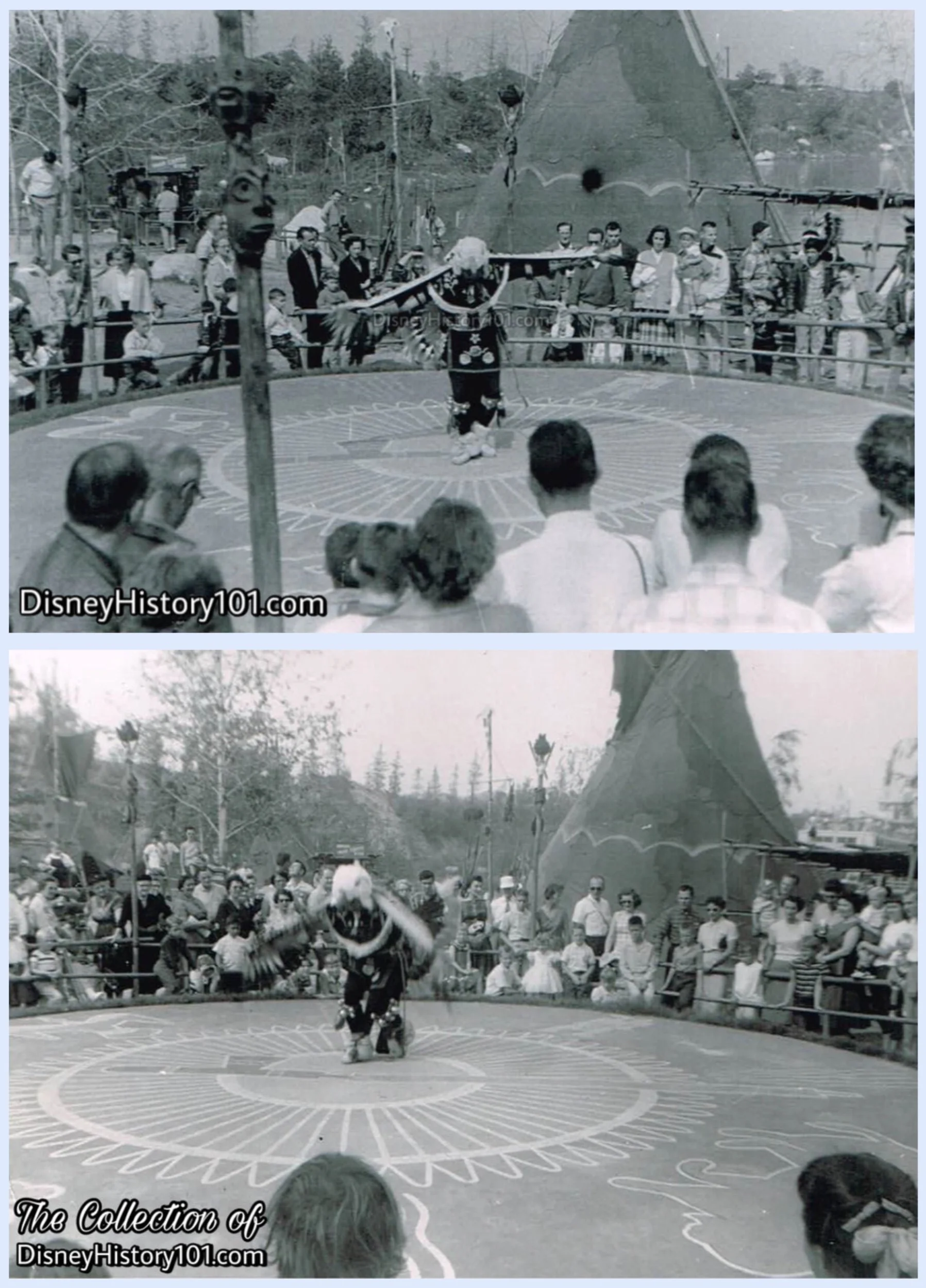

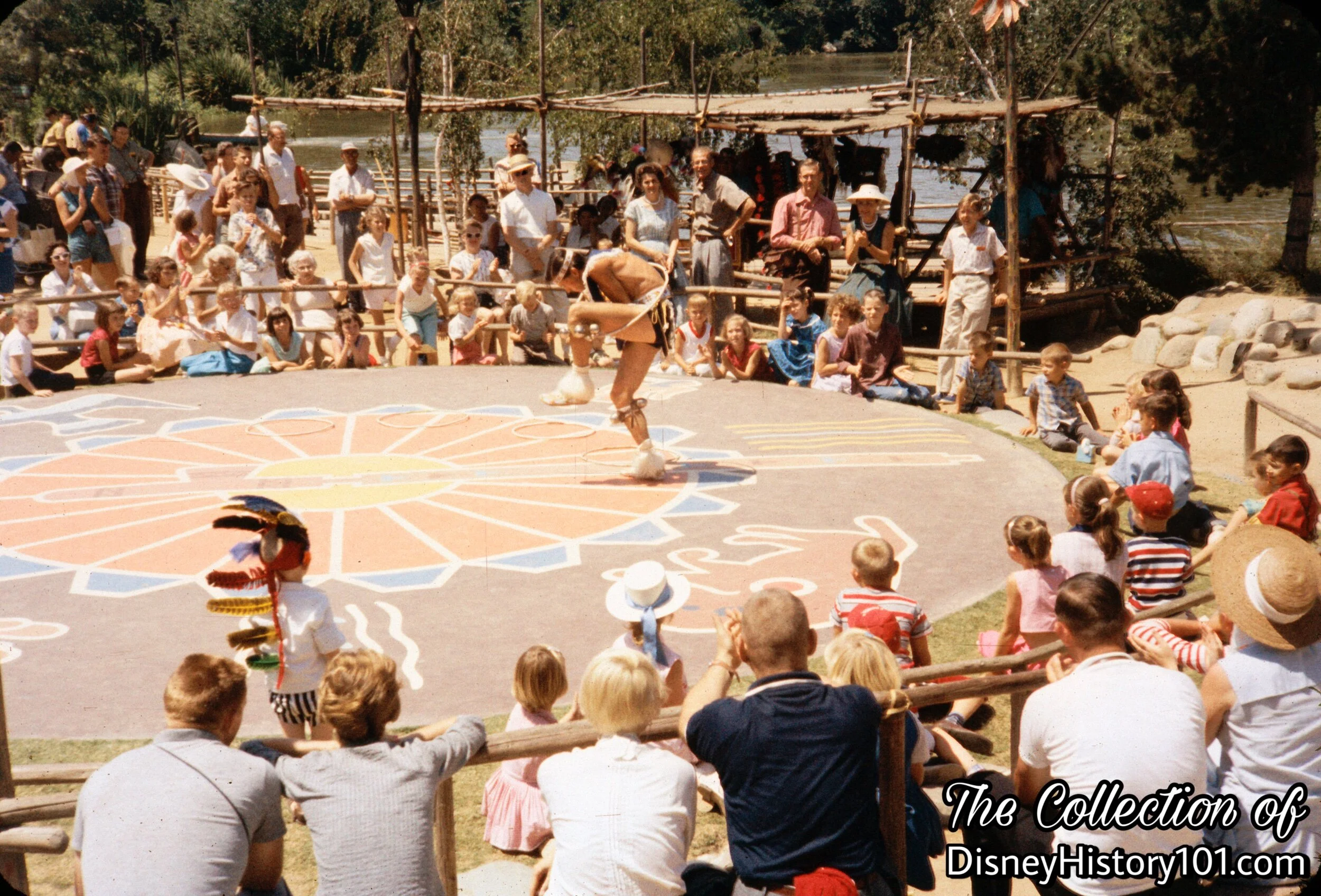

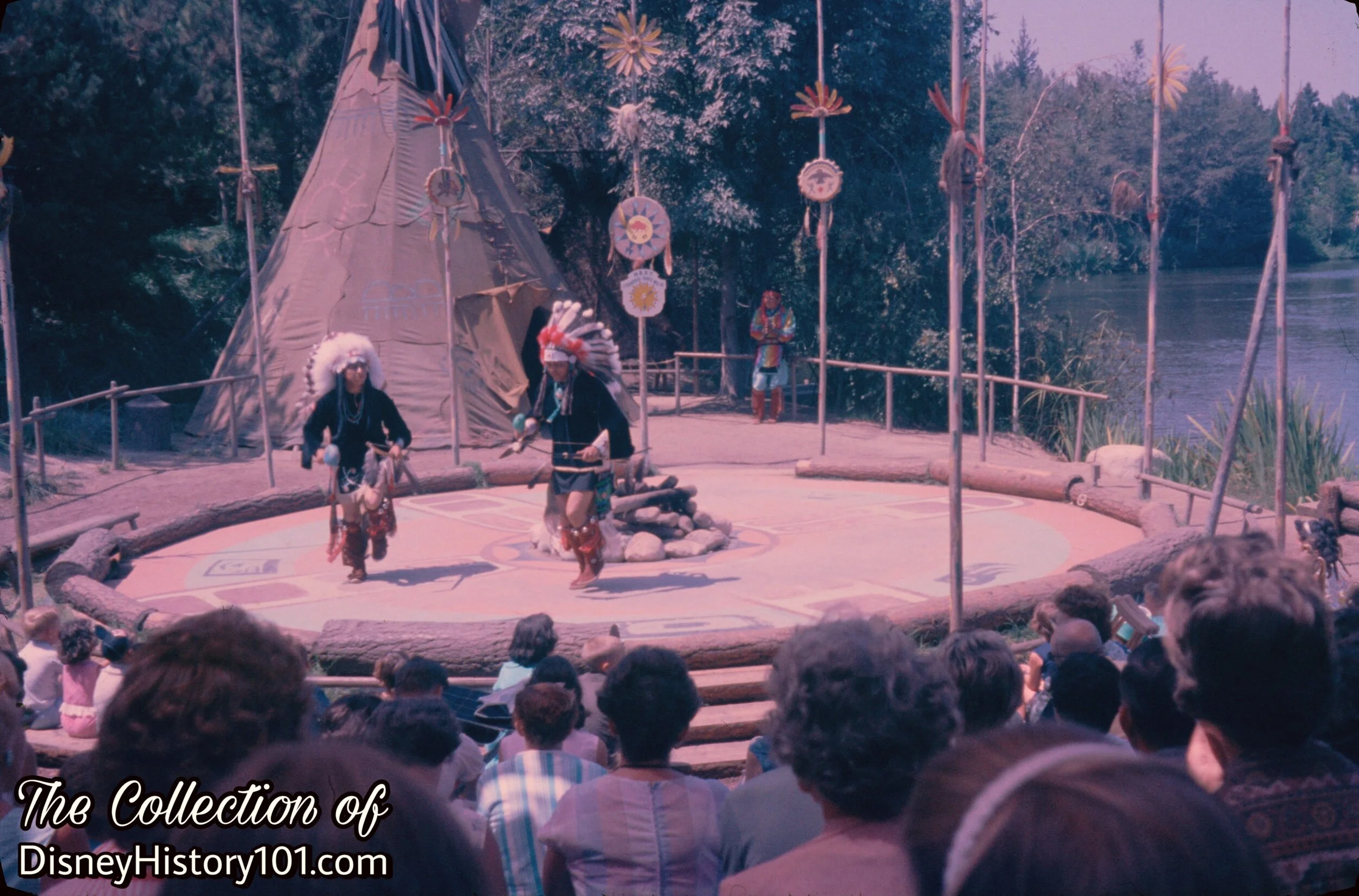

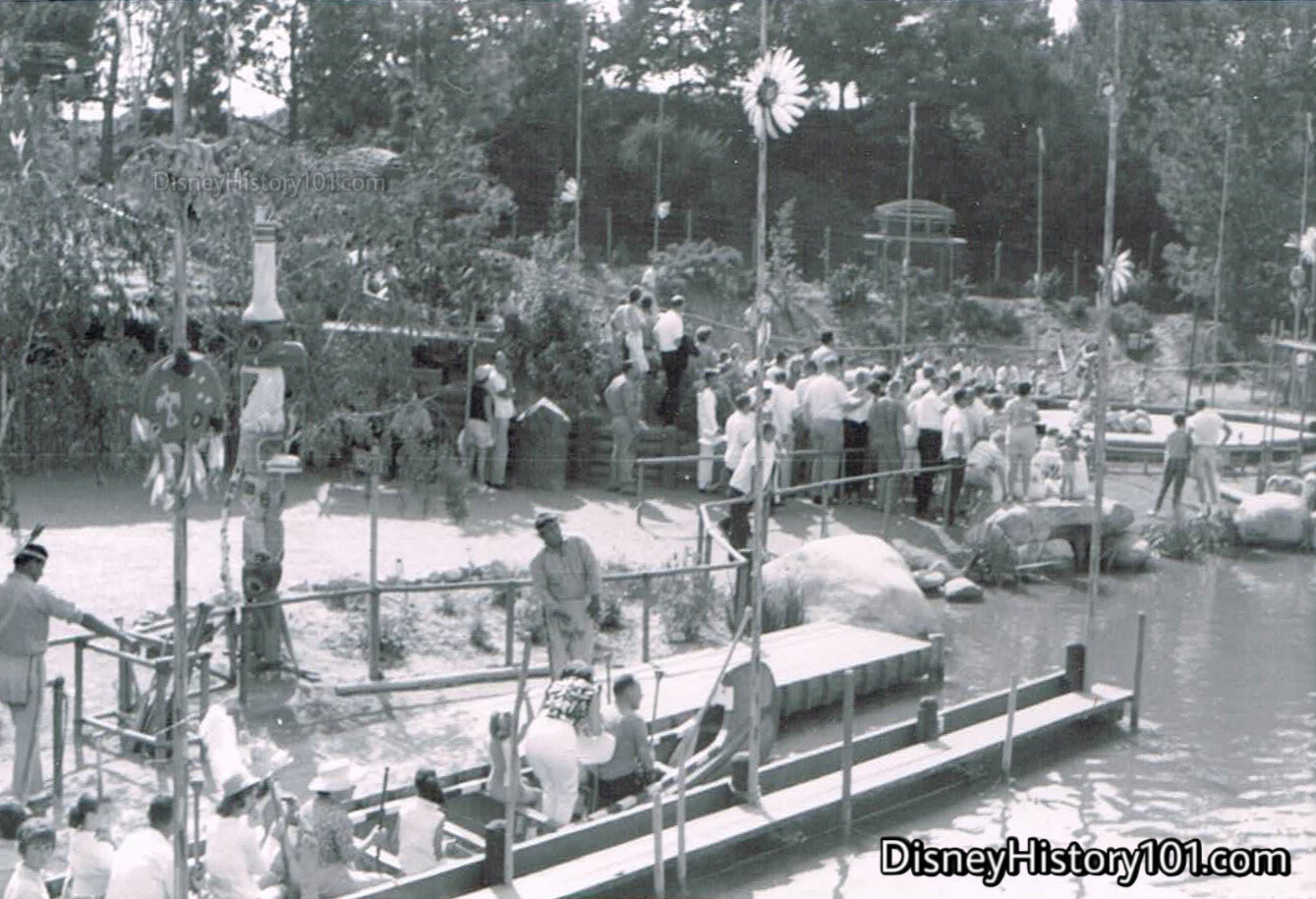

The original Indian Village Ceremonial Dance Circle, (September, 1955)

“Good afternoon friends, Welcome to The Indian Village.”

-Truman “Chief Whitehorse” Daily (1898-1996).

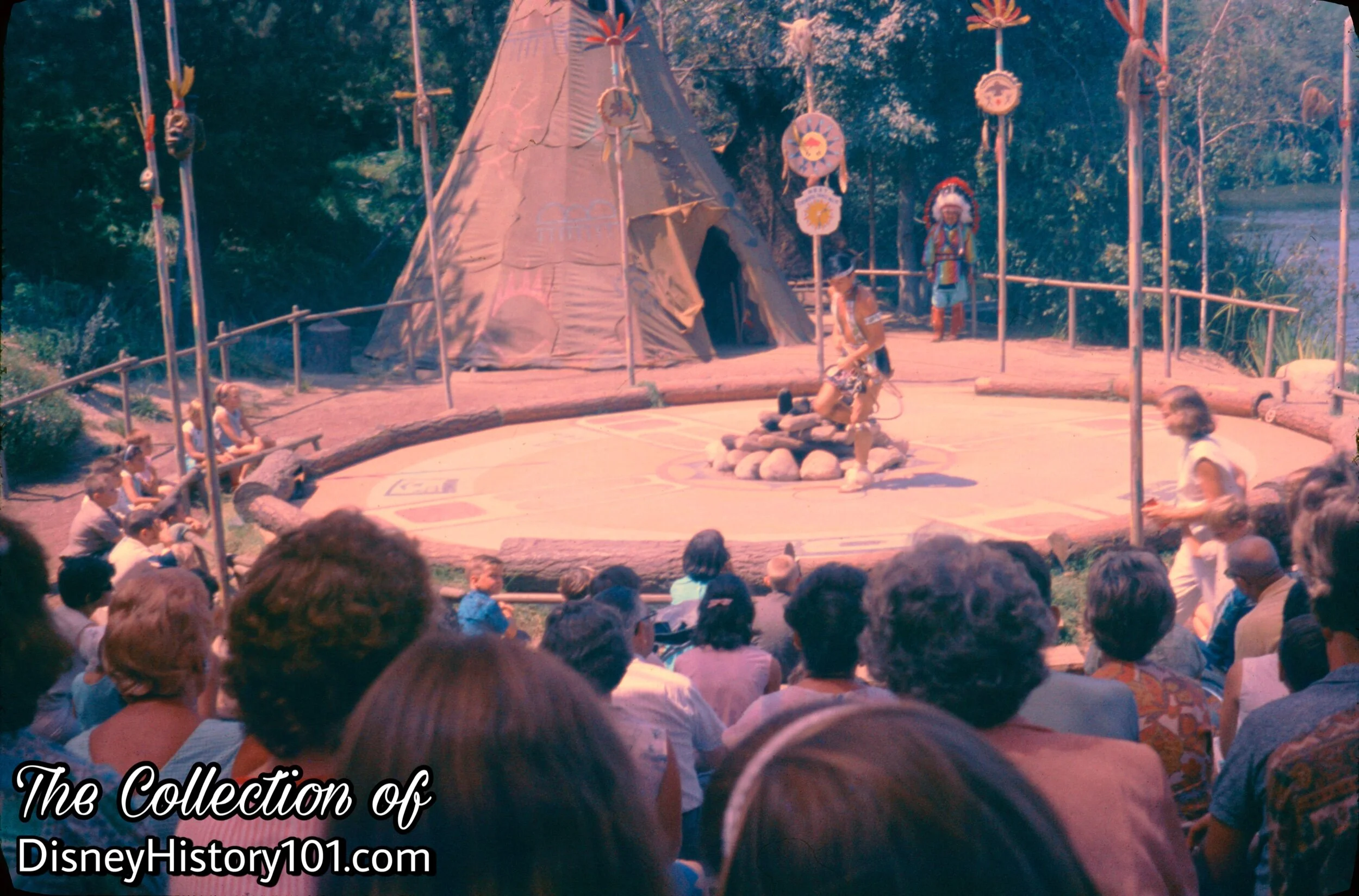

The main attraction of the American Indian Village (or Indian Village), was Ceremonial Dance Circle, where guests were welcomed to watch select “Ceremonial Dances.” In these early days, the “experts on the past” were members of individual troupes (typically composed of a specific tribe), which were brought in to represent their people. Their performances were seasonal - during holidays, summers, and weekends.

I would like to turn your attention to the circular design in the center of the circle, which served as the symbol of the sun, with its life-sustaining rays. Drawing upon references from the Walt Disney Studio Library, Sam McKim designed the eagle, the beaver, the buffalo, and the man, which were painted around the sun, as each of these creatures (“a symbol of wisdom”) benefits from the rays of the sun!

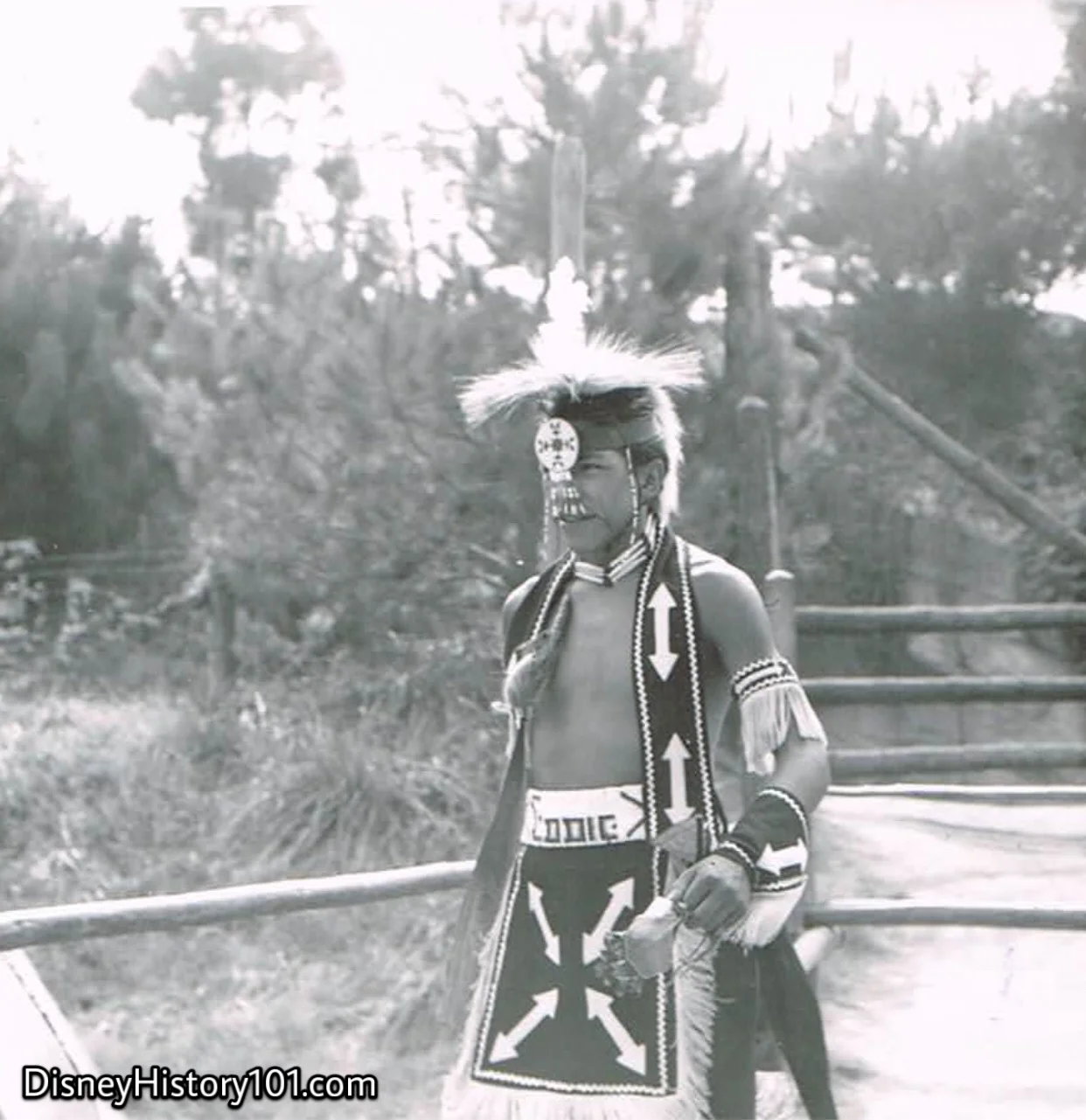

The original Indian Village Ceremonial Dance Circle and Eddie Little Sky (left), (July 1955 - Spring 1956)

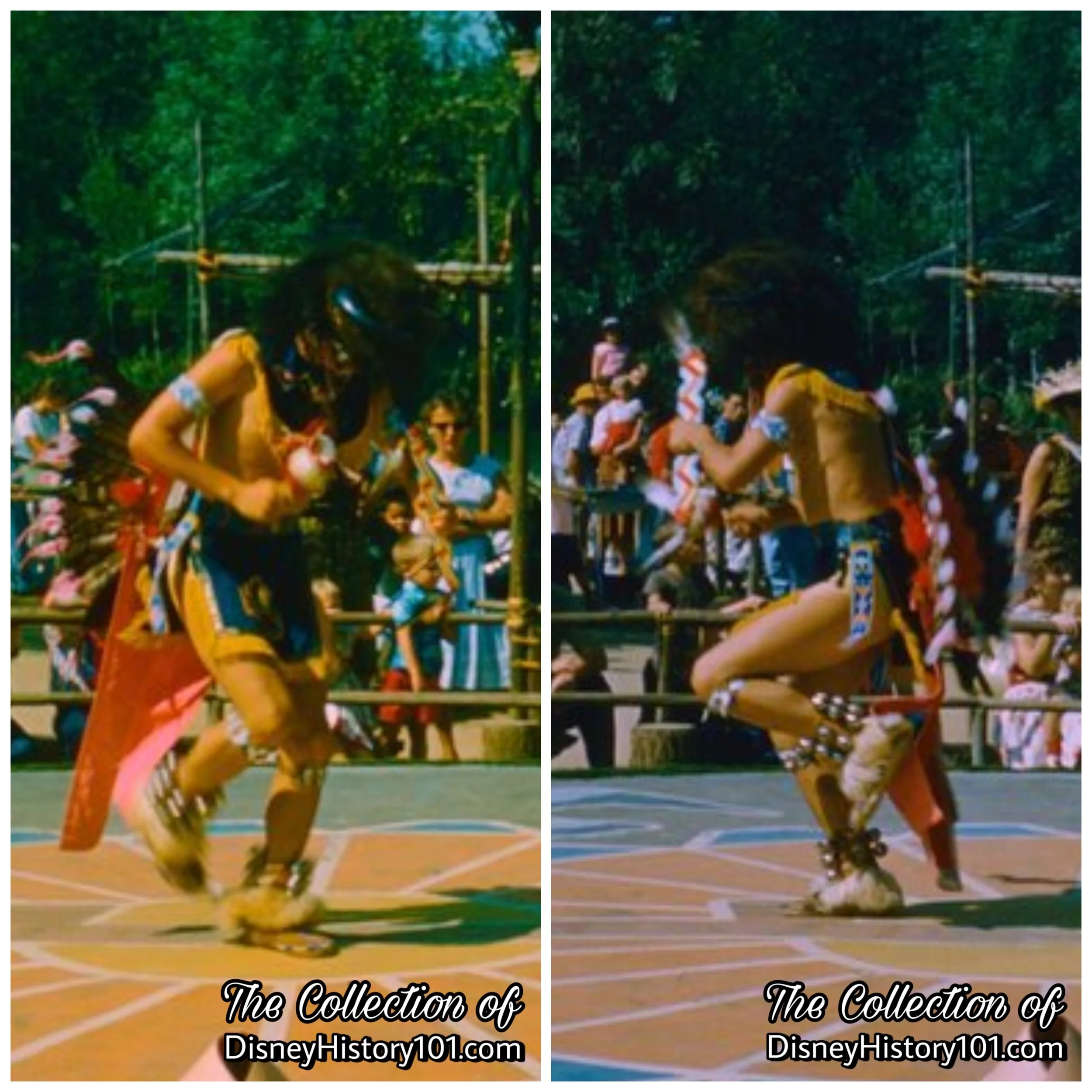

There were authentic Indian performances of both traditional and modern dances. These performers wore traditional tribal reproductions - bustles, breechcloth, roaches, and more!

The original Indian Village Ceremonial Dance Circle and Eddie Little Sky (Right)

Edgar Foster Hood in red with white bustle.

The original Indian Village Ceremonial Dance Circle, (July 1955 - Spring 1956)

The original Indian Village Ceremonial Dance Circle, (July 1955 - Spring 1956)

The original Indian Village Ceremonial Dance Circle, (July 1955 - Spring 1956)

The original Indian Village Ceremonial Dance Circle, (July 1955 - Spring 1956)

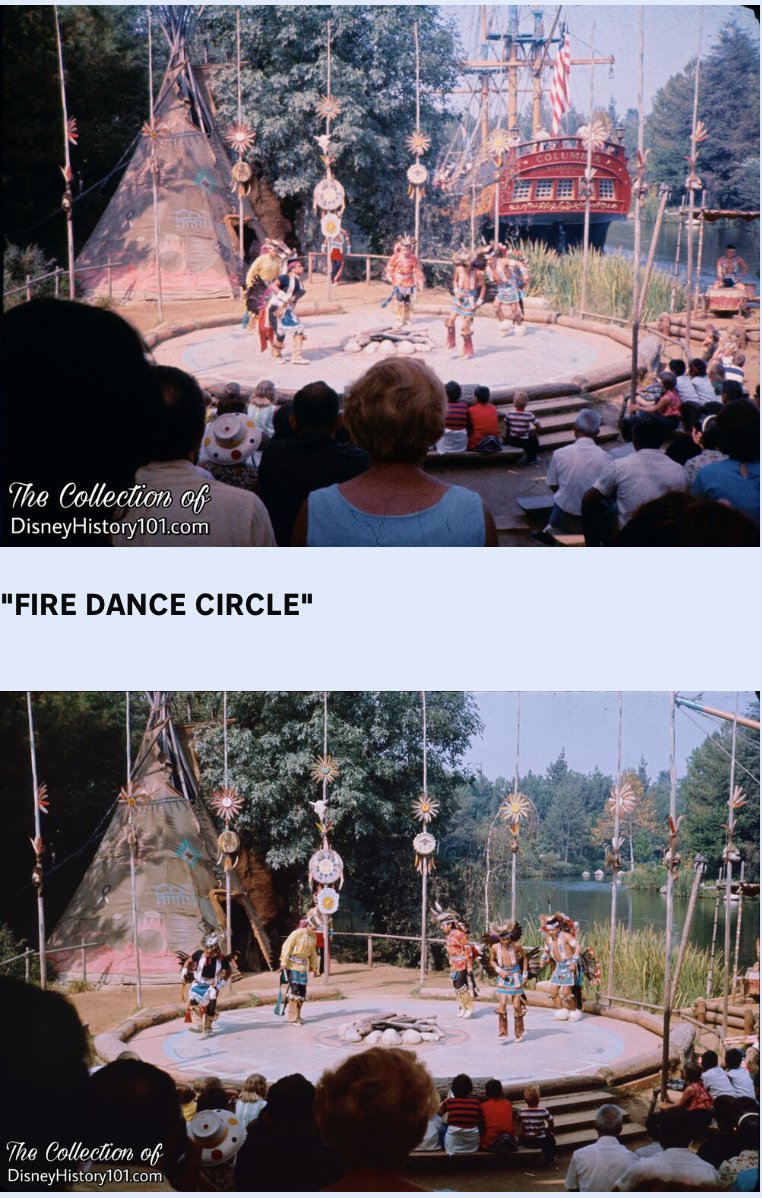

Ceremonial Dance Circle was also called Fire Dance Circle, even in these early days. The small stage was fenced-off and not open to the crowds. Those logs in the foreground were not used for seating, but generating fire. Around the Ceremonial Dance Circle were the four (to five) tipis and wooden awning that comprised the Indian Village - all constructed using techniques passed from generation to generations, and thus as accurate as can be. Guests could view the outside of the structures, but most of the tipis were lacking the elaborate interior dioramas that would represent various aspects of diverse American Indian lifestyles.

Unidentified Host (left) and Eddie Little Sky with Guest at the original Indian Village Ceremonial Dance Circle

Women of the original Indian Village Ceremonial Dance Circle, (July 1955 - Spring 1956)

Even in the original Disneyland Indian Village, women had a presence in demonstrations, and though men performed most of the dances, women were heavily involved in the diverse tribal craft demonstrations performed for Guests.

Women of the original Indian Village Ceremonial Dance Circle, (July 1955 - Spring 1956)

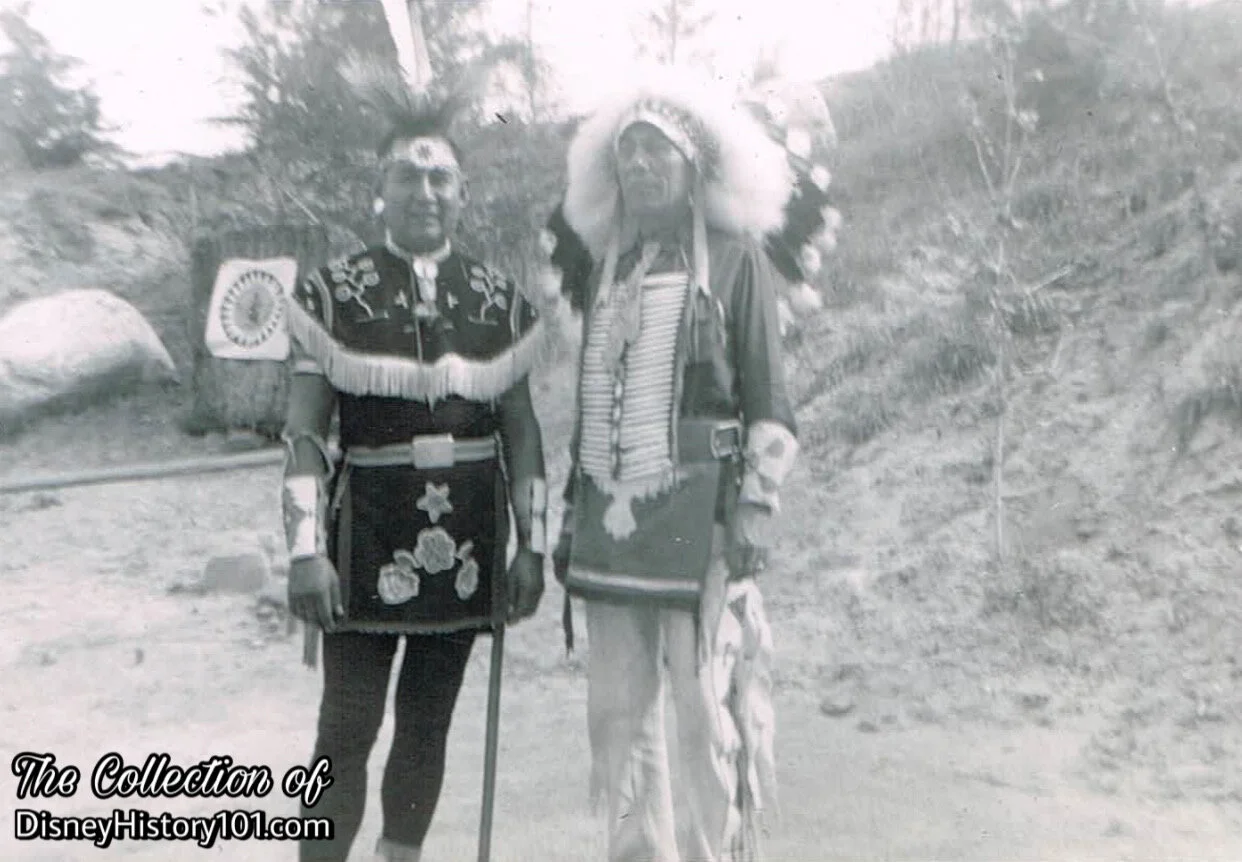

Louis Heminger - "Chief Shooting Star" (right), and unamed Disneylander (left) at the original Indian Village Ceremonial Dance Circle

Both were so prominently active at Disneyland’s Indian Village during its early era, that both were photographed welcoming Disneyland’s 10 millionth guest (five-year-old Leigh Woolfenden) when she visited Disneyland with her family on December 31, 1958 [see Disneyland Holiday magazine, Spring 1958, page 1]!

While the representative known as Chief Red Feather of the Navajo-Sioux greeted guests at Knotts Berry Farm, Louis Heminger of the Dakota Sioux (pictured right), was best known to Disneyland guests by his Sioux-bestowed “honorary“ title Chief Shooting Star. He prominently led the festivities and demonstrations of (mostly Plains) Indian cultural dances for three years, within Disneyland’s Indian Village. Louis also became the representative “face” of Disneyland’s Indian Village and Frontierland, to the point where he was featured in many early publications (like Walt Disney’s Guide to Disneyland, published 1958, and Walt Disney’s Disneyland, a Giant Tell-A-Tale book, published in 1964 by Whitman). Chief Shooting Star welcomed actress Spring Byington (of “December Bride) and child actor Bobby Diamond (of “Fury”) to the Disneyland Indian Village for their 1956 “TV Radio Mirror” photoshoot at Disneyland! Chief Shooting Star (along with Disneyland Director of Customer Relations, Jack Sayers) also helped to welcome Disneyland’s One-Millionth visitor Elsa Bertha Marquez from the steps of Disneyland City Hall, on September 8th, 1955. In these early days, Louis Heminger was joined in Disneyland’s Indian Village, by Lee High Sky (of the Shawnee), Little Arrow (of the Winnebago), Eddie Little Sky (of the Sioux), and a few other representatives of America’s true natives!

Louis Heminger - "Chief Shooting Star" (right), Eddie Little Sky (left), (August, 1955)

“Here, Age Relives Fond Memories of the Past”

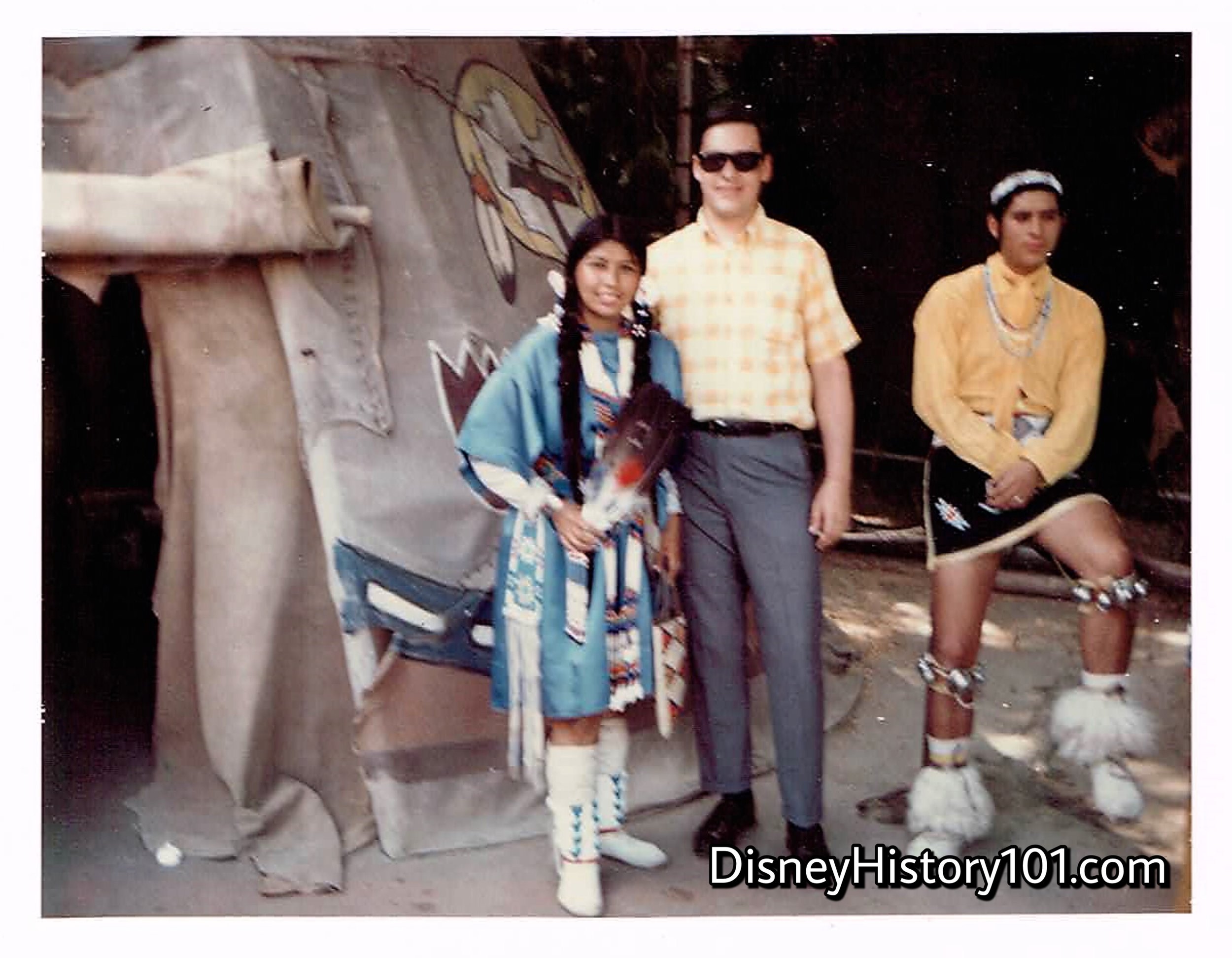

Since the beginning, Atmosphere Entertainment complimenting the theme of areas is staged to entertain Disneyland Guests on an immediate and personal level. By 1956, representatives (or, “ambassadors”) of the Caddo Nation, Sioux Nation, Cheyenne Nation, the Shawnee Tribe, and Ponca Nation were well represented, enhancing the quality of the Disneyland Show. For example, one female performer (Shirley Lovell), was of Cherokee, Apache, and Navajo descent, capable of sharing cultural experiences from those peoples. This was a place where Indians could unitedly share select stories from their cultures with guests, and among themselves. Here, we can see Sioux Chief Shooting Star (right) and his friends interacting with guests.

That the interaction between guests and performers was meaningful, is evident through the sentiments of visitors like Pat (whose father was of the Wichita, and grandparents were of the Caddo). She later recollected in and interview : “I came out from Oklahoma in 1950, and I was very lonely because I did not know that there were native Americans in California,…and I found Native American people in Disneyland. So I would come to Disneyland to talk with them, and I felt happy when I talked with them, because I felt a kinship with them. They shared their feelings as well, and it was a short talk because they had to get back to work. It was good. Each time I was able to speak to a different Native American, they belonged to tribes I was not familiar with. But I still felt a kinship to them because they were Native American. I often went back to Disneyland just to feel at home with Native Americans.” (Collection of Ross Plesset)

During the first winter season an article was published in The Disneyland News during December of 1955: “DISNEYLAND'S CHIEF SHOOTING STAR was on hand to welcome the visiting Russian journalists who stopped off at Disneyland and their four of the United States. Valentin Berezhkov, Viktor Poltoratski and Anatoli Sofronov found the Chief's explanations of his tribe's traditions and instructive bit of Americana.”

Louis Heminger - "Chief Shooting Star," (1955 - 1956)

Walt Disney tours the original Indian Village, (October 26, 1955)

Speaking of ambassadors, Walt Disney (the first Cast Member) played the ambassador for (Mumbai) India-born actress Merle Oberon! He was so excited to show off Adventureland’s Indian Village with the representatives of “First People” American culture to his guests!

As a side note, the Disneys would become good friends with Merle and her husband Bruno Pagliai, after the two were married in 1957. Walt and Lillian even spent a holiday with Merle and Bruno, while visiting Mexico during 1964. During November of 1964, Walt extended an invitation to Merle, Bruno and their children, to view the Disneyland Christmas Parade as their guests. Walt even invited their children to ride with him in the parade. We’ll tell that story another time, and return to the main attraction.

Walt Disney tours the original Indian Village, (October 26, 1955)

As Walt scuttles away to show off another of his new attractions, big changes are swiftly heading toward the humble Indian Village!

(Previous Vintage View Date : July 7, 1956)

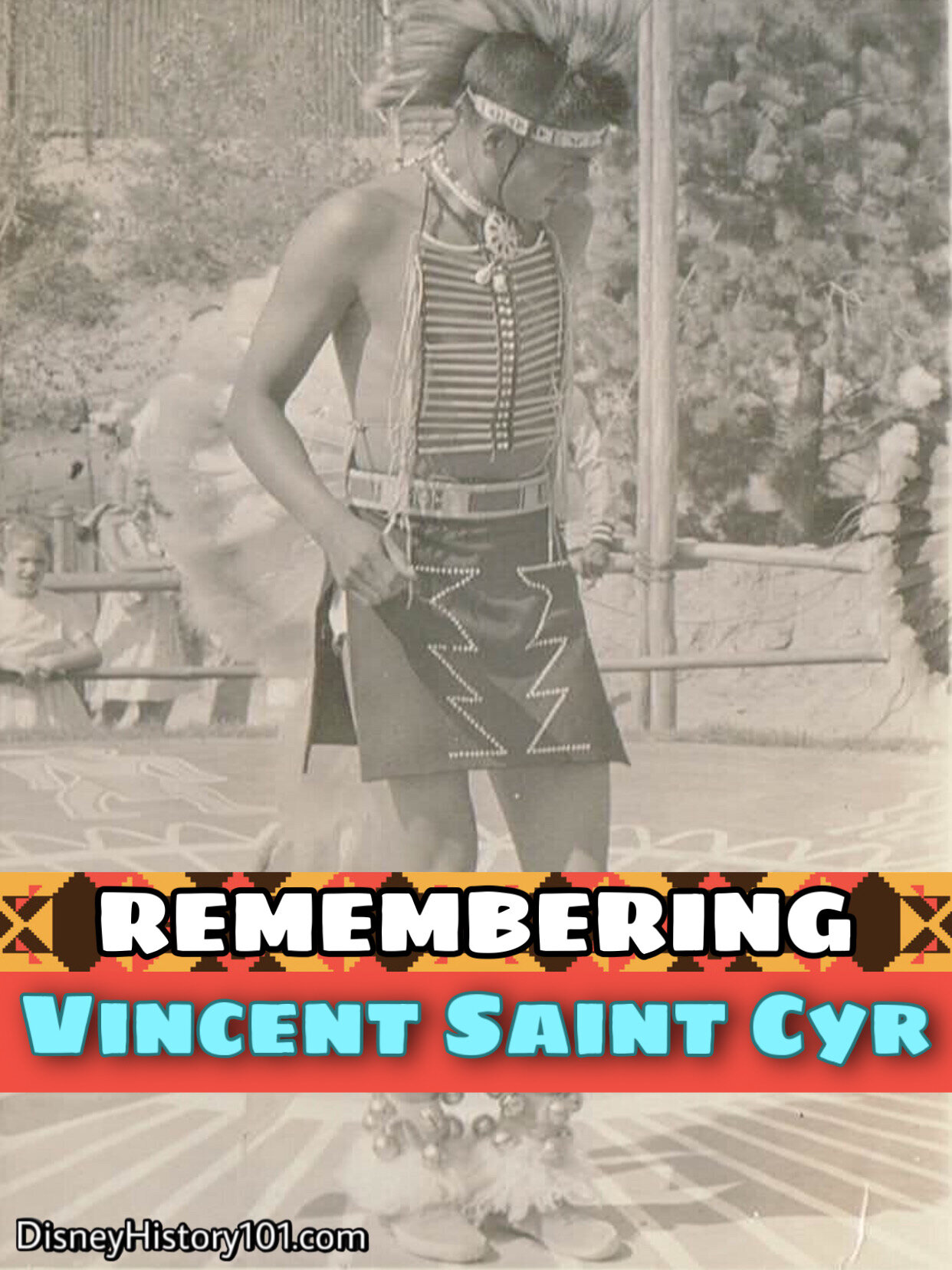

The Magic of Disneyland began with individual Cast Members like Vincent Saint Cyr of the Winnebago Tribe. In an EXCLUSIVE with Disney History 101, “Carey Saint Cyr Remembers His Father - Vincent Saint Cyr.”

“My dad!…His hair was short then. I believe it was growing out from being shaved for a movie called ‘Comanche Station’ starring Randolph Scott.

I recognize parts of his costume. The breast piece, or ribs, was a kind of rudimentary body armor. The bells, of coarse, are used to keep in time with the drum. The [bead]work he wears, is all handmade, signifies designs of his clan and family history.

I do remember the design on the cloth . . . I think I recall the design being made from small shells. Other than a design adornment, I can not recall the significance of the design. I don’t recall a significant meaning for the choker bead work as well. I remember when my mom and dad used to do beadwork at the kitchen table as a child. I always thought there was a kind of magic when I saw the results over days and weeks.”

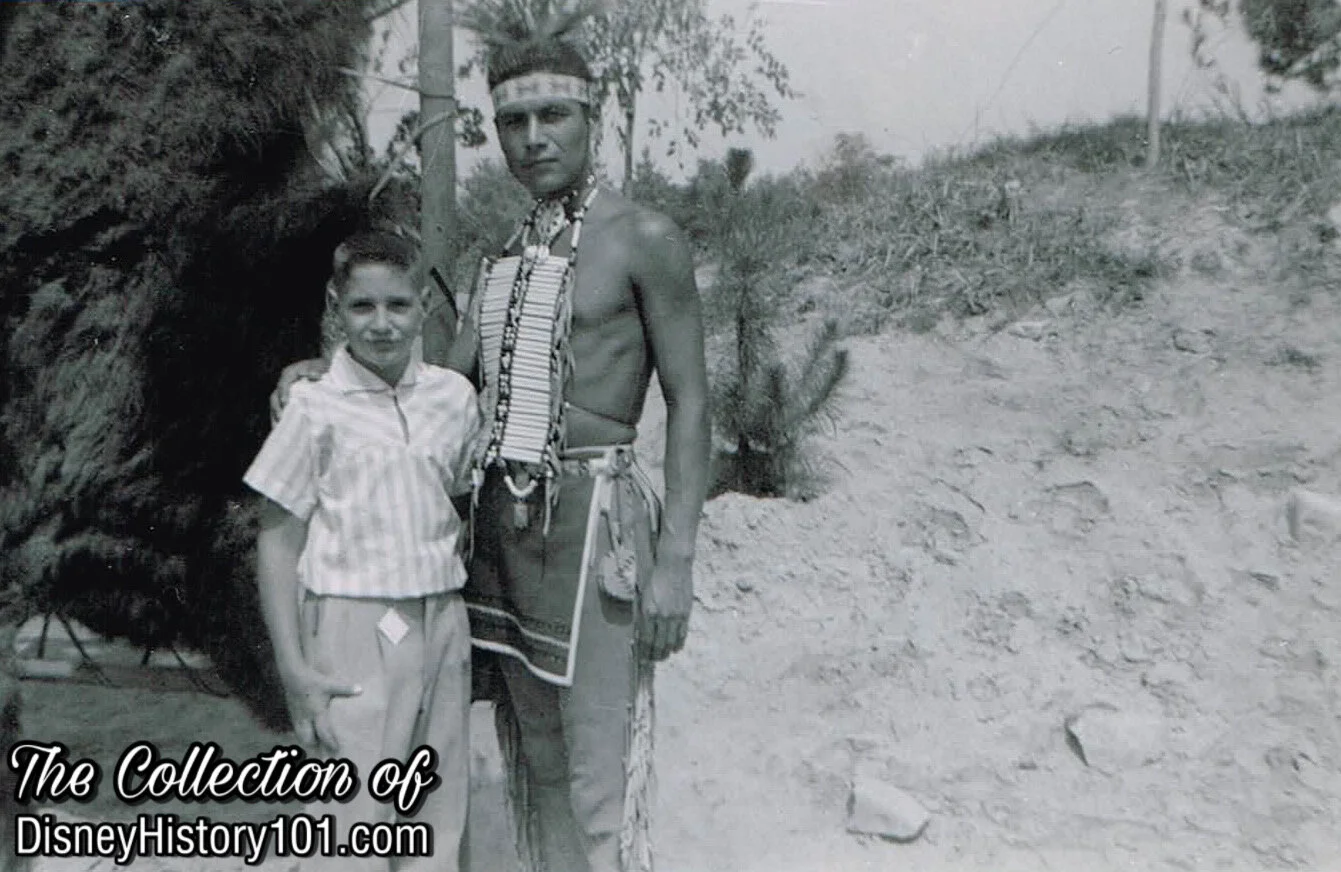

Vincent St Cyr meets a young guest in the original Indian Village, (c. 1955-1956)

Vincent St. Cyr (Left) and Unidentified Disneylander (Right)

“My father was one of the performers back then. He’s on the left. Vincent Saint Cyr [of the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska] . . . [performed] the Bow and Arrow, the Horse Tail, the Eagle Dance, and The Spear and Shield Dance, as I recall. Members of the group often switched out on the various dances, so most of the dances could be performed by most of the members (with the exception of The Hoop Dance, which was performed by only a few).

Vincent eventually became the emcee for the show. He sang traditional tribal songs for the dancers and educated the audience on the various tribal customs and traditions. I used to go with him to work where Disneyland became my babysitter for the day. Those were the days.”

From Left to Right : Eddie Little Sky (left) and Vincent St. Cyr (right) extend courtesy toward Korean Princess and V.I.P. Deokhye, c. 1961 - 1962.

“Maybe seven or eight years prior to this photo dad was in combat defending the Princess’ country. Dad was a sergeant in the Marine Corps deployed to Korea sometime in late 1952 or 1953.”

Now, Eddie Little Sky (left) and Vincent St. Cyr (right) demonstrate canoe paddling technique to Princess Deokhye (덕혜옹주 ; 德惠翁主) - the last Princess of the Korean Empire! As you will see, Indian Village performers often acted in the role of ambassador to guests from near and far.

Things weren’t all business for Vincent, who served as the coach to the DRC-sponsored Disneyland basketball team that competed in the open league of Anaheim, c.1962.

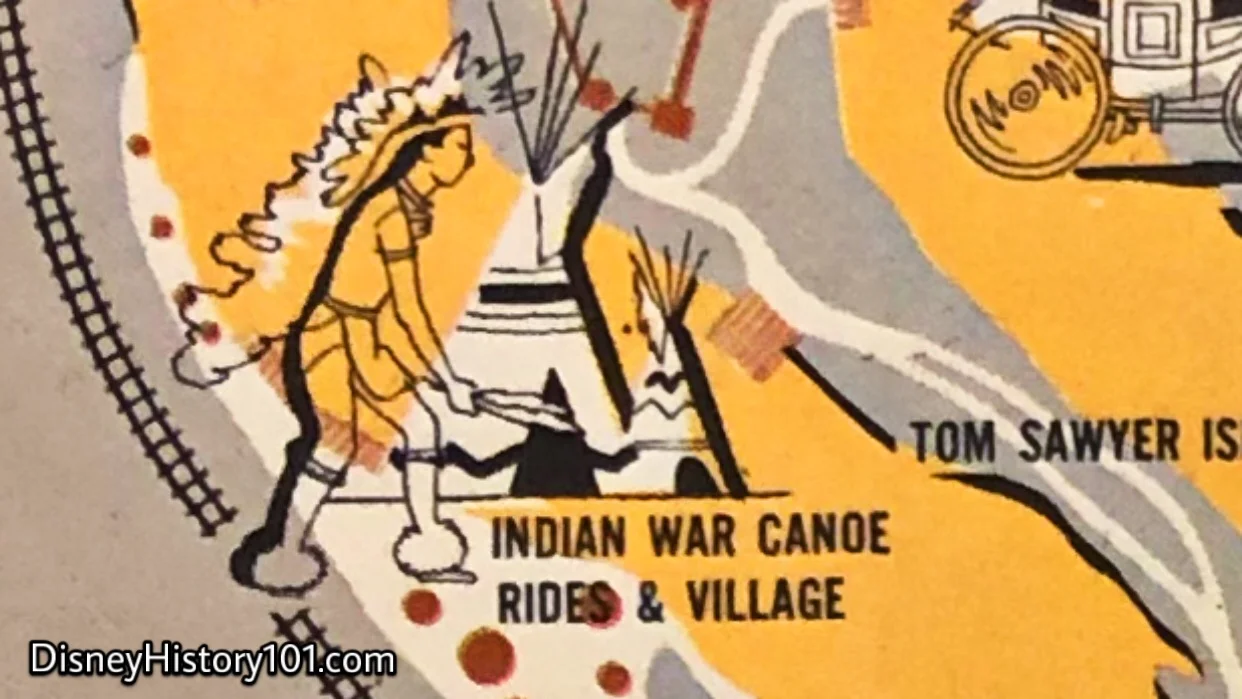

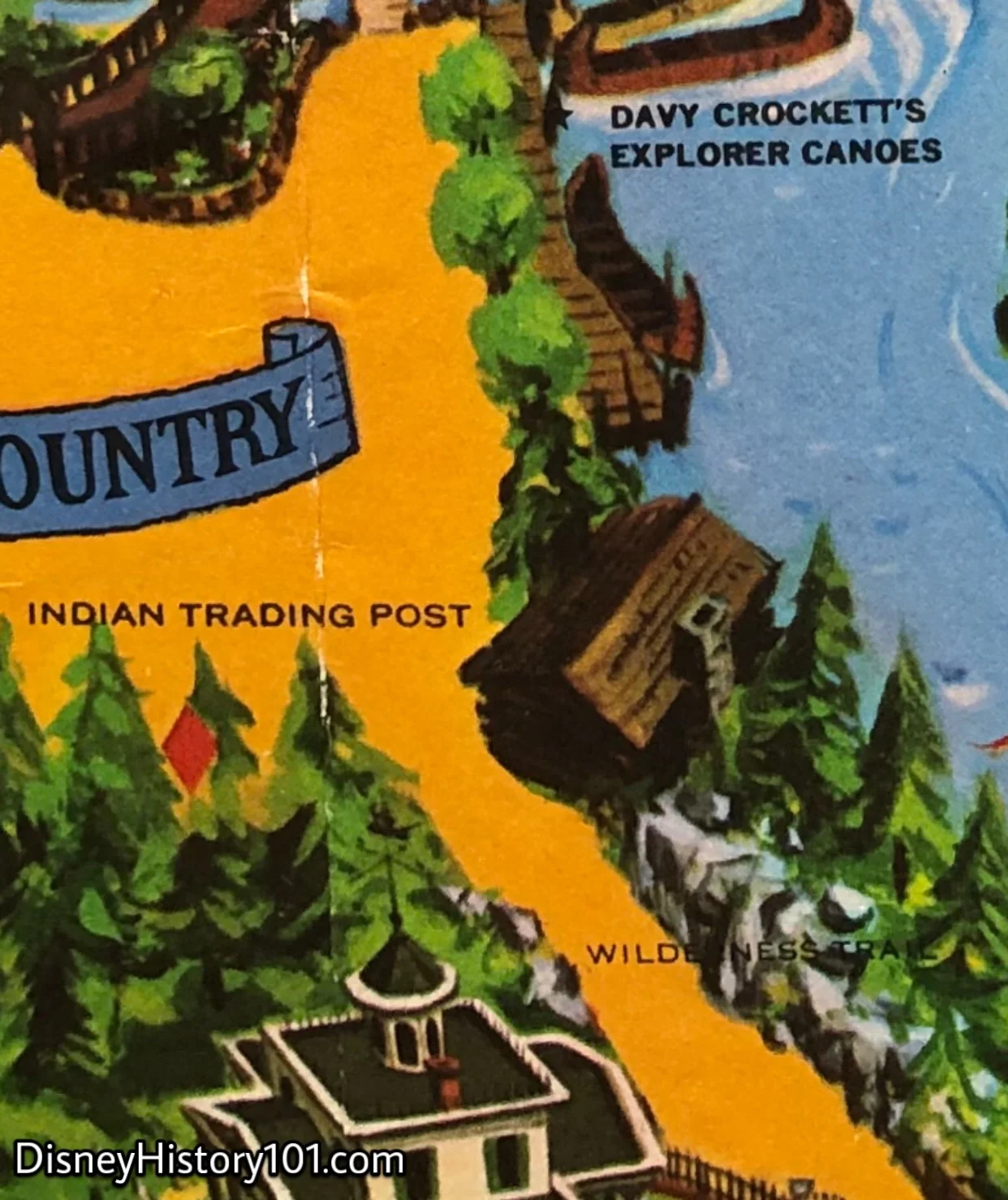

A c.1956 Complete Guide to Disneyland Excerpt.

With so many cultures to showcase, the talent quickly outgrew the small Adventureland location. Soon, another (more appropriate) area was considered, this time in Frontierland. This illustration (from a 1956 souvenir Guide, pictured above) teases the new larger Indian Village area of Frontierland with this simple illustration. But, things had really changed and expanded for the former Adventureland attraction. There was much more to see in the New Indian Village! Let’s take a look…

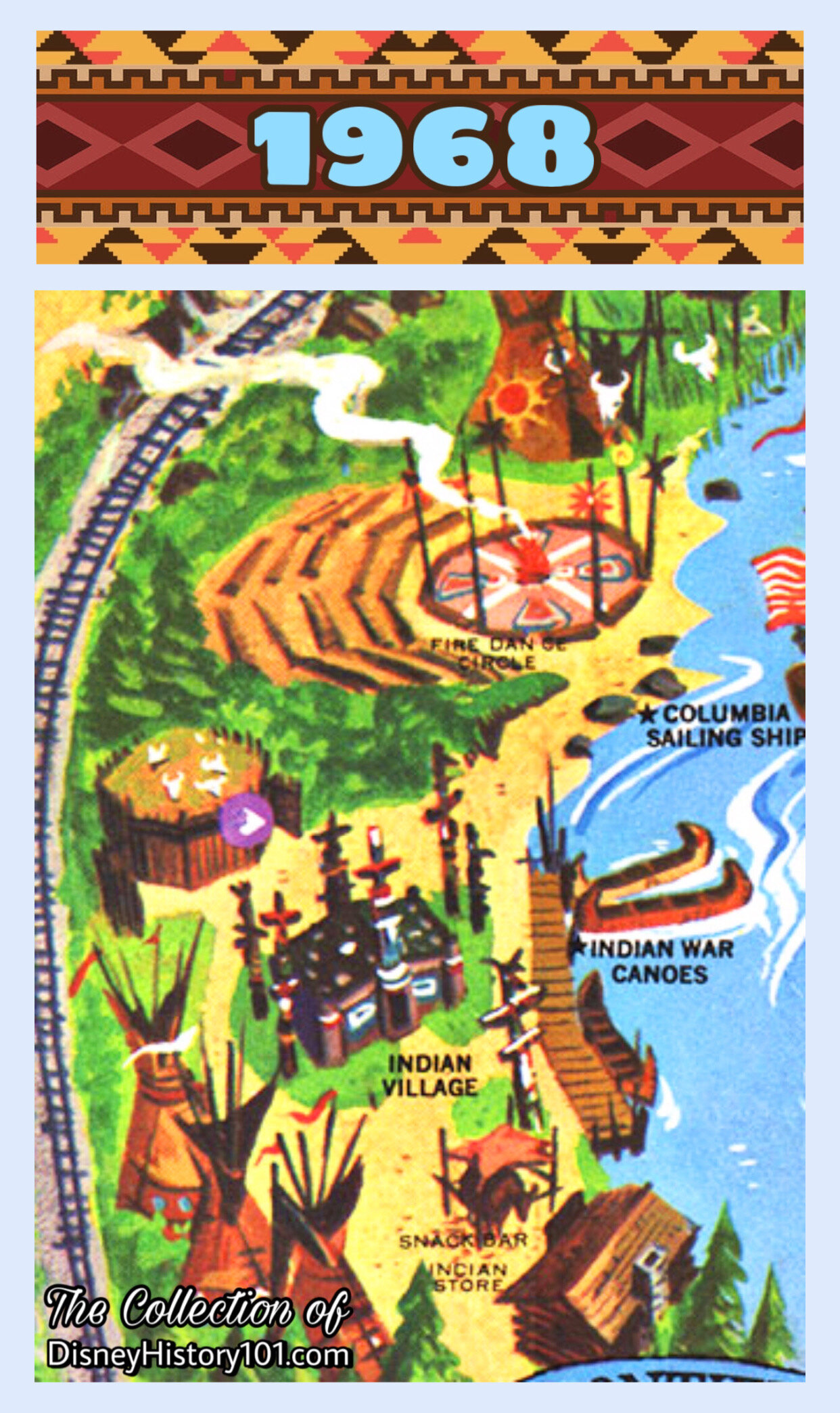

Frontierland location (July, 1956 - October, 1971)

Yes, the Indian Village (with its rich and diverse cultural display), had outgrown its small corner of Adventureland. Fast forward a few months, to 1956! It was now a half year after the first day of operation (during 1956), Disneyland received a $2-3.8 million expansion (through the course of the year). “Shortly after the first of the year, Walt Disney revealed his plans for the then distant summer season. In fulfillment of the promise made on opening day, that ‘Disneyland will never be completed’ Walt made public plans to add extensively to the Park’s facilities. Whole new areas were to be opened : a new Indian Village.” [‘Disneyland - 1st Anniversary Souvenir Pictorial”]

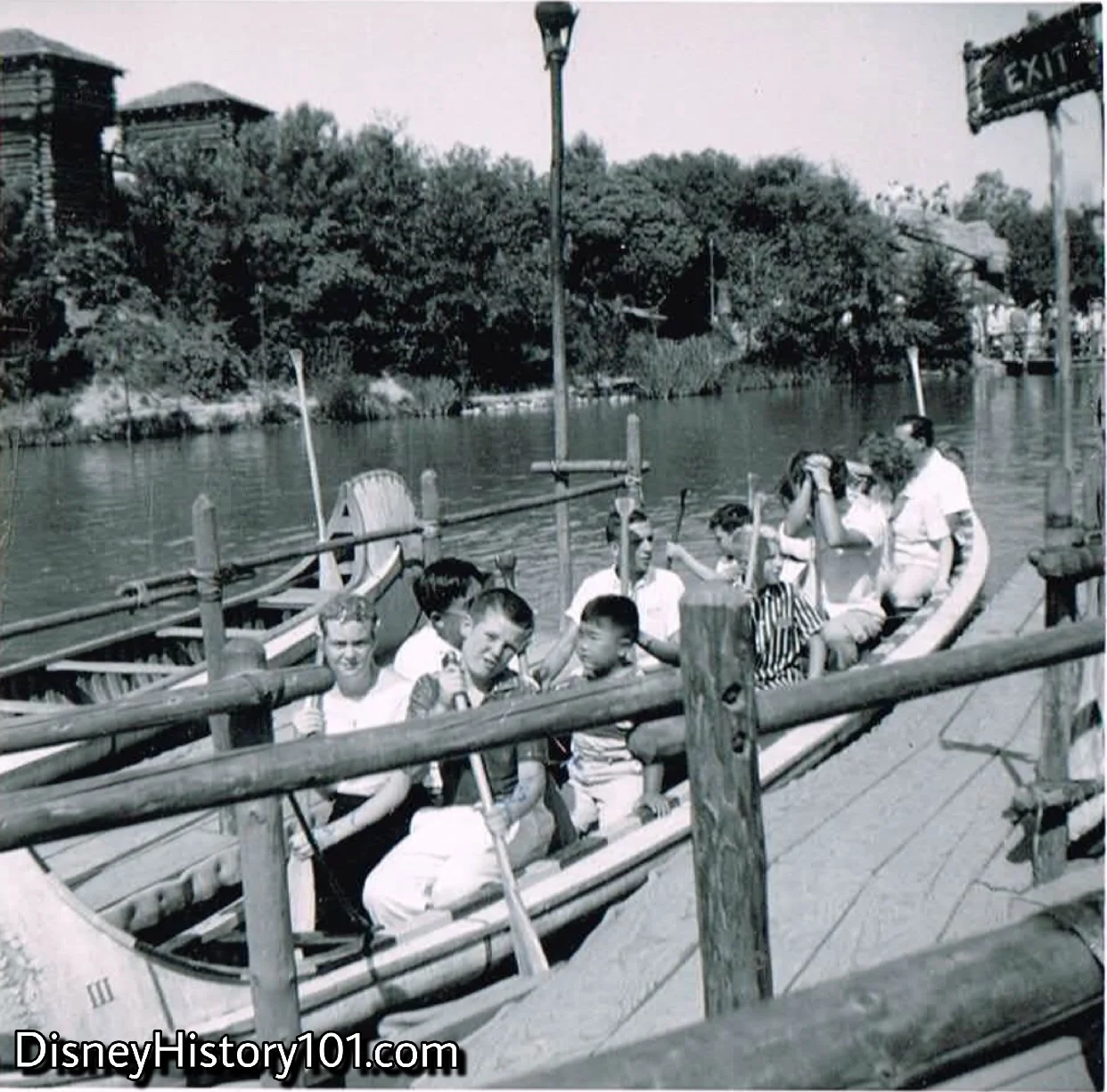

According to signage posted near the construction barrier, the new attraction would be called “Indian Museum Village.” About $100,000 gave the attraction a brand new (and appropriate) location along the c.1790-1876 shores of the Rivers of America, with ample room for archery displays and fitting for one of its star attractions - the Indian War Canoes (debuting July 4th, 1956)! Former original Indian Village performer Cheryl Clifford remembers this pivotal time when her family came to work for Disneyland :“It was 1956. I just turned ten, and my brother was going to turn nine years old. Eddie Little Sky had just been reading about Mr. Disney putting together an Indian exhibit. He and Vincent St. Cyr were involved in dancing and going to pow wows, and that’s how we knew them. We were hired right on the spot - no problem!”

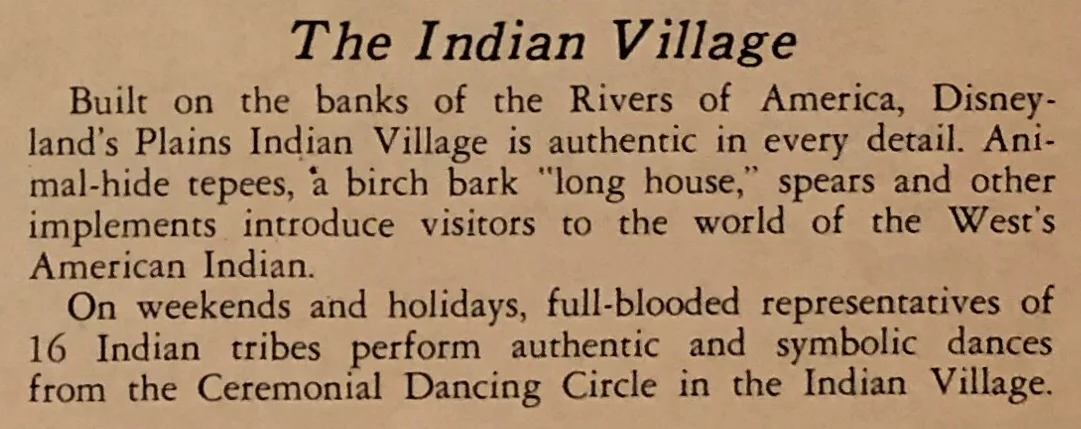

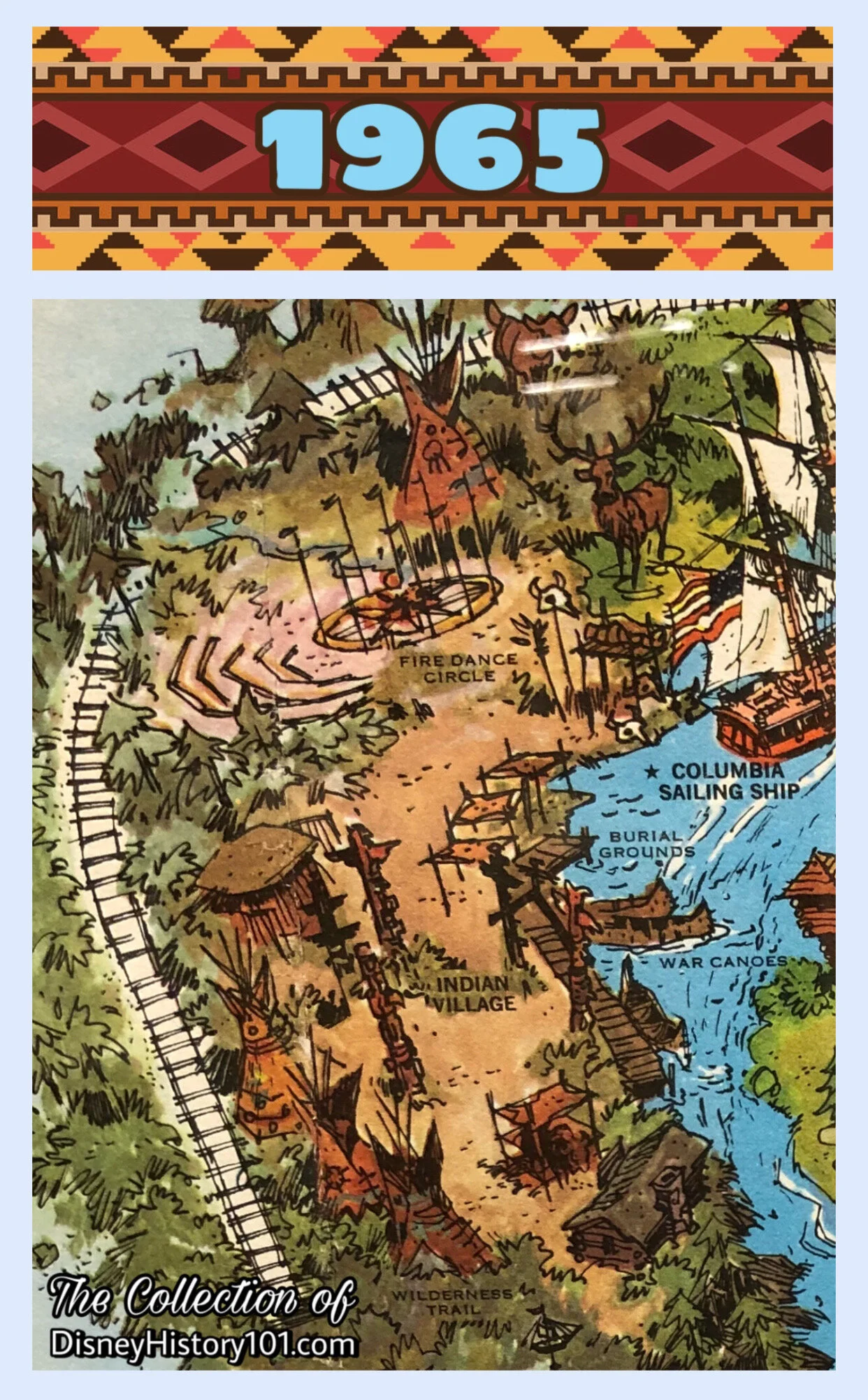

Guests (visiting from every state and 60 foreign nations), could now wander along the water’s edge, to the ends of the new “Wilderness Trail”, and through a “rocky pedestrian tunnel,” to discover The Indian Village (July, 1956 - October, 1971) - a free Frontierland attraction! Both Holiday magazine (published Summer, 1958) and Walt Disney’s Guide to Disneyland (published 1960), described this area as a “recreation of a Plains Indian Village,” though the cultural elements and character of many other Indian Nation’s regions were referenced throughout the land. Other documents added the character to include “over 100 years ago.” “The Disneyland News” (Vol.2, No.2 ; August, 1956) offered a somewhat archaic description of some of the exhibits - “one tent houses bead work, another shows the ceremonial pipes in the process of being crafted. Further on is the Medicine Man’s tent filled with the mystic and intriguing objects of this vital craft. Hard by the dancing circle is the Chief’s tent, tallest of the lot, arranged for the council to meet. Visible at the rear of the tent are the objects that signal the chief’s authority : the feathered flag of the tribe, his Coup stick, won in war by the chief and possessed by only the bravest Indians, the ceremonial pipe and the pallet, woven with the sacred designs that ward off the evil spirit as the Chief sleeps… Elevated several feet above ground level for better viewing , the audience sees a brightly decorated, circular surface, designed to be pleasing to the Great Spirit.” Still, a number of representatives would be on hand, to teach the old ways to visitors who would step into this portion of Frontierland.

The number of tribes represented would fluctuate over the years. For example, the narrator of “Disneyland U.S.A.” (released by Buena Vista Film Distribution, December 20, 1956) mentions “seventeen different tribes”. During the early years of the Indian Village, it was mentioned that “ceremonial dances” were performed by ten tribes (according to information schedules printed inside complimentary ticket books). The “members of 16 tribes” (representing the “Drum and Feather Club”) marched together in the “Disneyland ‘59” parade and pageant. Still as the months progressed, guests could observe select “Native American dances, crafts, and stories” from the True-Life descendants of “12 major North American Indian tribes” (by the summer of 1960, according to Vacationland), and again, “sixteen different tribes”. Cultural diversity was crucial, as Disneyland Holiday magazine impressed the importance of The Indian Village to Frontierland’s mission statement this way :

“One of the founding principles upon which Disneyland was designed was the preservation of our American heritage. This principle may be seen in many of the free shows and exhibits in each of Disneyland’s realms - and one of the most popular among many free performances is the preservation of Indian traditions and customs in Frontierland’s Indian Village…Among the tribes [and Nations] represented in Frontierland are Apache, Shawnee, Winnebago, Hopi, Navajo, Maricopa, Choctaw, Comanche, Pima, Crow and Pawnee.” In the words of “Honorary” Sioux Chief Truman (in Backstage Disneyland, Summer, 1965), “We’re here to represent our people and, naturally, we want you to know us and know about our race.” Occasionally these artists had the opportunity to represent their people on television. For example, brief footage of a parade of Indian Village Cast Members has also been amazingly preserved on film in the “An Adventure in the Magic Kingdom” episode of Walt Disney’s “Disneyland” television series (filmed in 1957, and airing in 1958)! This very footage (originally filmed in color) was reused for “Disneyland, U.S.A.” which was released theatrically in 1958. Other Indian Village Cast Members had the opportunity to share their culture on television, as when the Disneyland Indian Village became the stage for the production of the 10th episode of “Meet Me At Disneyland,” entitled “This Was The West,” airing on ABC in August of 1962.

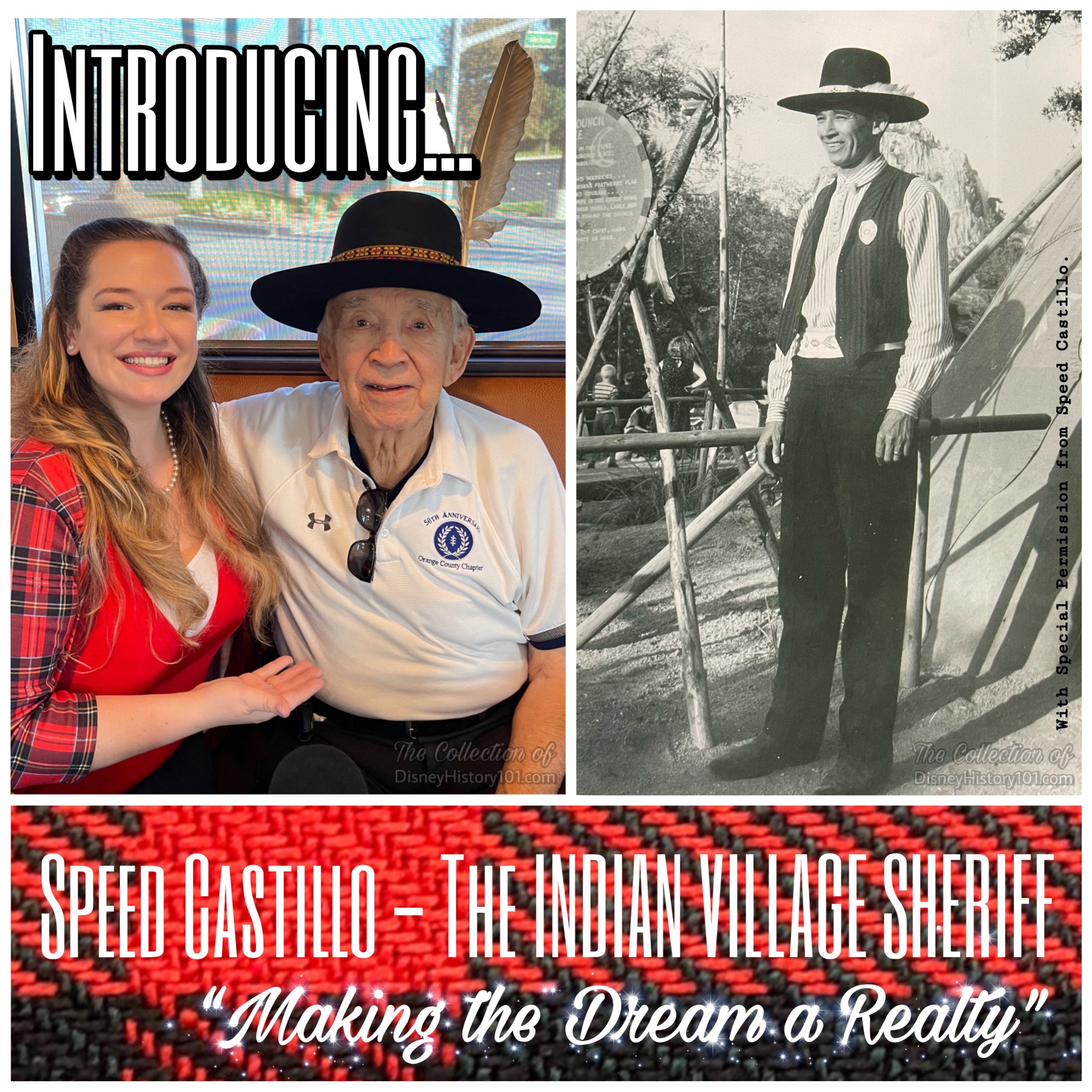

At times, Indian performers also acted as ambassadors, as when Jimmy Durante performed live radio from Indian Village. During the March 31, 1958, dedication ceremonies of the Grand Canyon Diorama, the 96-year-old Hopi Indian Chief Nevangnewa (alongside some Indian Village Cast Members and the young Little White Cloud) blessed the trains of the Disneyland Railroad that would take guests past the new diorama. Chief Riley Sunrise (adopted by the Kiowa ; of the Hopi Nation) and Chief Whitehorse (of the Otoe Nation) had the honor to welcome and escort Ethiopian businessman Ato Mehari Endale when he visited Disneyland’s Indian Village in 1962! Also of note, an unknown number of Indian Village representatives were also involved in welcoming Disneyland Guests to the “Thanksgiving With The Indians” (held during November of 1959), an event held “in conjunction with Zorro Days…”, where a Thanksgiving dinner was served in Frontierland. All of these exemplary individuals involved in representing their peoples were appropriately (and carefully) interviewed, selected, and hired through Bill “Chief Blackhawk” Wilkerson.

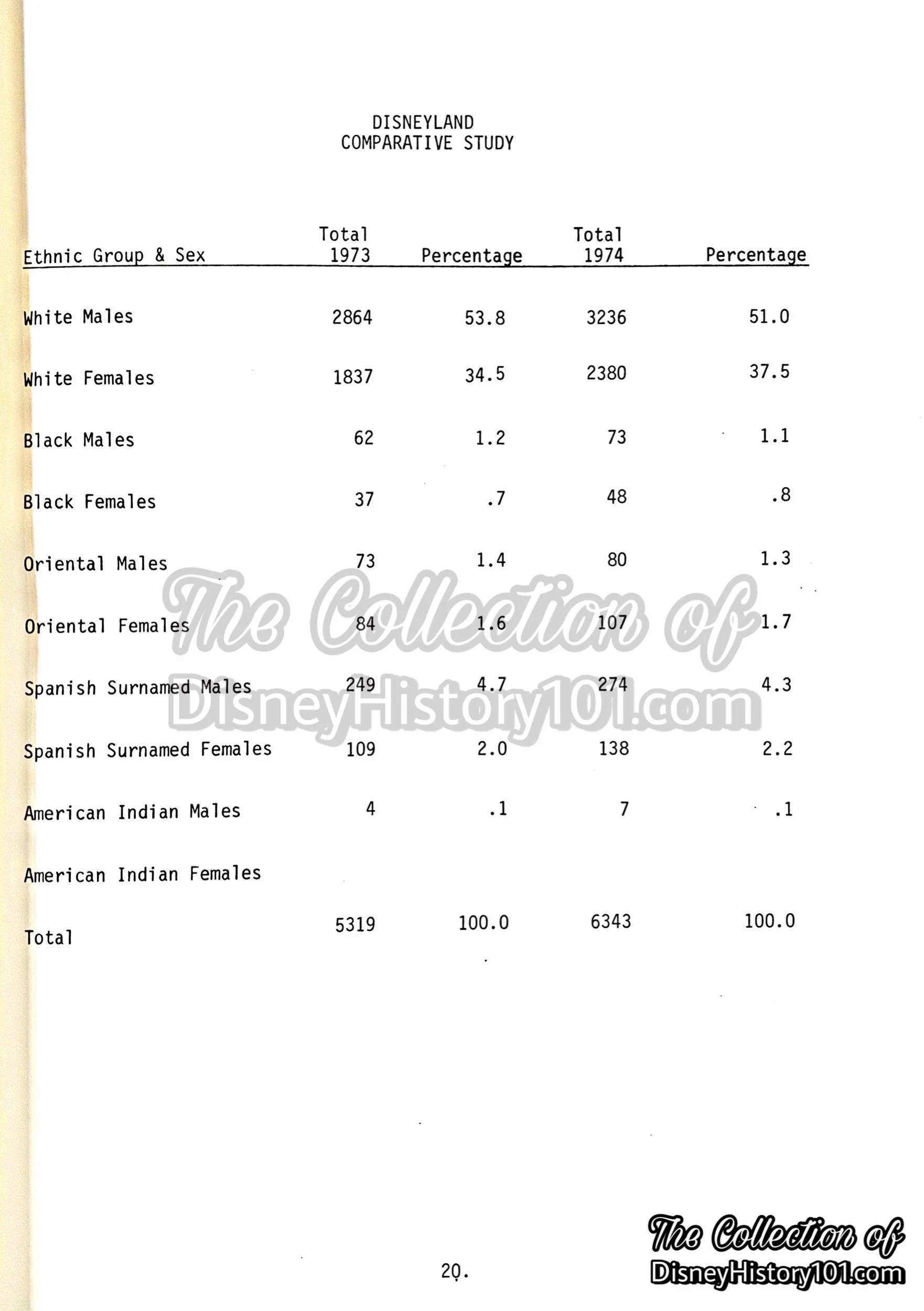

In addition to the privilege of sharing their cultures with large numbers of visitors, there were other perks. According to “Walt Disney and the Invention of the Amusement Park That Changed the World” by Richard Snow : “In 1957, the Soviet Press reported that Frontierland was holding Indians in captivity to amuse capitalist visitors, [but] Chief Riley Sunrise retorted ‘Captivity my eye! How many Russians make a hundred and twenty-five dollars a week?’” In actuality, the Disneyland Indian Village performers were treated very well, and paid an average of $35 a day during the late 1950s.

Among the exhibits was the Chippewa Longhouse (Front of House)

Years later, in response to a question about his “favorite part of Disneyland which is no longer there,” Bob Penfield in interview with Disneyland LINE (Vol.25, No.28 ; published July 16, 1993), “I used to like to go down to the Indian Village when they had the dance area or even before that when they had the birch bark lodge and the buffaloes.”

“Disneyland is unique in that some of the world's foremost creative artists and architects control all design at Disneyland.“ If the Chippewa Longhouse looks like an authentic representation, that’s because it was built under the oversight of Alexander Matthews Bobidosh - a Lac du Flambeau, Wisconsin native and then President of the Ojibwe (Chippawa) Tribal Council and a member of the First Nations. He was flown to Disneyland and assisted by several others on this project, like Laura Lobo, who crafted the cover. [More of Alexander’s story is preserved in Disneyland News, September 1956, page 8.]

The 12-foot high structure (made to “resemble World War II’s famous Quonset hut”) boasts “sewn” Birch & White ash bark roof, and frame work made of maple saplings laced with leather. Brief film footage of its construction can be seen in “Disneyland - The Park,” a short film created for the Disneyland anthology television series (first aired 1957). The narrator explains : “Nearby, descendants of America’s first ‘do-it-yourselfers’ build an Indian Longhouse. They apply birch barks strips in the same manner as their forefathers centuries ago. Cutting out the windows soon puts a finishing touch on the job.” This construction work was performed (without any barricades) in sight of guests.

The final structure would come to house the quick service “juicebar” as seen on Sam McKim’s faithful 1958 Disneyland map rendering. The Birch Bark House was leased by Bill Wilkerson for $100 a year. It was also operated by Bill Wilkerson and UPT Concessions. Their primary scope of sales was the self-titled “Fire Water” (soft drinks) but the building also housed the Indian store. The synergistic relationship between the commercial lessee William P. Wilkerson and Disneyland was good. William P. Wilkerson’s Bark Lodge yielded some revenue for Disneyland Inc. - $542 for the fiscal year ending September 29, 1957 and $2,902 for the fiscal year ending September 28, 1958.

The All-New Indian Village. The Indian Village Rafts began departure in 1957.

THE NEW INDIAN VILLAGE - Excerpt from Disneyland Holiday, Winter, 1957-58.

After the Indian Village was unveiled at its new location, the attraction of “an Indian Dance” was included among the events planned for the first anniversary of the Santa Fe & Disneyland Railroad (celebrated August of 1956), which was attended by 80 members of the Orange County radio and press publishers, staff members and their wives. About that time, this contemporaneous excerpt (pictured above) from one of Disneyland’s publications praises one of Frontierland’s not-to-be-missed attractions! During 1957, Walt Disney Studio employees who attended Walt Disney Studio day at Holidayland (on October 5, 1957) were treated to a special show featuring representatives of some of the sixteen tribes showcased at the Disneyland Indian Village. Vacationland (Summer, 1957) outstandingly mentions Chief Shooting Star (of the Sioux), Lee High Sky (of the Shawnee), Little Arrow (of the Winnebago), and Eddie Little Sky (of the Sioux) among those involved during this era. In addition, the Indian Village Rafts (particularly the Injun Joe) began operation ferrying Guests to Tom Sawyer Island during July 1, 1957. Considering all of these attractions, it is easy to see why by the year 1958, the Indian Village was considered one of 15 free educational shows and exhibits at Disneyland!

The All-New "Plains" Indian Village as spied across the water, (August, 1959)

One of the best pre-views of the new Indian Village could be achieved by scaling Castle Peak, Indian Hill, or one of Fort Wilderness’ towers on Tom Sawyer Island! But there’s only so much that can be experienced from the other bank of the Rivers of America. Those trees are blocking our view of their ceremonial dances. Let’s head down Wilderness Trail, and get a closer look.

The All-New Indian Village, (1950s)

From here, we can get a rough layout of the Indian Village's tepees, several Indian War Canoes, and even a River Raft belonging to that infamous Tom Sawyer Island character "Injun Joe". The Indian War Canoes had opened with the new section of Frontierland (on July 4, 1956, while Injun Joe’s Raft carried guests from the Indian Village Raft dock, which opened on July 1, 1957.

The All-New Indian Village, (1961)

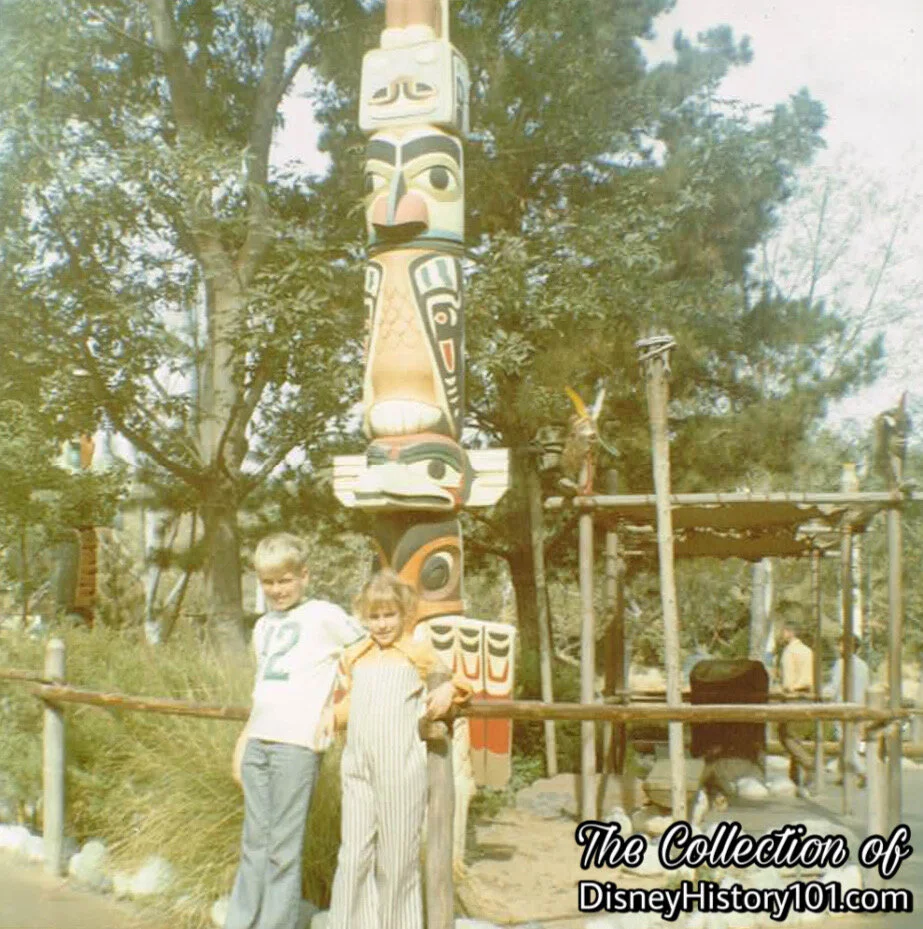

Wandering through the new exhibits of the Indian Village afforded guests the opportunity to explore what life may have been like in a true-life Indian village! As you make your way down the trail, be sure to stop and look at the markings on the tipis (used by the peoples of the Blackfoot, the Comanche, the Cheyenne, the Crow, the Kiowa, the Lakota, the Omaha, the Pawnee, and the Plains). The new teepee exhibits (with tipis installed and maintained by Al Alvarez and others of the Disneyland Drapery Department) told stories of life in a typical First Peoples Plains village. There was the Chief’s Council Teepee (an honored place with “objects symbolizing his authority” as the war bonnet, shield, lance, bow, and feathered flag), the Plains Indian Teepee (where guests viewed facsimiles of “ceremonial pipes” being made), the Medicine Man’s Ceremonial Teepee, the Bead Worker Teepee, and the Warrior’s Teepee (where an example of rawhide paintings were could be seen). As for the various representations of animals, people, and other figures on the “tepees” tell stories of “family and tribal events and great battles”.

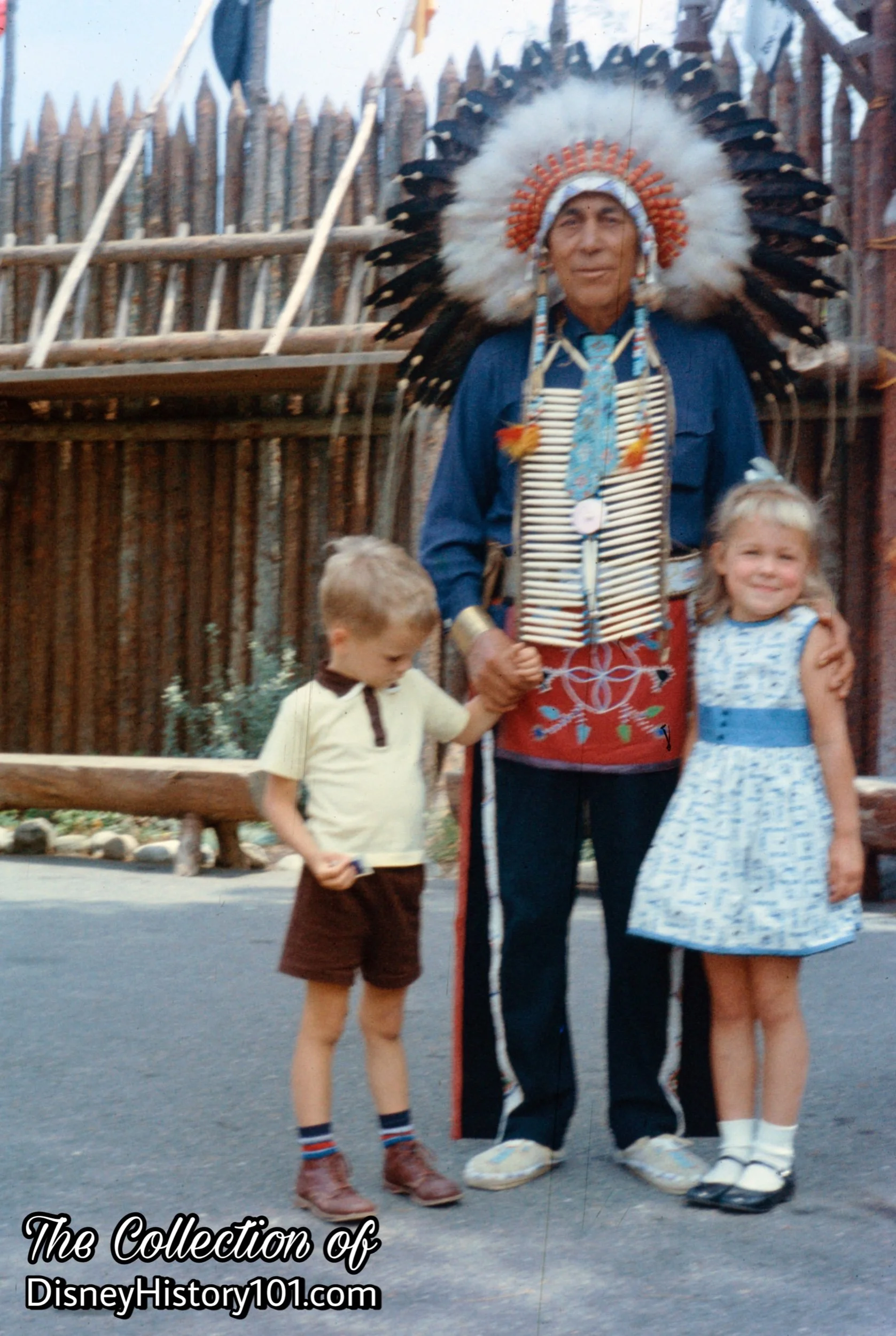

Chief White Horse (Truman W. Dailey) near the Western Plains "Teepees"

"Chief's Council Tepee" Exhibit and Guests.

"Chief's Council Tepee"

Buffalo (American Bison) and "Chief's Council Tepee" Exhibit

The Sacred Buffalo (American Bison) Exhibit.

The Sacred Buffalo (American Bison) Exhibit, (November 14, 1957)

The original “Indian Village” displayed a pelt of an American Bison. Now, a stuffed Bison was kept on display in the Indian Village, for guests who hadn’t seen an American Bison in person. This display helped guests understand some of the animals that Indians had interaction with while living in “frontier” America. The Native American had respect for the animals of the land, only hunting them when it was necessary for food, clothing, or shelter.

It is important to mention that (not withstanding the animals featured in the Grand Canyon Diorama) this was one of the few true-life mounts ever utilized in the Park. Still (like many of the pre-1962 land animal figures of Disneyland) the Buffalo featured natural skin. In order to maintain these, Disneyland hired a taxidermist. After the original taxidermist quit (due to the implementing of synthetic “skin”) Bob Johnson (c. 1960 Park taxidermist of the Disneyland Staff Shop under Bud Washo) maintained “Show Quality” of this exhibit (before the term was officially coined). According to Backstage Disneyland (Fall of 1965) : “The children visiting the Indian Village began using the back of the stationary buffalo for a slide and as they slid over his rump they would pull of his tail. Bob inserted a steel brace and welded a cable to it. Now the kids still slide but the tail doesn’t come off.”

The sacred Buffalo (America Bison) Exhibit.

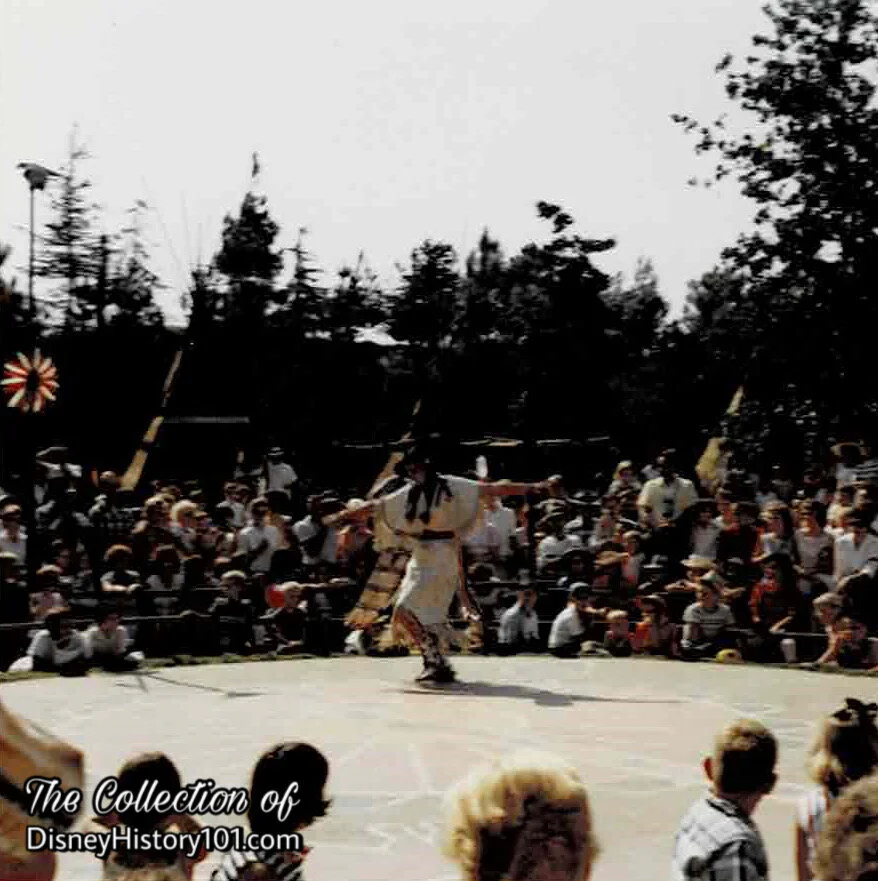

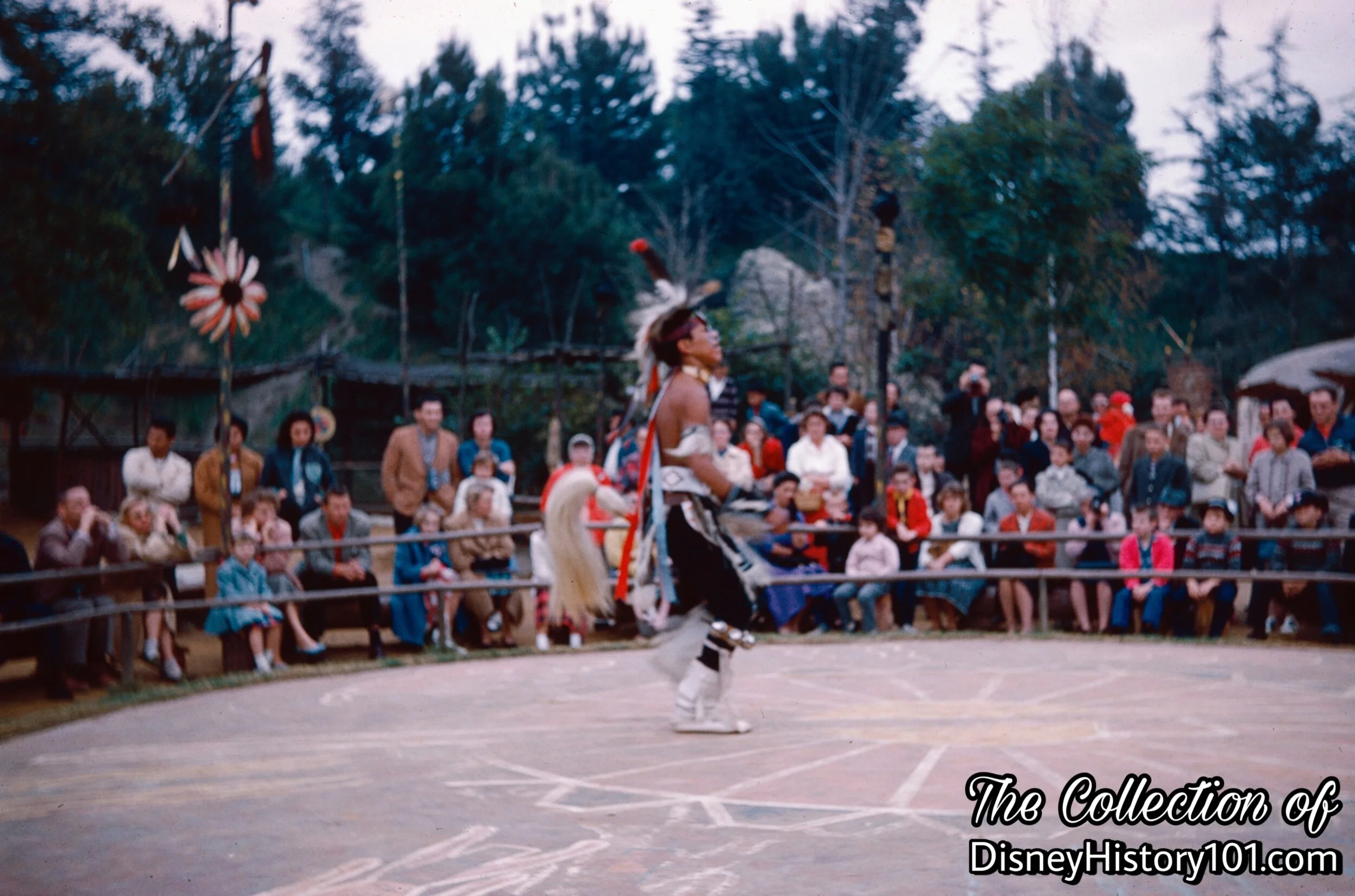

Ceremonial Dance Circle, (October, 1960)

Disneyland hosted a number of “free shows” during its first few decades, but the Disneyland Indian Village’s Ceremonial Dance Circle was by far one of the most popular free Disneyland attractions! Here, we can see guests awaiting the start of the next free show at Ceremonial Dance Circle. Ceremonial Dance Circle was so popular that it was eve featured on a number of standard and panoramic dimension post cards that were sold in Disneyland from the late 1950s to the early 1960s.

Host Louis Heminger - "Chief Shooting Star" and a young VIP.

Walt once said “Disneyland would be a world of Americans, past and present.” [Words From Walt, 1975] There were few locations in Disneyland which captured this spirit more than at the Disneyland Indian Village.

Louis Heminger invited people to come and enjoy his way of creating happiness. He loved interacting with Guests of all ages. During one segment of “Disneyland U.S.A.” (released by Buena Vista Film Distribution, December 29, 1956) he even can be seen holding a baby during the show at Ceremonial Dance Circle. In August of 1962, Lloyd Richardson, Larry Clemmons, Joe Marquette, Coy Watkins, and Jack Leppert (of the Walt Disney Studio) filmed and shot scenery for Studio Production #3185. During this visit, “ride operators and characters were used in their street clothes” as portraying guests, of whom Ron Hemminger was included.

Louis Heminger Ceremonial Dance Circle

Louis Heminger (Chief Shooting Star) continued to preside over some ceremonies at Ceremonial Dance Circle in the all new Indian Village. Only now he was joined by several others, taking turns, or “co-emceeing”. Both Louis Heminger and Riley Sunrise can be seen sharing this responsibility from this very location in “Disneyland U.S.A.” (released by Buena Vista Film Distribution, December 20, 1956). The narrator (of the very same film) divulges that this “organized group uses this traditional setting in their festive activities. All such groups are welcome to come here and perpetuate their ceremonial customs and centuries-old cultures”.

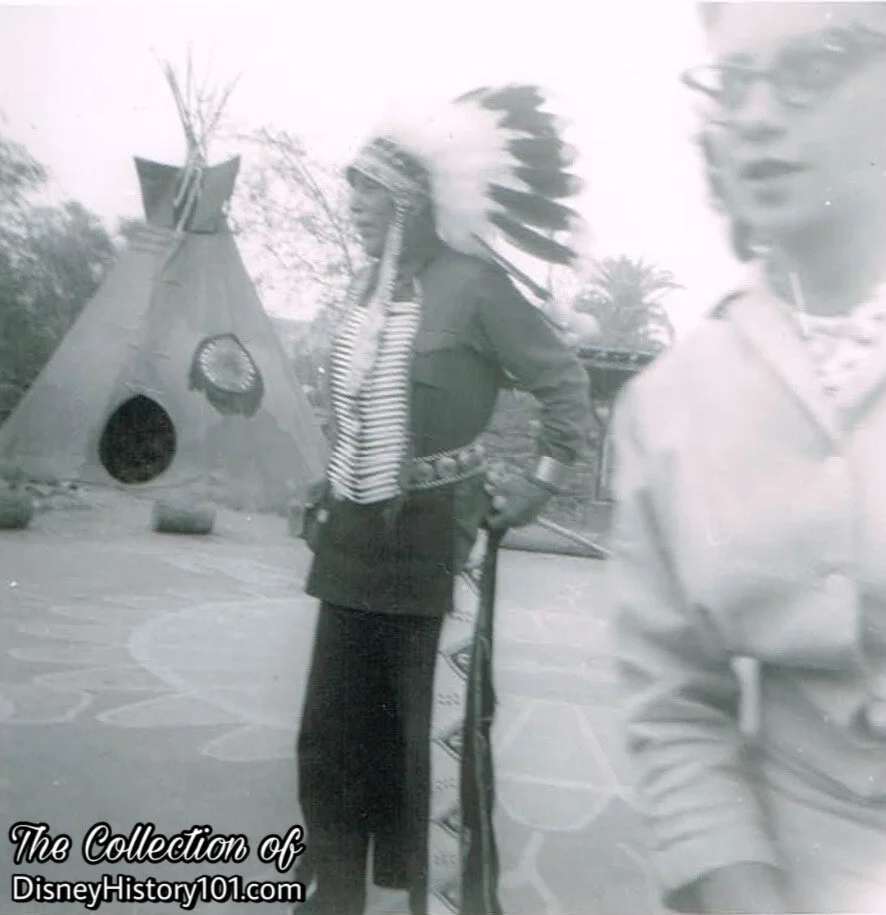

Chief Whitehorse at Ceremonial Dance Circle, (October, 1961)

Retired “Chief Whitehorse” (Leader of the Otoe Tribe, Red Rock, Oklahoma) welcomes guests as he supervises, narrates, and leads the demonstrations by Disneylanders at Fire Dance Circle in the Disneyland Indian Village. According to an official Indian Village Show script (revised February 12, 1966) a typical show would have began in a way like this:

“Good morning, friends…. and welcome to our Indian Village. We hope you will enjoy your visit here, today. I will be your narrator for this program. My name is ‘Chief Whitehorse.’ I’m a member of the Otoe Tribe from Red Rock, Oklahoma.”

This introduction was followed by a “singer-drummer” who enters and takes his position at the drum.

Chief Riley “Quoyavema” (Kwayeshva) Sunrise narrates a show.

The show narrator would continue:

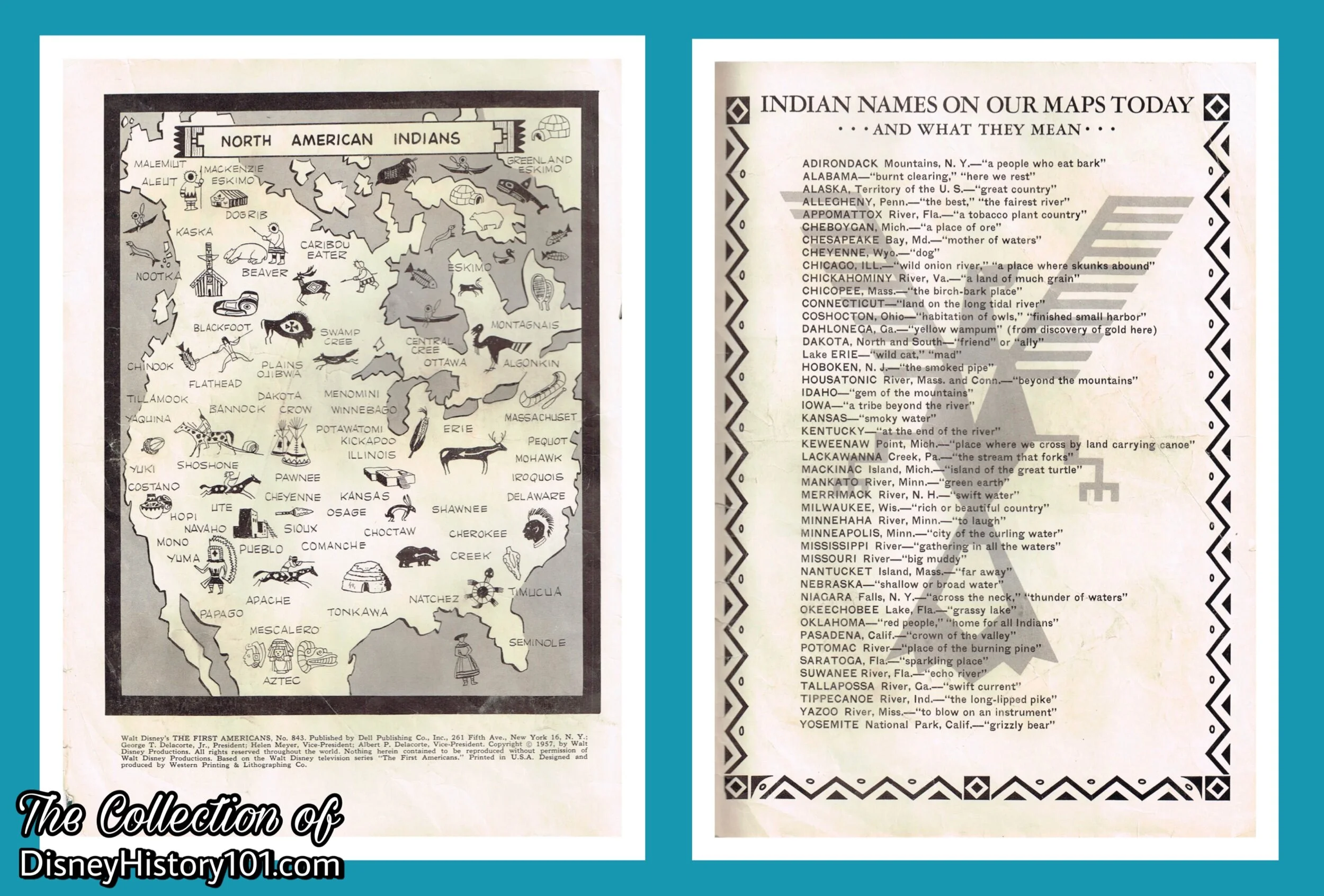

“History tells us that man first appeared in America over 25,000 years ago. Though the years they divided into distinct groups and within those groups were many tribes with different names, different customs and different languages.

When Columbus landed on the East Coast thousands of years later, he did not know that the people he met were the descendants of these first discoverers of the New World. He thought he had landed in India and he called our ancestors ‘Indians.’

Today, there are 279 Indian Tribes in what is now known as the United States. This count doesn’t include the new states of Alaska or Hawaii, although there are some of our people in Alaska, as there are in Canada, Mexico and in Central and South America.

The Indian of this country can most easily be divided into five major groups. These divisions are made by various geographical regions or areas. Our Village here in Disneyland is set-up to represent, as nearly as possible, these five major groups.

The Indians that I think you’ve heard the most about are the plains Indians. They made their livelihood primarily by living a semi-nomadic existence, following the American Bison, or Buffalo. There are 65 tribes in this group. They occupy the great Central Plains area and are represented by this dwelling behind me. It is called a tepee. The tepee is very easily assembled, taken down and carried across the plains.”

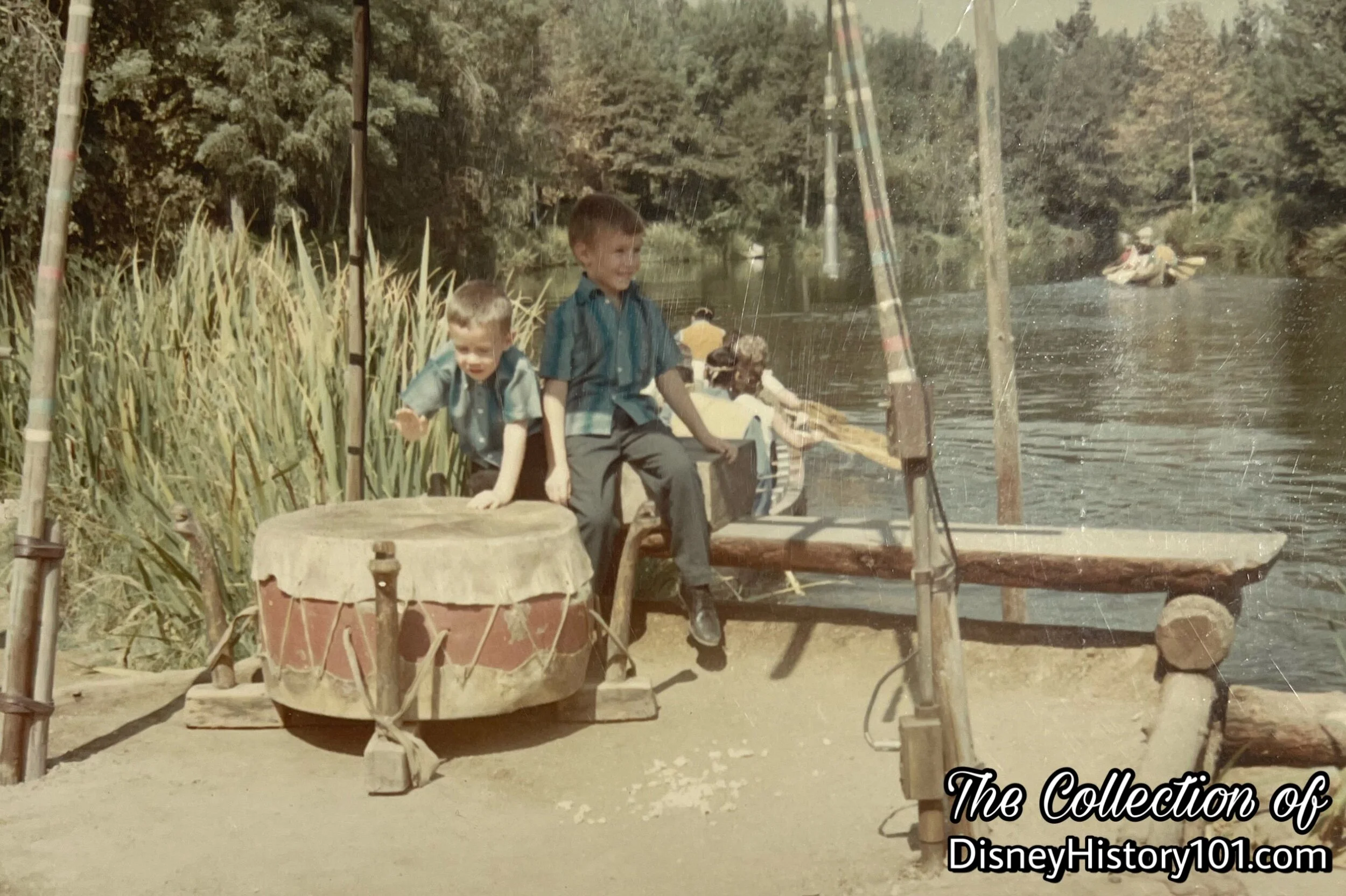

The Ceremonial Dance Circle Drum and four "Singer-Drummers".

The Narrator continues: “Normally at our Pow-Wows, we place our singer and drummer in the center of the dance area, but, here, due to limited space, we have placed him to the side and he often tends to go unnoticed. He is one of the most important performers in our program and, without him, our presentation would not be possible.” The drummer for the show was then introduced by name, tribe, and home, before being given commendation: “He is doing a fine job for us today and I’d appreciate your welcoming him.”

Musical instruments like the drum were essential to the conveying of stories, and Fire Dance Circle appropriately held one large Navajo traditional-style drum (which the white man referred to as the “Tom Tom”). Many tribes made use of the drum including some Pacific Northwest nations, Mexican nations, and Alaskan nations. The beats against the stretched skin of this particular Navajo drum, resonate across the Rivers of America, and can be heard as far away as Main Street U.S.A.!

The Ceremonial Dance Circle Drum and three "Singer-Drummers."

According to “THE DISNEY THEME SHOW - an introduction to the art of Disney outdoor entertainment”: “Important are the sounds which permeate the scene, for without them, the theme show is a silent movie . . . but with them it is a symphony of music, effects, and natural sounds that the finest stereo system in the world can't duplicate. These sights and sounds are provided not only by imagineered attractions and shows, but also through the multi-talented efforts of live entertainers . . . in special musical groups . . . in parades and pageants . . . providing an everchanging backdrop to virtually every area in the theme show.”

Here, multiple musicians would perform demonstrations at the drum (at the same time), and provide the tone for each dance performed. A brief scene of “Disneyland U.S.A.” (released by Buena Vista Film Distribution, December 20, 1956) preserves a rare occasion of six tribal representatives sitting around the Ceremonial Dance Circle Drum!

Ceremonial Dance Circle Narrators and friends, (June, 1960)

Representatives from other tribes (as well as their family and friends), would stand back, watch, and learn as turns were taken in the circle.

The c.1966 narration continues:

“The Plains Indians most popular social dance was known as the Omaha Dance, from the tribe that originated it. This Omaha Dance was intended to imitate the hunt. In became known, in some areas, as the Grass Dance, and each tribe had its own name for it. But, since the coming of the paleface, it has taken on a hostile name. It is known today, quite commonly, as the War Dance!”

According to the aforementioned official script (revised February 12, 1966): “Dancers run from the tepee onto the dance circle as they, and the singer, emit loud war-whoops. The War Dance is played ‘medium-fast,’ 1 1/2 times through the song, and goes right in one more complete chorus, played and sung at top speed. At the completion of this, and all dances, the dancers finish with their feet facing the audience. They raise their right arms to acknowledge the applause, turn and run back into a tepee.”

Representatives look on at Ceremonial Dance Circle

Most Disneyland Indian Village guests watch the demonstrations from behind the log railing.

Ceremonial Dance Circle, (August, 1958)

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE, (1961)

Unidentified Female Representative (left) and Dawn Little Sky (right), (August, 1959)

Dawn Little Sky (Eddie Little Sky's wife, pictured right) and a currently unidentified female performer (pictured left) present a cultural experience to the guests at Ceremonial Dance Circle! It was common to see women (like Dawn Little Sky, Ruthe “Pretty Star” Homer, and others) narrating portions of the main show. Dawn was one of the more outstanding female performers in the Frontierland Indian Village. She was often seen in contemporaneous photographic advertisements and publication images featuring the Indian Village (i.e. Vacationland, Summer 1963). In 1964, Ruthe “Pretty Star” Homer - a previous Miss Indian America (but, of the Gros Venture tribe of Billings, Montana) - spent the summer of 1964 with the Disneyland Indian Village Productions Department. According to “Backstage Disneyland” (summer, 1965), she “represents her people well and acts as hostess, announcer, and dancer throughout the summer season.” Vivian Arviso another Miss Indian America (of 1960) of the Navajo spent some time at Disneyland answering Guest’s questions about her people! She felt strongly that “the tourists really needed to be able to ask questions and not just watch Indians dance or do sand painting or do a textile weaving”.

If anyone recognizes this unidentified woman (on the right side, in the photo above), please contact Disney History 101’s online museum docents and curators. We would sure love to hear from you!

Dawn Little Sky, (August, 1959)

Though the dancing was mostly traditionally demonstrated and performed by the men of these representatives of First Peoples, women (like Dawn Little Sky) played a large role in sharing their cultural heritage with the guests! Here, women demonstrated some dances, created examples of arts and crafts, and even hosted segments of the shows in Ceremonial Dance Circle. We will meet just some of the women in this gallery, and learn of some of their contributions, as well as their memorable impact on guests, fellow Disneylanders, and their present family members.

Dawn Little Sky Emcee of an Indian Village Show

Unidentified Female Indian Village Representative and Emcee

c.1960

Unidentified Female Representative.

The Buffalo at Ceremonial Dance Circle

Many of the “Plains Indians” (that lived a nomadic life in tipis, at times), depended on the herds of buffalo that lived in the region. These peoples included the Arapaho, the Assiniboine, the Blackfoot, the Cheyenne, the Comanche, the Crow, the Gros Ventre, the Kiowa, the Plains Apache, the Plains Cree, the Plains Ojibwe, the Sarsi, the Shoshone, the Sioux, and the Tonkawa (to name but a few). Many of these peoples practiced some sort of respect to the sacred animal. In a demonstration of one such “Buffalo Dance” (with special permission), Vincent Saint Cyr (of the Winnebago Tribe) portrays the hunter stalking his game, in an act that will mean nourishment, and life.

The Buffalo at Ceremonial Dance Circle

This dance seems to have been performed with representations of at least two sacred Plains Indian relics - the Eagle Staff, and the Buffalo Warbonnet. Using the Eagle Staff, the Plains Indian has defeated the mighty Buffalo (portrayed by the performer wearing the Buffalo Warbonnet). The return of the buffalo herds were celebrated with this dance, which meant food, and life for the peoples.

The Buffalo at Ceremonial Dance Circle, (October, 1960)

Another dance is demonstrated with the use of the Buffalo Warbonnet.

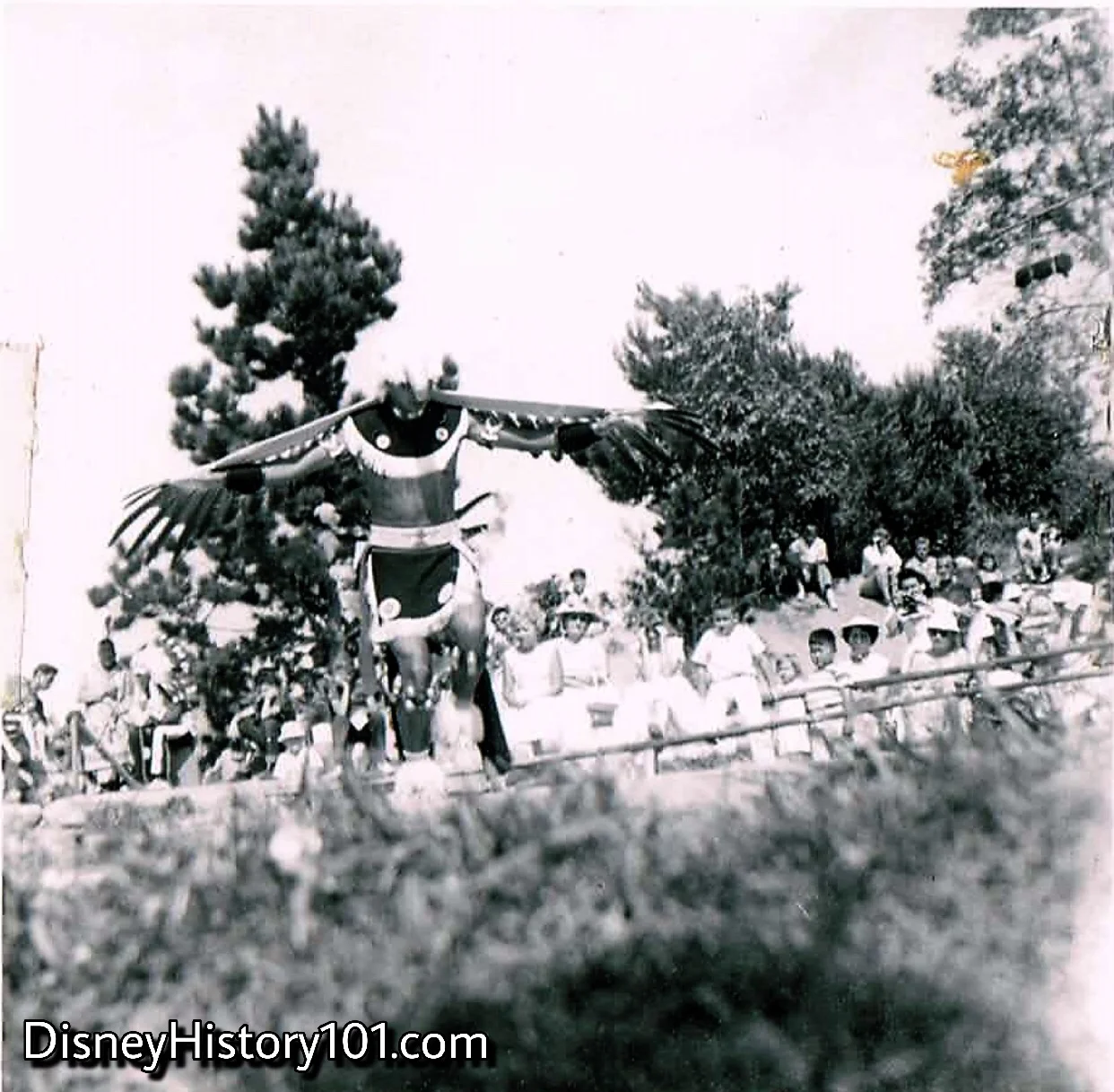

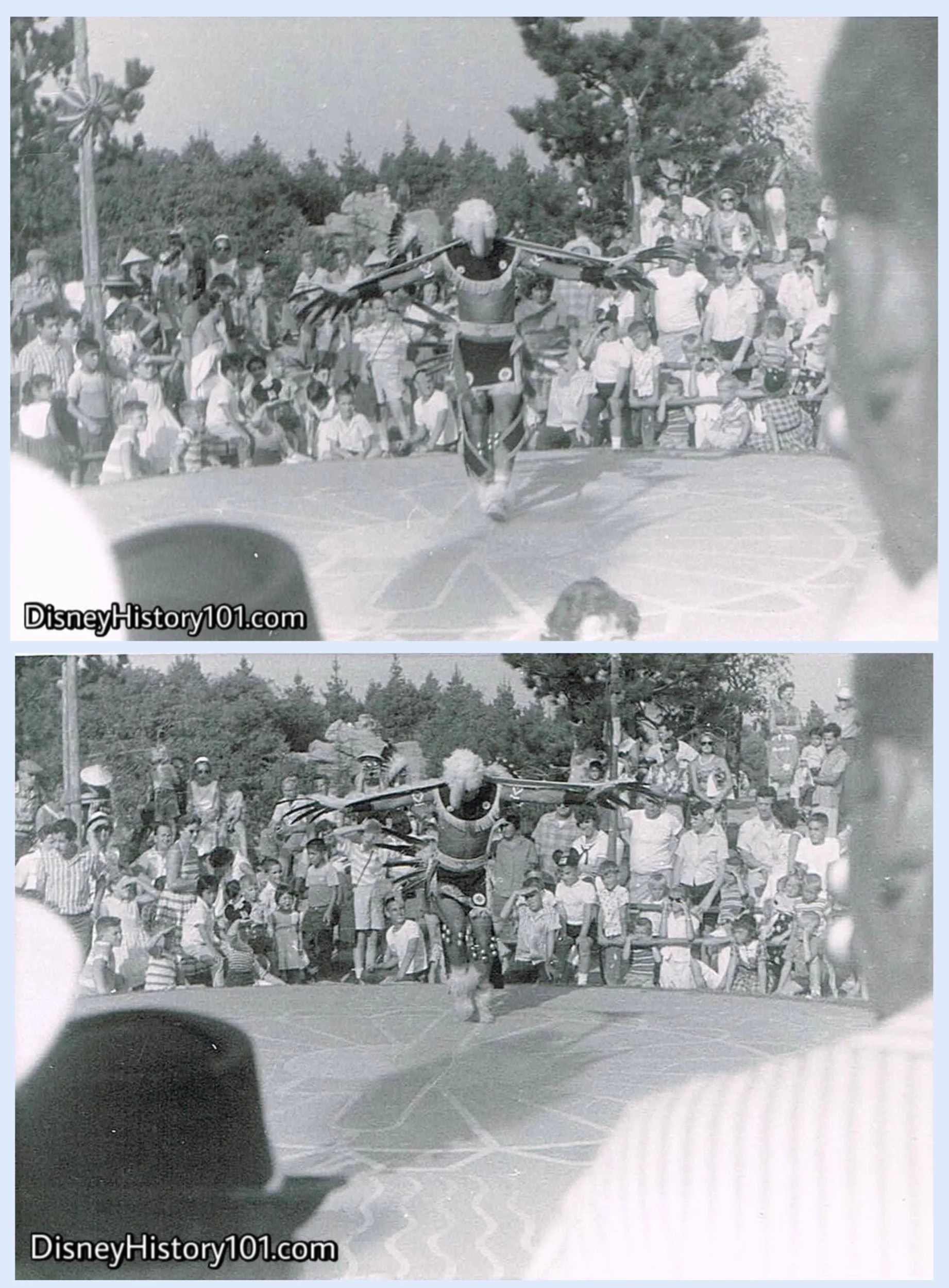

The Eagle at Ceremonial Dance Circle, (August, 1958)

Some tribes perform what is called the Eagle Dance (including the some of the 19 Pueblo peoples, and the Iroquois, to name a few). Here, we have seen the dance demonstrated by one to (as many as) three individuals at one time. Disneyland LINE Indian Village representatives continue : “The Eagle Dance was brought about by the Indians wanting to show some respect for the great bird they admired so much. It is done by simulating the actions of an eagle both in flight and on the ground foraging for food.” The steps are performed (in time with the drum), and the bells (on the ankles of the performer) ring.

The Eagle at Ceremonial Dance Circle

Two Indians generally represented the soaring eagles in the “Eagle” dance!

The Eagle at Ceremonial Dance Circle

The Eagle at Ceremonial Dance Circle

The Eagle at Ceremonial Dance Circle, (1961)

The Eagle dance.

The Eagle at Ceremonial Dance Circle

The Eagle dance.

The Eagle at Ceremonial Dance Circle

The Eagle at Ceremonial Dance Circle

The Eagle dance.

The Eagle at Ceremonial Dance Circle

The Eagle at Ceremonial Dance Circle, (c. 1956-1957)

The Eagle Dance.

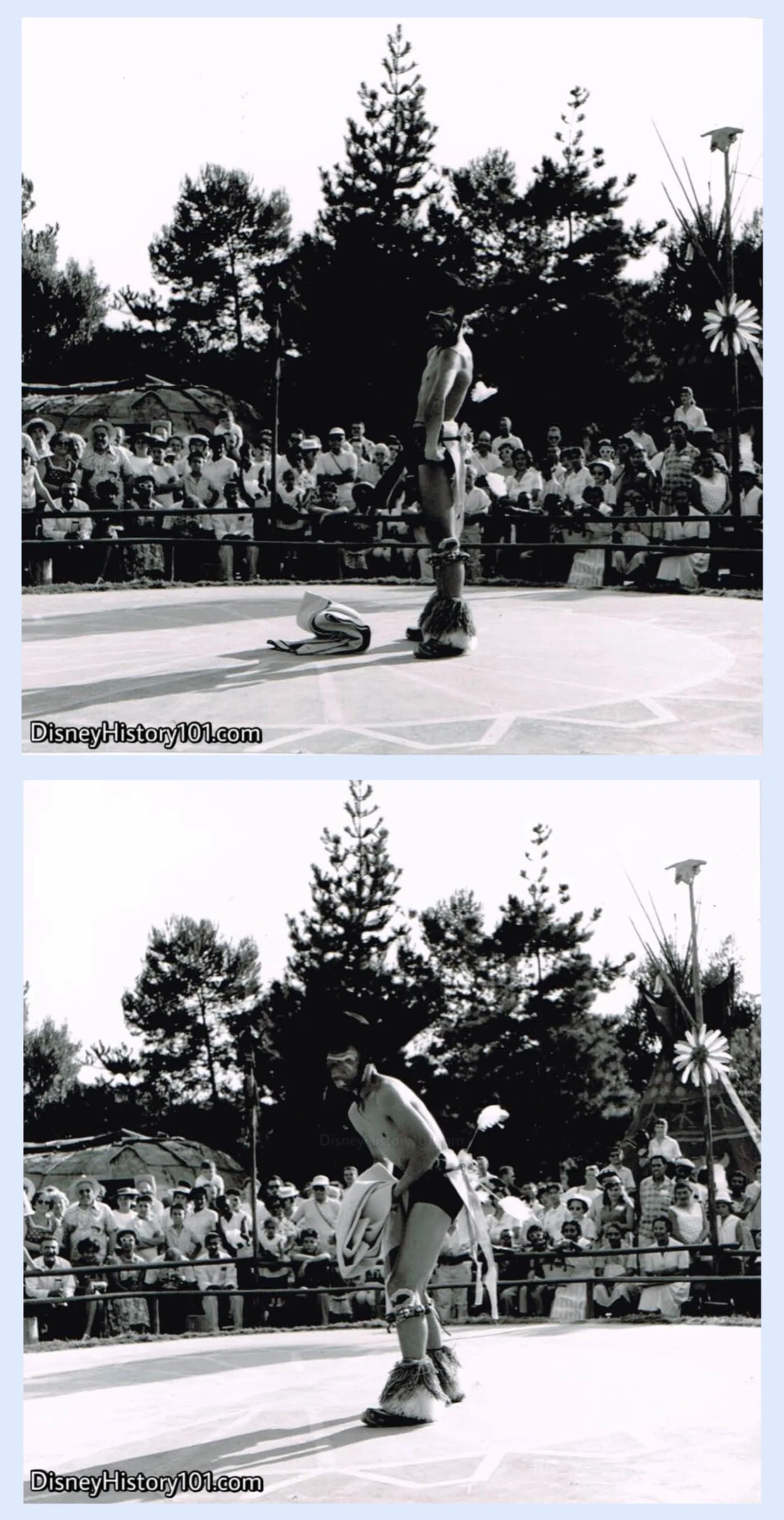

The Horsetail Dance at Ceremonial Dance Circle.

The Horsetail Dance at Ceremonial Dance Circle.

The Horsetail Dance at Ceremonial Dance Circle.

The Horsetail Dance at Ceremonial Dance Circle.

The Horse Dance (or, “Horsetail Dance”) is performed and preserved by the Sioux and Pueblo peoples, among other nations. Indian Village representatives explain to Disneyland LINE magazine : “To show or demonstrate one of the most recent dances developed by our forefathers we select the Horsetail Dance. As you know, the horse is not a native of this continent. The Spaniards introduced the horse to us around 1600 A.D. This most magnificent animal soon grew invaluable to the Indians. To show our appreciation as well as to honor the horse we perform this Horsetail Dance by attaching a horsetail around the waist and prancing, in time with the drum, like a horse.” (Disneyland Backstage, Summer, 1965).

The Horsetail Dance at Ceremonial Dance Circle.

The Horse Dance.

The Horsetail Dance at Ceremonial Dance Circle.

The Horse Dance.

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE (1959)

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE (1959)

Stalking his game…

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE (September, 1959)

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE (September, 1959)

The colorful circular feathered pieces are called bustles, and are sacred regalia traditionally worn only by members.

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE (1961)

The Shield and Spear Dance.

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE (August, 1959)

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE (1957)

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE (1957)

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE

Toward the beginning of the show, the Narrator often invited “all our young friends to sit on these benches around the dance circle. They have been placed here especially for all you boys and girls so you can get a closer look at the dances and, also, so you’ll be close at hand for the happy surprise we have for you at the end of the program.” Any guests that were blocking the doorway would be invited to the seating area.

“Our forefathers had many primitive tools and weapons. Among these is the bow and arrow…”

Speaking of the bow and arrow, once the show began, there were occasional skillful presentations of archery. Pictured above is actually a game played with arrows, by members of the Pawnee. Here, we refer to it as the Pawnee Arrow Game.

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE, (October, 1960)

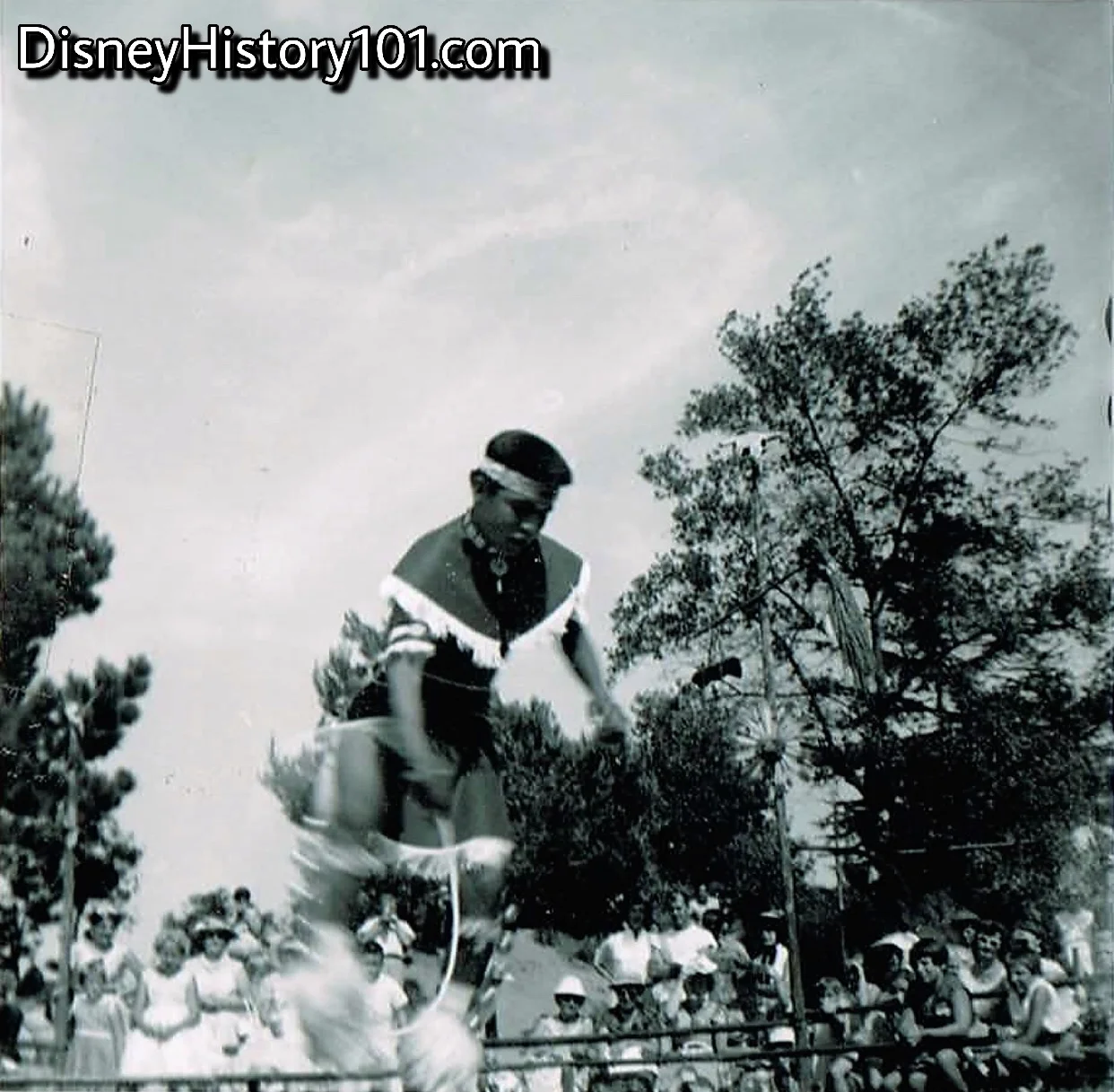

The Hoop Dance was another newer, contemporary dance that was demonstrated by youngsters. We’ll examine it a little later.

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE, (August 4th, 1960)

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE (August, 1958)

One of the skillful Tafoyas performs a Hoop Dance.

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE

And sometimes children (like the Oglala Sioux Lakota boy pictured), had the privilege to perform demonstrations for guests. You wouldn’t find a younger “Disneylander” anywhere else in the Park! Former performer “Dennis [Tafoya] recalled how meaningful it was for him and his family members to be able to spend so much time immersed within a community of Indian dancers and entertainers. They shared and learned Indian culture with Indian people of many different tribes, while serving as ‘cultural ambassadors’ to non-Indians.”

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE, (June, 1960)

Eddie Little Sky (on the left, in the red shirt) performs with one of the younger performers. This was a unique experience, for outside Disneyland’s Indian Village, you wouldn’t see any Disneylanders as young (Shoe Shine Boys and Disneyland News Carriers, included).

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE

Young and old Indian Village representatives could proudly share their culture with fellow Disneyland Cast Members or any guest who would wander down the trail!

Wallace Little (Eddie Little Sky's father), Dawn Little Sky (Eddie Little Sky's wife), and Robert "Little Beaver" (Eddie Little Sky's brother), (September, 1959)

As to the important role of American Heritage, Walt Disney once divulged that “our heritage and ideas, our code and standards - the things we live by and teach our children - are preserved or diminished by how freely we exchange ideas and feelings.” This philosophy of the free exchange of ideas and feelings was certainly in motion among the diverse representatives of the Disneyland Indian Village. The young, elders, and whole families also believed so strongly in what was being accomplished through the Disneyland Indian Village, that it became a common sight to see couples and practically whole families representing their Tribe and meeting Disneyland guests together here.

For example, Eddie Little Sky and his wife Dawn, both performed minor roles in Walt Disney Productions - Dawn had worked for Walt Disney Studios’ Ink & Paint Department, while Eddie had appeared in minor live-action roles. They both worked in the Indian Village together - naturally, Dawn narrated and performed dances, while Eddie also performed. Dawn and little Robert were occasionally featured in media (i.e. the Vacationland magazine pictorial published for Winter/Spring of 1965).

Other families (like the Cliffords of the Oglala Sioux Nation, and the Tafoyas of the Pueblo Nation) would also go to work for Disneyland together! The result of this family teamwork was that especially the children would learn much from this cultural share and gain a pride in their own cultural heritage. By the spring of 1967, the Disneyland Indian Village boasted 14 talented youngsters (seasonal and permanent), representing six tribes. These young ones participated in “140 half-hour shows a week (throughout the summer and on weekends and holidays)”, before “a million-and-a-half visitors each year”, according to Disney News (published Spring, 1967). The seasonal dancers (“who worked during the Summer months and then returned to their reservations and schools in the Fall”) were Evergreen (Joseph Herrera Jr.), Spotted Fawn (Ramos Suina), Eagle (Natividad Pecos), White Sea Shell (Ray Trujillo), Yellow Butterfly (George Cordero), Singing Blue Lake (Marcelino Trujillo), and Thundercloud (John Romero). The permanent dancers (“who lived in the Southern California area and worked weekends and holidays during the Fall and Winter months”) were Horse Stealer (Dan Jennings), Whitecloud (Leonard Tafoya), Red Eagle (Mike Tafoya), Little Deer (Dennis Tafoya), Whirling Wind (Ray Morton), Little Buffalo (Mike Miller), Beaver (Antalo Lester), and Princess Morningstar (Nancy Rubedeux). An enjoyable time was had by all that worked at Disneyland whether they were employed full or part-time.

With the exception of seasonal parade units or special performances, children did not routinely entertain Disneyland guests. So, the Disneyland Indian Village was truly distinct in this regard - featuring more children (ages 3-12) in addition to young adults among its free exhibits and shows, than anywhere else in Disneyland! The answer to why parents tribal councils, and (in some cases the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs) would permit these children to be involved in the Disneyland Indian Village is perhaps best summed in these words from an article published in Disney News (Spring, 1967), “Perhaps the best known Indians in the United States are the 14 young people who work in Frontierland, at Disneyland. With permission of their tribal councils, and in some cases, the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs, they perform ancient tribal dances for a million-and-a-half visitors each year. All are talented youngsters whose underlining purpose in working at the Park is to erase a long-held impression here and abroad that all a Indians are war-whooping savages capable of little else than forever galloping across television and movie screens. They have a proud heritage to talk about, and talk about it they do. In their colorful performances, they contribute to a broader understanding of Indian traditions, while at the same time dedicating themselves to preserving the customs and arts of their people.” In the words of Walt Disney (published in Wisdom magazine, December of 1959), “All of us whether 10th generation or naturalized Americans, have cause to be proud of our country’s history.”

An Unidentified Indian Village Performer, (August, 1959)

These are the true-life peoples of the Indian Village.

Louis Heminger (CHIEF SHOOTING STAR) displays Disney Courtesy with a smile and little gestures towards guests, c.1960s.

Louis Heminger (CHIEF SHOOTING STAR), (1950s)

(August, 1958)

These were the faces of Frontierland’s Indian Village - both youthful and wise!

CHIEF SHOOTING STAR, (August, 1958)

Many tourists like Matthew, his sister, and Pat their mother enjoyed visiting the Indian Village and meeting new friends like honorary Sioux Chief Shooting Star! Chief Shooting Star appeared in many Hollywood westerns (including the Davy Crockett television series), before working three years at Disneyland. As mentioned earlier, he was present to welcome five-year-old Elsa Bertha Marquez (the one millionth visitor) and her family to Disneyland on September 8th, 1955. He continued to welcome and treat each and every visitor as if they were a Disneyland V.I.P. After retirement, he was active with the Indian Center in Los Angeles. You may recall, that his son Ron went on to also work for Disneyland, operating Fantasyland’s Storybookland Canal Boats. As for Ron, he spent some time at Walt Disney World.

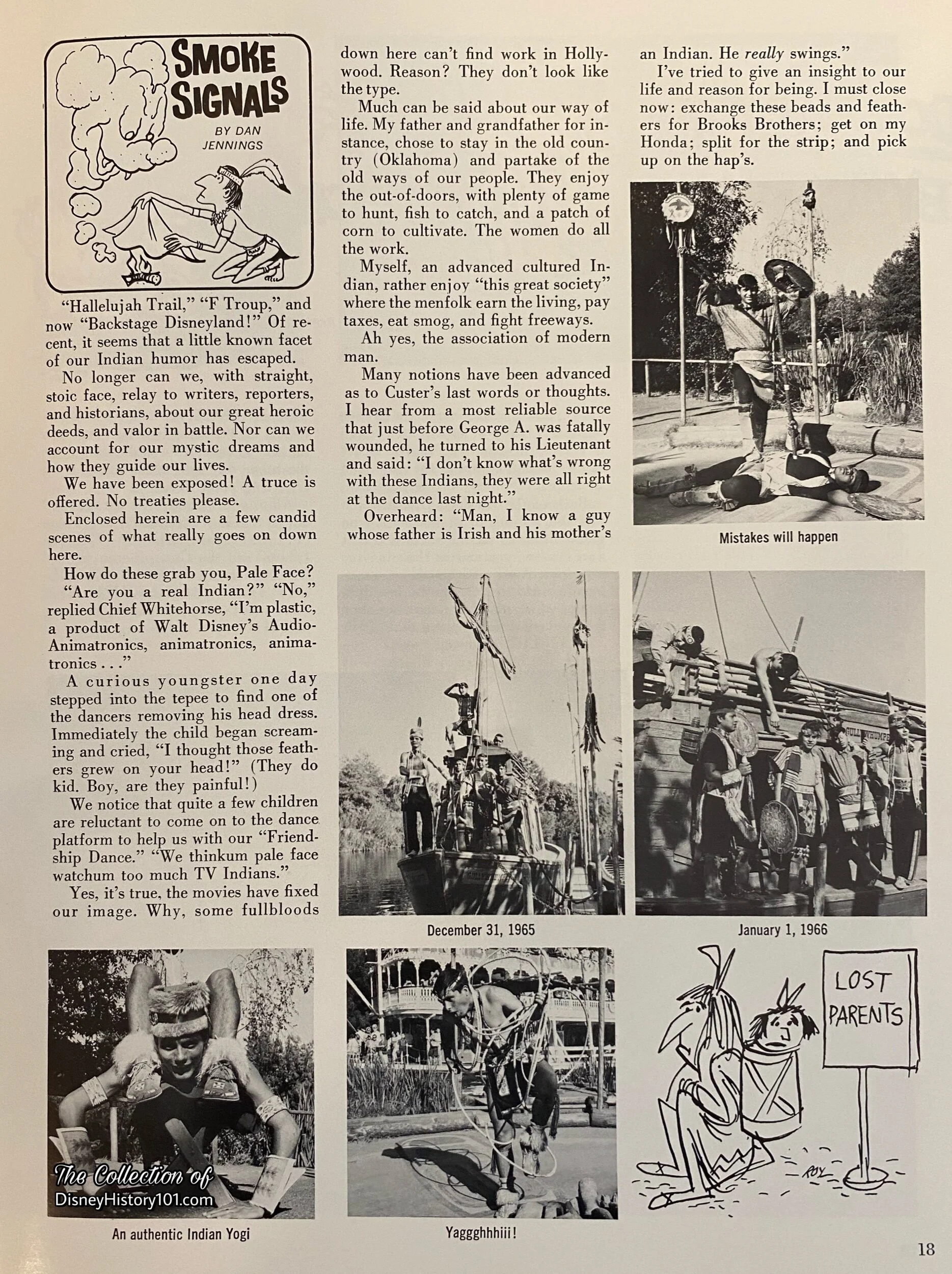

“Smoke Signals” Article, “Disneyland Backstage”, (Spring, 1966)

The “Disneyland Backstage” publication informed Disneyland employees of what was going on at the Park, and allowed an opportunity to have a little fun! A testament to this, is this month’s “tongue-in-cheek” “Smoke Signals” column contributed by Indian Village full-time performer Dan “Horse Stealer” Jennings (for the Spring, 1966 Issue of the Cast Member-only periodical). He is assisted in his hilarious “send-up” of Indian Village Cast Member life, by some of his young contemporary performers (seen in the accompanying photos).

In addition, some youth would often go on to carry the legacy of their parents and their Tribe, and even carry on a career with Disneyland. For example, original Indian Village performer John Knifechief was later joined at Disneyland, by his fifteen-year-old son Tom in 1963. Riley Sunrise’s son Helmuth would eventually go on to develop an important and life-long career outside the Disneyland Indian Village, in the Disneyland Custodial Department. Louis Heminger’s son Ron Heminger went on to also work for Disneyland (both operating Fantasyland’s Storybookland Canal Boats, and becoming the Peter Pan Foreman by 1966). Ron would later move on to greater managerial roles at Disneyland and Walt Disney World in Florida. As for Dawn Little Sky and Robert "Little Beaver" (pictured above), they would appear in promotional Disneyland publications and brochures (like “Information For Your Visit To Walt Disney’s Magic Kingdom”, published 1962).

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE, (June, 1961)

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE, (1959)

Speaking of Hoops, young guests were invited into Ceremonial Dance Circle (at the end of each performance), to join hands and perform the circular Friendship Dance! Walt Disney’s Guide to Disneyland (published 1958) depicts this dance, variously referring to it as the Indian “Feast Dance”.

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE

CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE

Truman Dailey proved that “Disneyland is For People!”

“Good afternoon friends, Welcome to The Indian Village.” -Truman “Chief Whitehorse” Daily (1898-1996).

Before coming to Disneyland (in 1960), Truman Washington Dailey (of the Otoe tribe) “made his living by farming and raising livestock” on a reservation in Redrock, Oklahoma, according to Disneyland Backstage magazine (published for Summer of 1965). This was in addition to serving as a leader of his tribe. Now, retired “Chief White Horse” (also known around the Disneyland Indian Village as Truman W. Dailey) welcomes one of the younger guests to Disneyland’s Indian Village! Truman was so approachable and known for giving special priority to making younger guests feel comfortable and welcome, that when Disneyland ran a “Disneyland is For People” advertising campaign, Truman was featured with one of the younger guests. He was photographed with young actor Kevin Corcoran (bestowing upon him the status of honorary member of his Plains Indian tribe), for a Jack and Jill (May, 1960) article and photograph. Truman was also featured interacting with a young child, among a collage of photos on the cover of the “Disneyland ‘U.S.A. Summer 67”! Truman is one of many Disneyland Indian Village representatives that receive some screen time in “Disneyland Showtime” (a c.1970 Wonderful World of Disney episode) featuring Kurt Russel, E.J. Peaker, and the Osmond Brothers.

Truman Dailey and Guest

Chief White Horse (Truman W. Dailey) near the Western Plains "Teepees"

Truman stands poised for a photo, while dressed for cold winter weather.

(c. August, 1959)

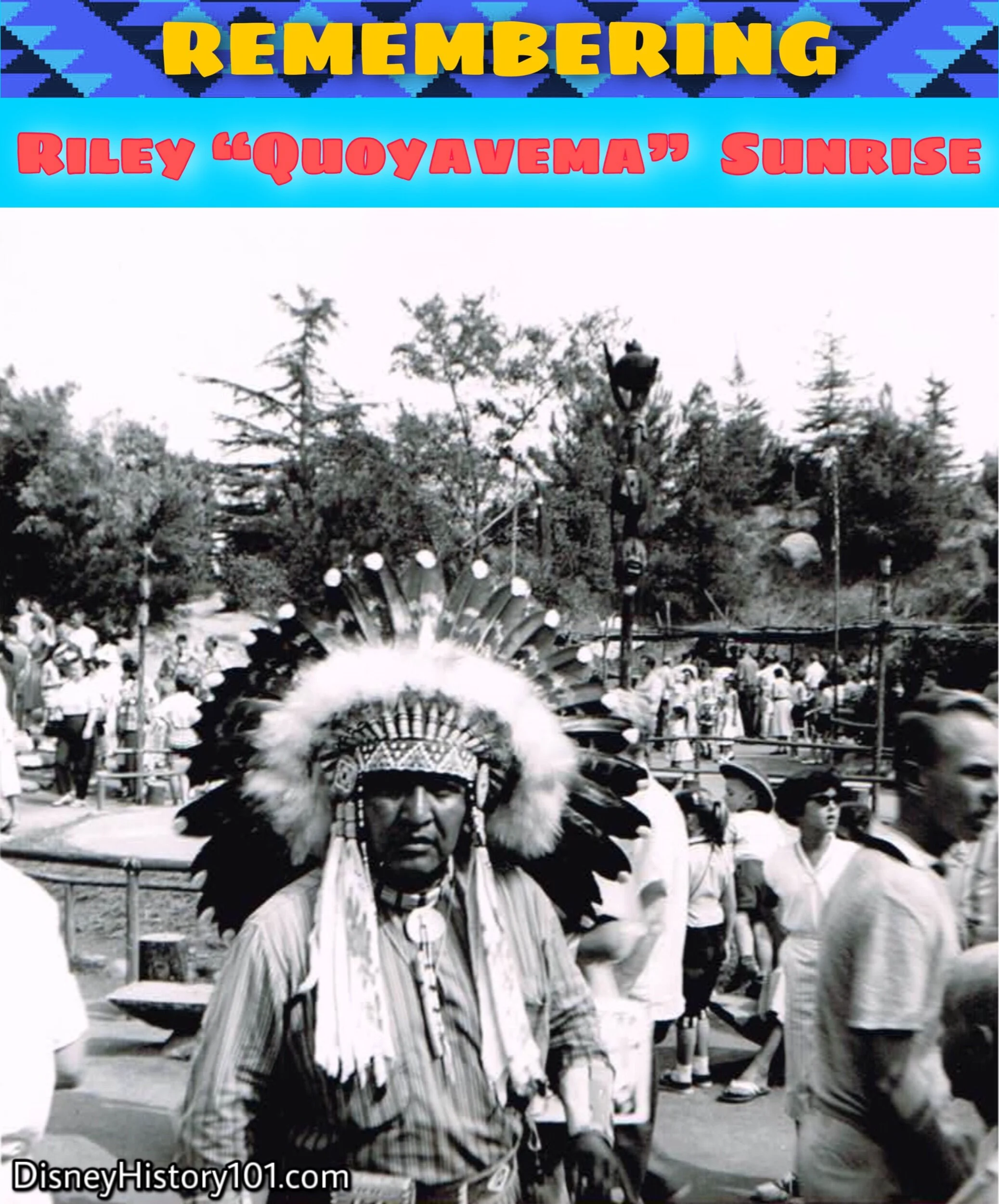

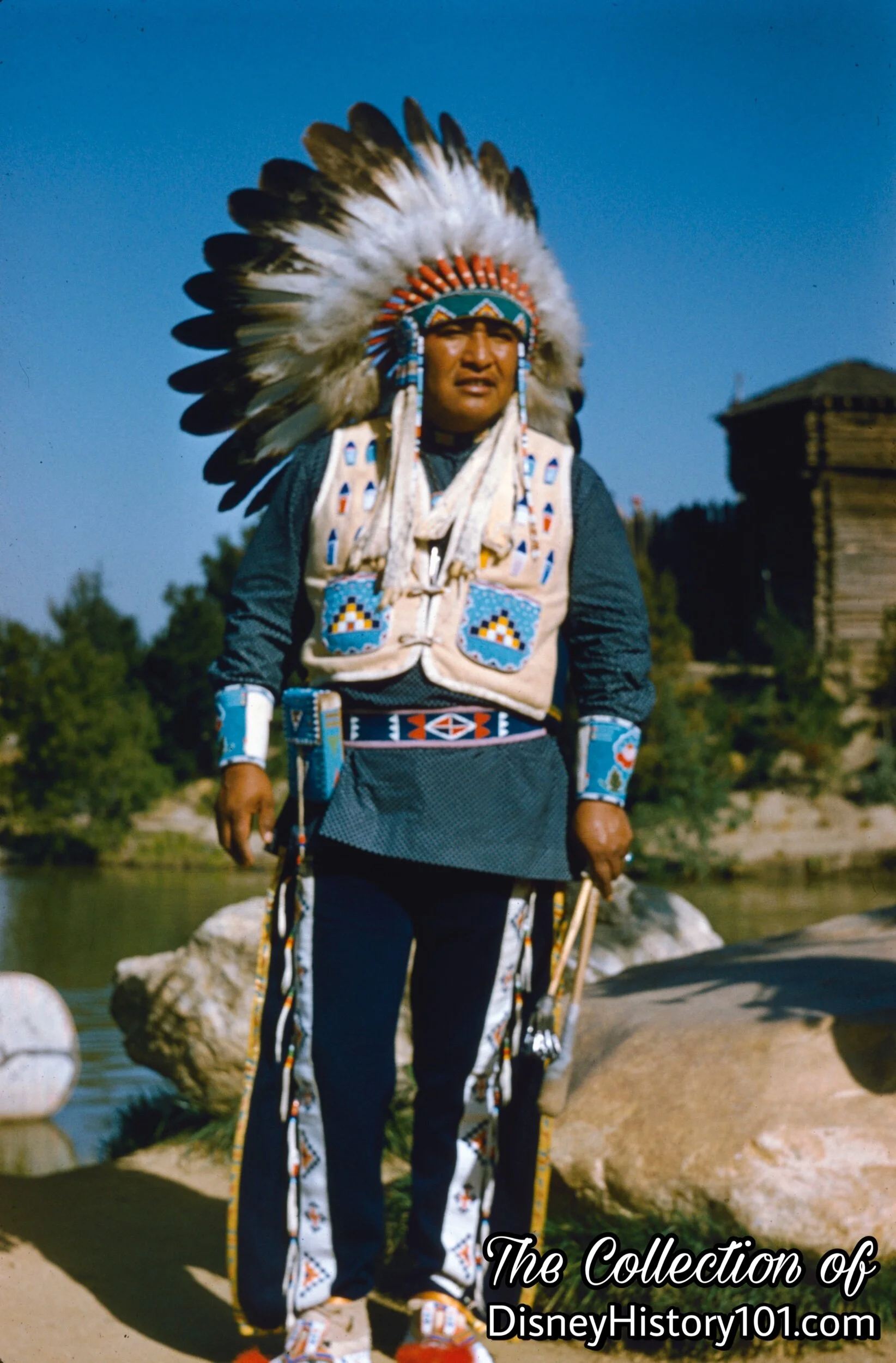

Chief Riley “Quoyavema” (Kwayeshva) Sunrise (1914 - 2006) of the Hopi Pueblo was born in Anadarko, Oklahoma, and adopted by a Kiowa family. The name Quoyavema means Sunrise to the Hopi of Arizona. He lived at Second Mesa, Arizona, on the Hopi Reservation before acting small roles in several films. His filmography includes The Thing from Another World (1951), Annie Get Your Gun (1950) and Border Incident (1949). According to Disneylander (May 1957), “Before coming to Disneyland, Sunrise was the Counselor on the American Indian; teaching Indian Crafts and dancing at the Black Foxe and Page Military Academies in Los Angeles. He also designed the Apache Drum Majorette costumes for the Presidential Inauguration parade in Washington, D.C.”

Eventually, Quoyavema would apply for Disneyland and contribute to the cultural share within Disneyland’s Indian Village. Riley can be seen (likely co-emceeing, while) sitting with Louis Heminger in “Disneyland U.S.A.” (released by Buena Vista Film Distribution, December 20, 1956). Above, Riley poses for a guest’s camera, while standing in the same portion of the Stage, during August of 1959. He can be seen wearing the traditional eagle feather “war bonnet” of the Lakota. According to friend David Lewis, “Riley was actually a Hopi, so he respectfully asked the Lakota elders for their permission to wear their regalia [including the ‘War Bonnet’]. He told me that had he not received their okay, he would not have accepted the job.”

Even while contributing to the cultural share at Disneyland, Quoyavema still continued to volunteer. The Disneylander (May 1957) shared: “Sunrise is a member of the Advanced Explorers of the Boy Scouts. He is teaching Folk Lore and Indian dancing to groups of Girl Scouts, Brownies, and Bluebirds. The little girls were so grateful for his help that they surprised him with a cake. After the Easter week here at D/L, and before the summer season starts, Sunrise is returning to Indiana for a visit, but it seems that he will not have much rest as he has been booked for 17 lectures throughout Indiana Schools.”

Riley Sunrise, (late c. 1950s)

Former Indian Village performer Cheryl Clifford has fondly remembers Riley : ”I knew him as Chief Sunrise (out of respect). He wore a full headdress, and he would get on the drums, and dance sometimes (though he was a little slower). When we first came to the Indian Village, he [Riley] said, you need to have an Indian name. So, Riley gave me my Indian name “Sunflower”. My brother was “Iron Shield”. Riley also gave him that name.”

After working for Disneyland’s Indian Village, Riley went on to produce many paintings of Katsinam which are preserved in the Denver Art Museum, Gilcrease Institute (Tulsa), and the Southwest Museum.

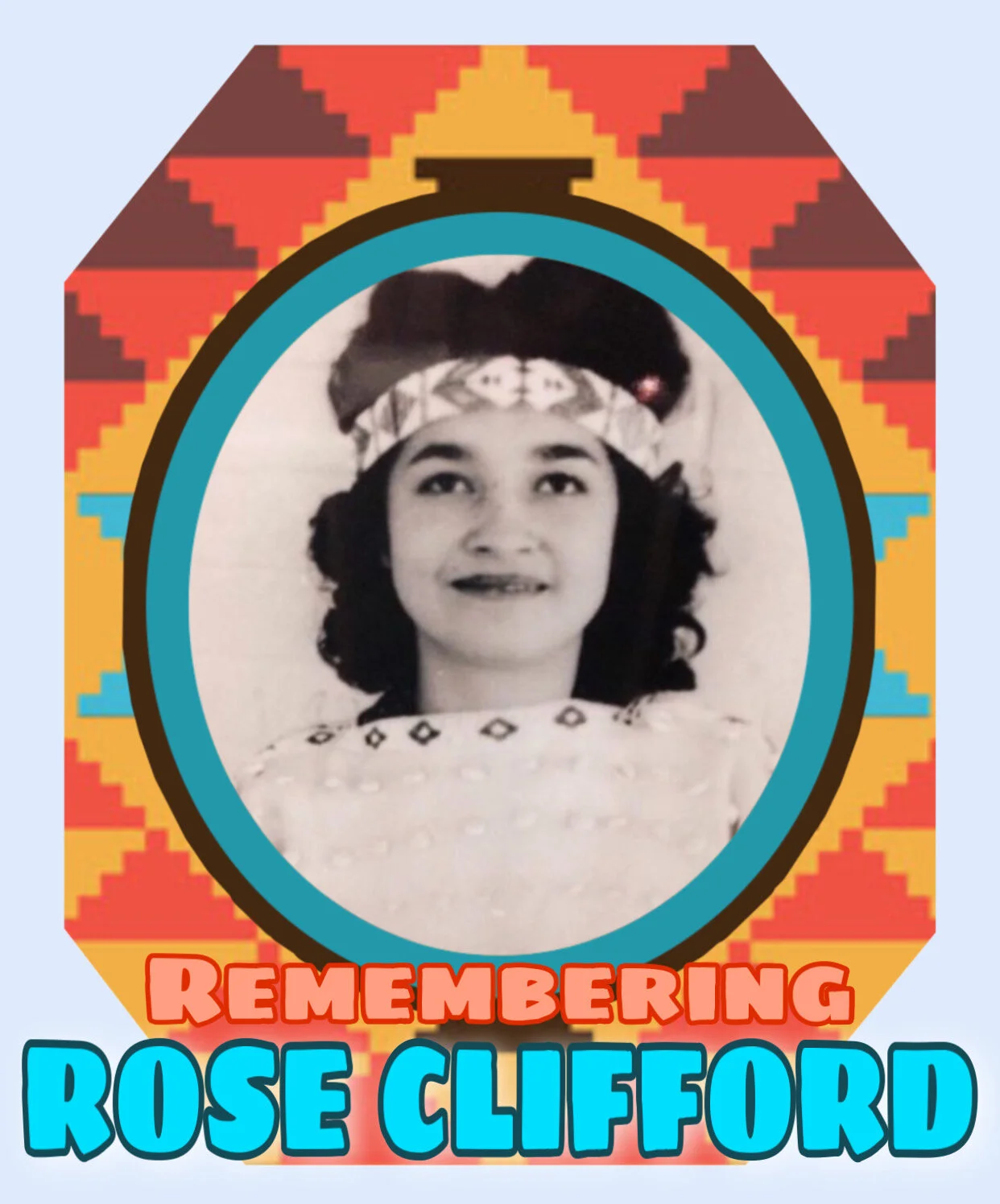

(Photo : Courtesy of Mike & Jessica Clifford ; with a deep appreciation to the Clifford family)

There were many skillful and valuable women that also contributed greatly to the cultural center that was Disneyland’s Indian Village. In addition to creating beautiful works of beadwork, wool, and clay, a few of the women also occasionally participated in dance demonstrations in Fire Dance Circle. Cheryl remembers how her mother Rose Clifford came to become involved :

“My mom’s [maiden] name was Rose Pourier (a French name). About 1955, my mom was almost in a movie. She was asked to be in a movie starring Robert Taylor, and play an Indian woman whom he had kidnapped, in “The Last Hunt” (it had to deal with the last of the white buffalo). My mom was pregnant at the time, and she would have been too big at the time of filming, so Debra Paget ended up playing her in the end.

Eddie Little Sky had been reading about mister Disney putting together an Indian exhibit. He, Vincent St. Cyr, and my family were involved in dancing and going to “pow wows”, and we were hired right on the spot no problem. My mother was the first one involved, out of the family . Dad took care of business. He was a very hard worker, and put in many long hours. Eddie Little Sky picked us up. At the time we lived in Long Beach. Back then, you would take side roads all the way to Disneyland. It was close to a 40-minute drive from Long Beach to Disneyland, and it was a long commute in the early morning hours.

There were a couple of Navajos that did the sand painting , my mother did bead work, and another was a silversmith (if I remember correctly). My mother made earrings, and medallions that would go around her neck. The beads were genuine from Indian Shops (from places around Los Angeles), or people would get the beads for her from South Dakota. She would wear these. My mom had one dress that was bright blue with ribbons, and she would wear that when it got really hot. Sometimes she would wear the original buckskin (not beaded, beautiful reddish-tan) with real elks teeth.

…Men usually danced in the circle, doing their dances, and the women traditionally stood to the side. That was the way of the Oglala Sioux. These were the dances that were handed down. My mother did dance to. There were a few dances for the women…She would come out and dance for the “Circle Dance” - all of us would get on stage at the end of the session. We were probably more in the “inner circle”. You start out with a small group of people (the little kids first), and then the circle gets larger (adults and finally the kids that were more shy).

She can be seen inside the Official Guide to Disneyland [1956] - she’s the only female that stands with the guys. Walt liked my mom because she was very easy to talk to. Each morning, he would walk through the tunnel and into the village, and say good ‘Morning, Rose’.

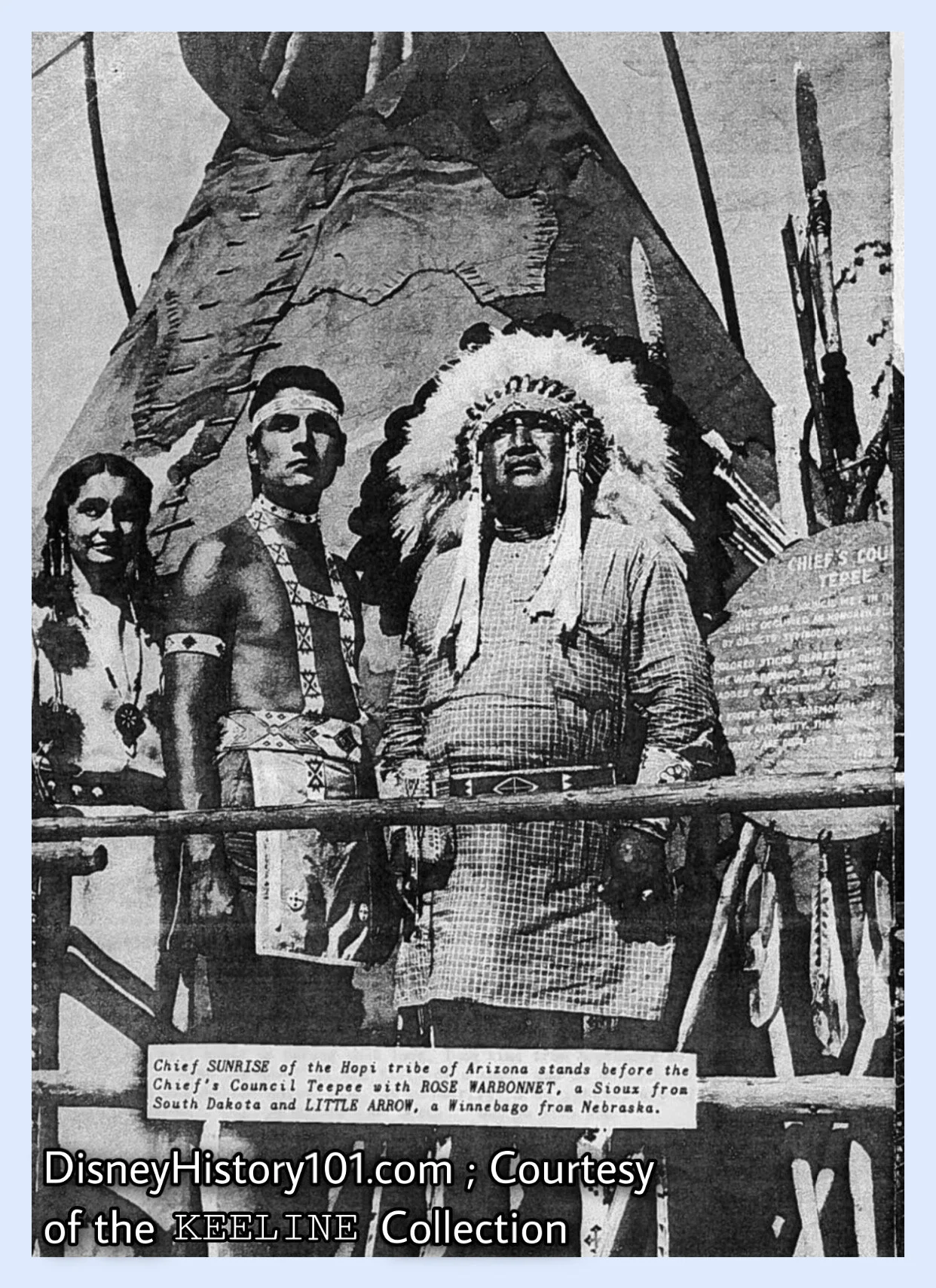

Rose “Warbonnet” Clifford (left) in "Disneylander" magazine, (September, 1957 ; Volume 1, Number 8 ; Excerpt)

By this time of this publication’s release, the Disneyland Indian Village was relatively new (only a year old). Rose Clifford can be seen with other prominent Indian Village members Little Arrow and Riley Sunrise in this photograph featured in Disneylander magazine.

"CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE"

"CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE" (October, 1960)

"CEREMONIAL DANCE CIRCLE" (c. May, 1960)

"THE ENTERTAINMENT COSTUME DEPARTMENT" (October, 1960)

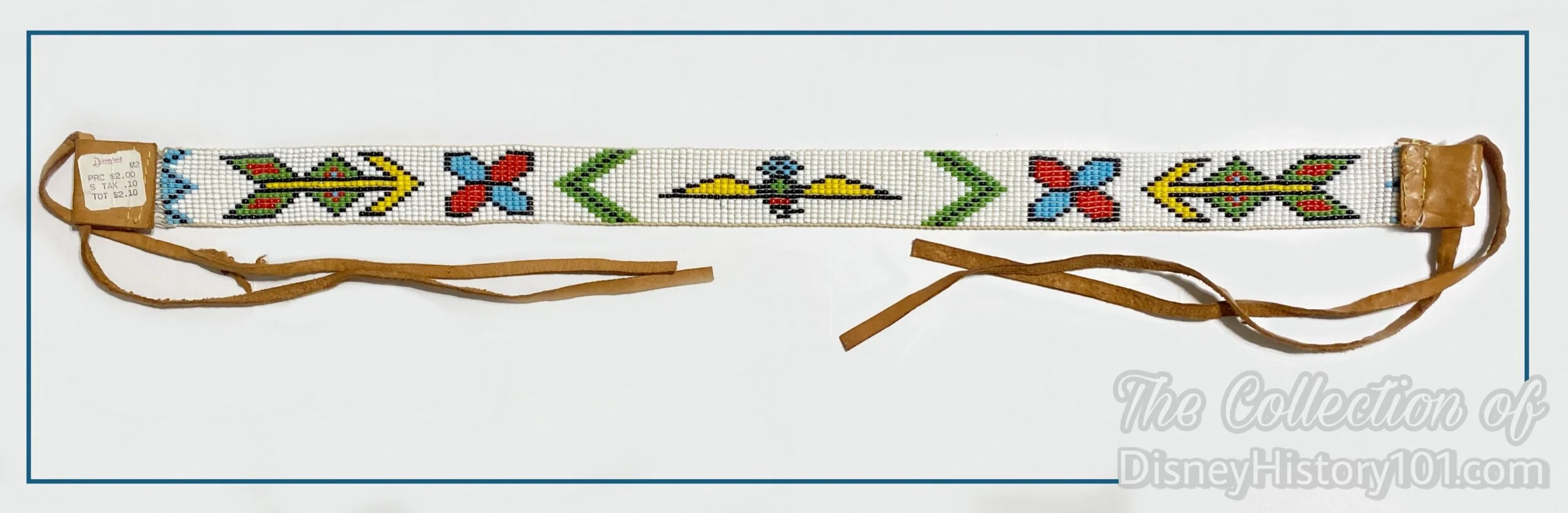

“Your Disneyland: A Guide for Hosts and Hostessess” published 1955: “If you wear a costume furnished by Disneyland, it must be clean and fresh at all times.” In step with this Disney Tradition, a riverfront awning located next to the "CHIEF'S COUNCIL TEPEE" exhibit protected the Indian Village costumes (like the brightly feathered bustles, warbonnets, bells, and roaches), when not in use. Can you identify some of the costumes and accessories used to perform the “Shield and Spear”, the “Eagle”, or the “Hoop Dance”?

Unlike the other Disneylanders, Indian Village employees often brought their costumes from home. These pieces (i.e. breechcloth, dresses, belts, etc.) were often made by themselves, family members, or others skilled in the craft. According to Wardrobe Bulletins, the Indian Village was the only Disneyland land where employees were permitted to wear tan Indian moccasin shoes while working their shift. Still, the Disneyland look emphasized natural good qualities, and habits of neatness and cleanliness.

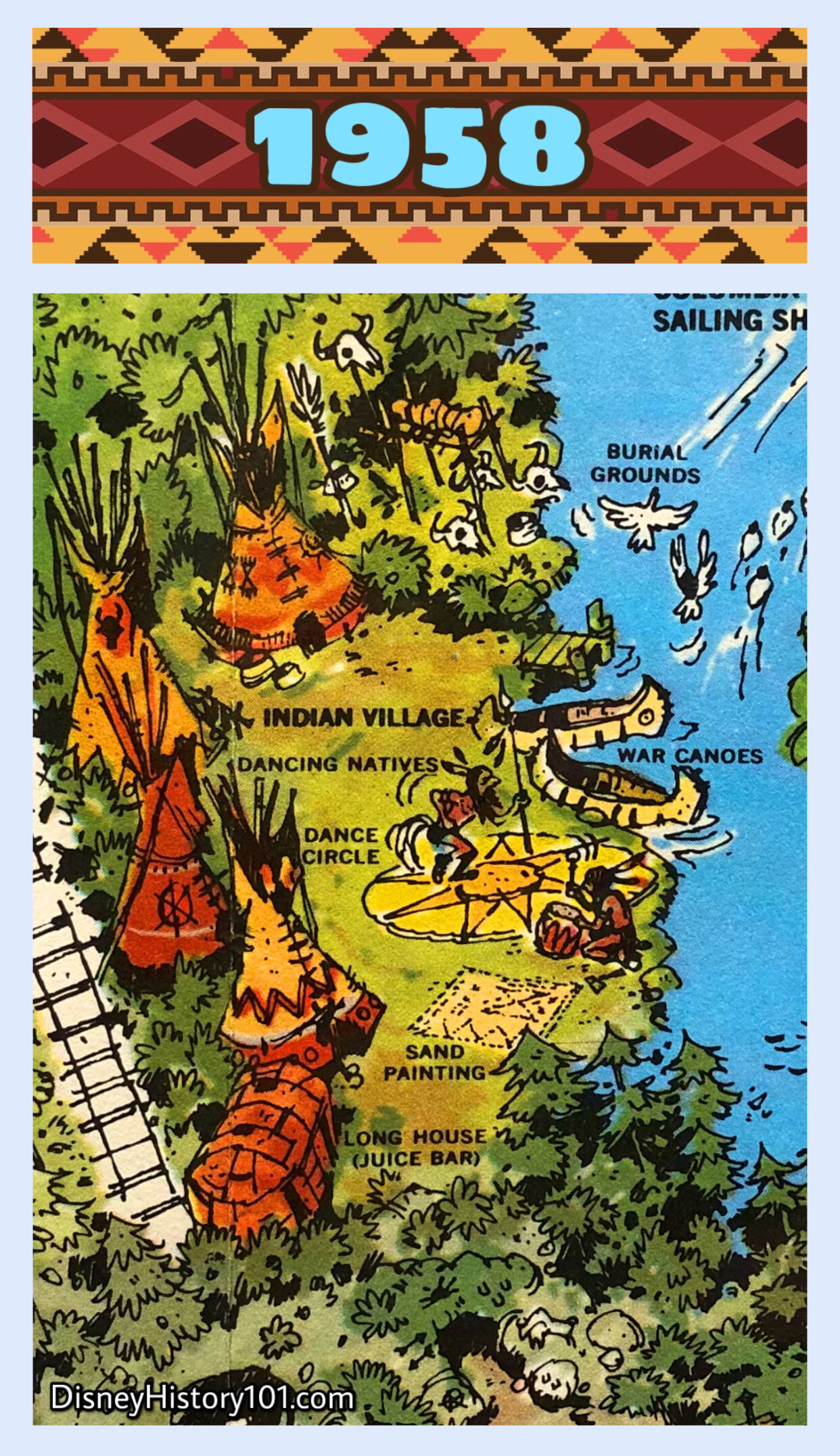

THE NEW INDIAN VILLAGE - Disneyland Map by Sam McKim, 1958

Now, “Disneyland is a place to have fun… and with the fun it is a place where you can learn,” according to “Disneyland, U.S.A.” (published 1958, for potential Participants). Two years after opening, the Indian Village continued to grow and expand with new exhibits and activities that await visitors in the Disneyland Indian Village.

Al Alvarez recalled: “In 1958, I transferred to the Indian Village to help Hank Dains put up tepees in the Village. We also put up the tepees on Tom Sawyer's Island.”

This close-up of a (c.1958) Disneyland Map (pictured above), details some of those additions. Its “hub” or “plaza” was the slightly-elevated “Dance Circle” where demonstrations were held. This was centrally located next to the “Chief’s Council Tepee”. Around this”hub” were other tepee exhibits. According to a sign posted near the entrance : “All of this equipment was created especially for the new Walt Disney Feature Motion Picture Westward Ho The Wagons.” There was also a facsimile of a Burial Ground, and a Navajo Sand Painting exhibit.

In 1958, Jimmy Durante performed live radio from the Indian Village.

"MEDICINE MAN'S CEREMONIAL TEPEE"

This exhibit was “filled with the mystic and intriguing objects of this vital craft” according to “A Visit to Frontierland’s Indian Village”, in the Disneyland News Newspaper (July 1955 - March 1957).

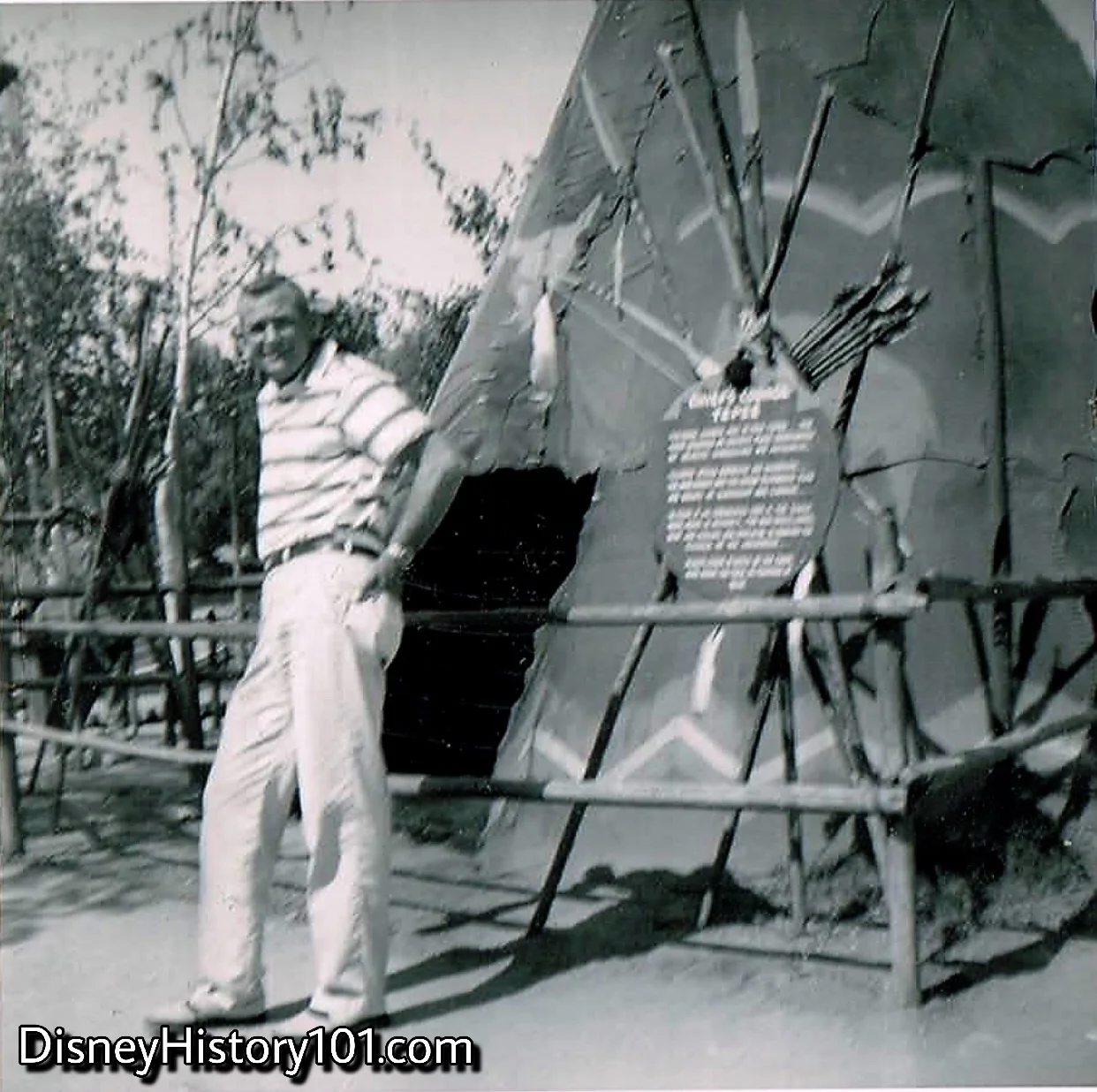

"CHIEF'S COUNCIL TEPEE"

According to the description on the tanned skin :

“The Tribal Council met in this tepee…The chief occupied an honored place, surrounded by objects symbolizing his authority…Colored sticks represent his warriors…The War Bonnet and the Indian Feathered Flag are badges of leadership and courage…..In front of his Ceremonial Pipe is the eagle wing, mark of authority…the war shield, lance, bow, and arrows are displayed to remind the Council of his greatness…scalps taken in battle by the Chief hang above the tepee as trophies of war.”

"CHIEF'S COUNCIL TEPEE" (August, 1958)

Each tipi came to feature a “tanned hide” bearing a description of the task that its inhabitant performed!

"WARRIOR WRITES HIS LIFE STORY WITH PICTURES ON RAWHIDE"

The tanned skin near this exhibit continues : “Using nature’s colors ground from rock, earth, roots, and animal glands, his brushes are made of porous bone from the buffalo.”

"WARRIOR'S TEPEE", (October, 1969)

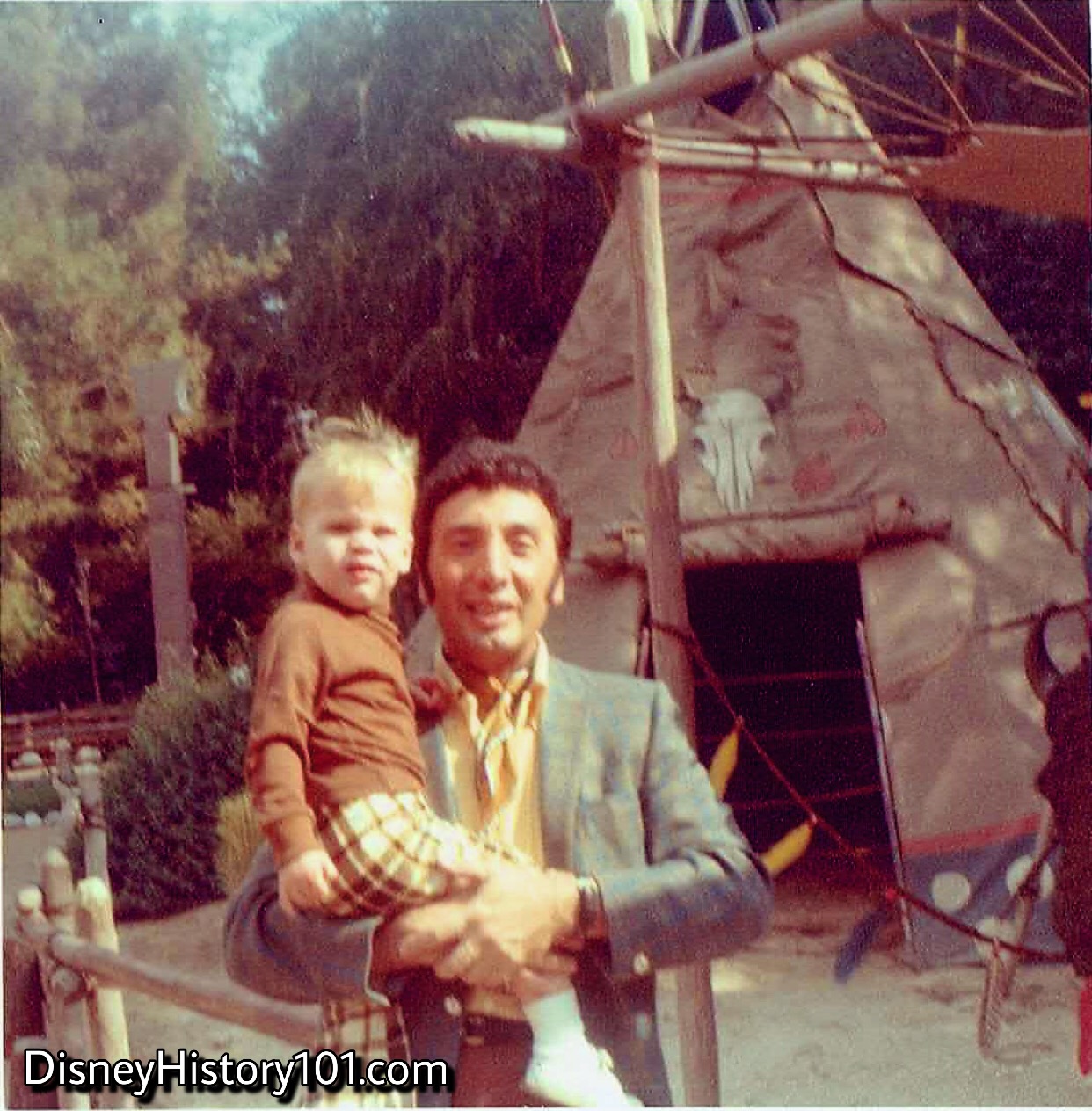

Guests like young Michael and his father took advantage of photographic opportunities near the Indian Village “Warrior’s Tepee”.

"CHIEF'S COUNCIL TEPEE", (c. July, 1967)

"CHIEF'S COUNCIL TEPEE", (c. April, 1964)

“Even waste receptacles have the Disney touch, each ‘land’ having containers designed for its theme and period”, according to The Disneyland News (Vol.1, No.1 ; for July of 1955). In the foreground sits one of those custom waste receptacles, disguised as an ordinary log.

"CHIEF'S COUNCIL TEPEE", (June 12, 1964)

The interior of the tipis featured dioramas to show what life was like in an Indian Village. If you look closely through the entrance, you can see the rope netting used to protect the displays.

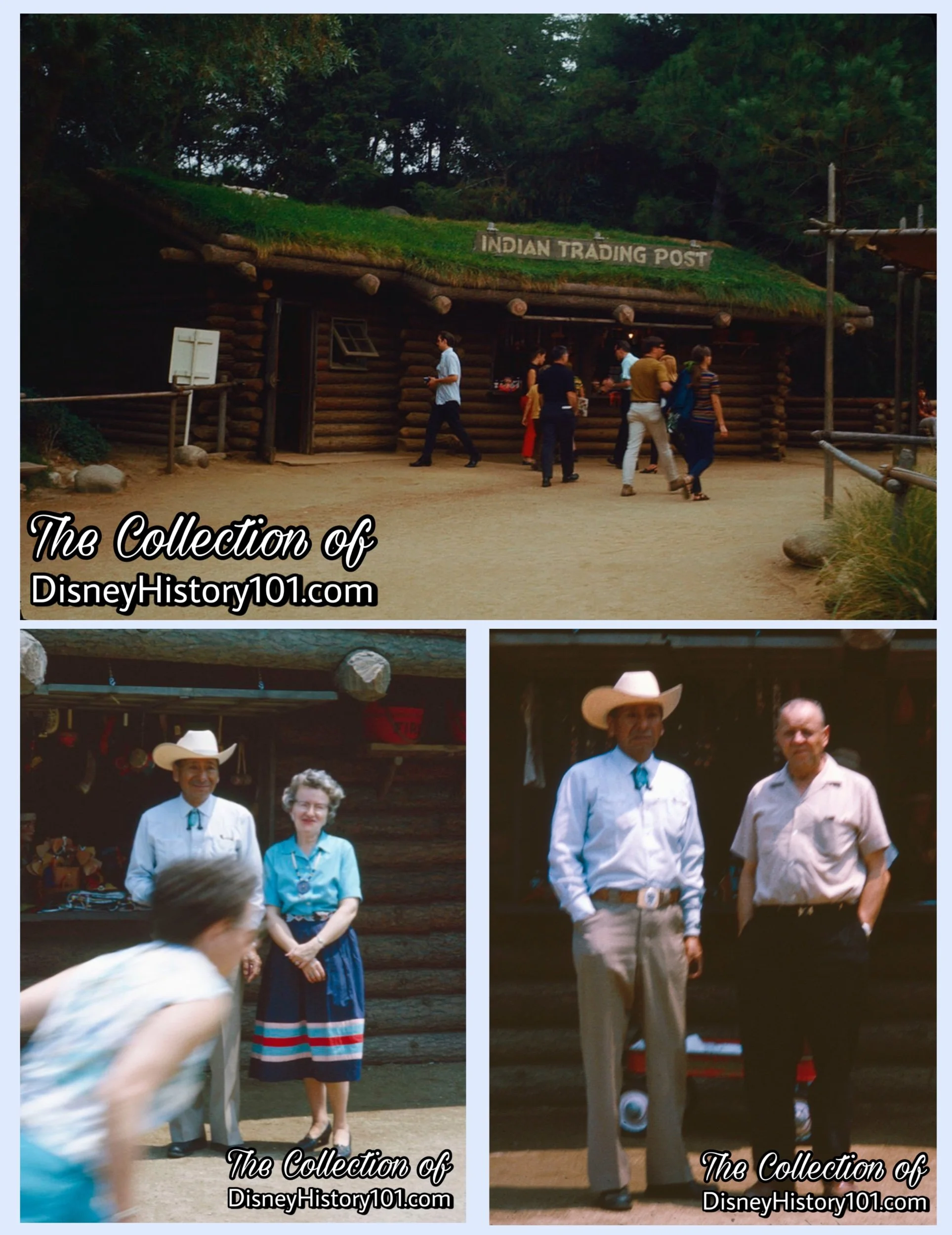

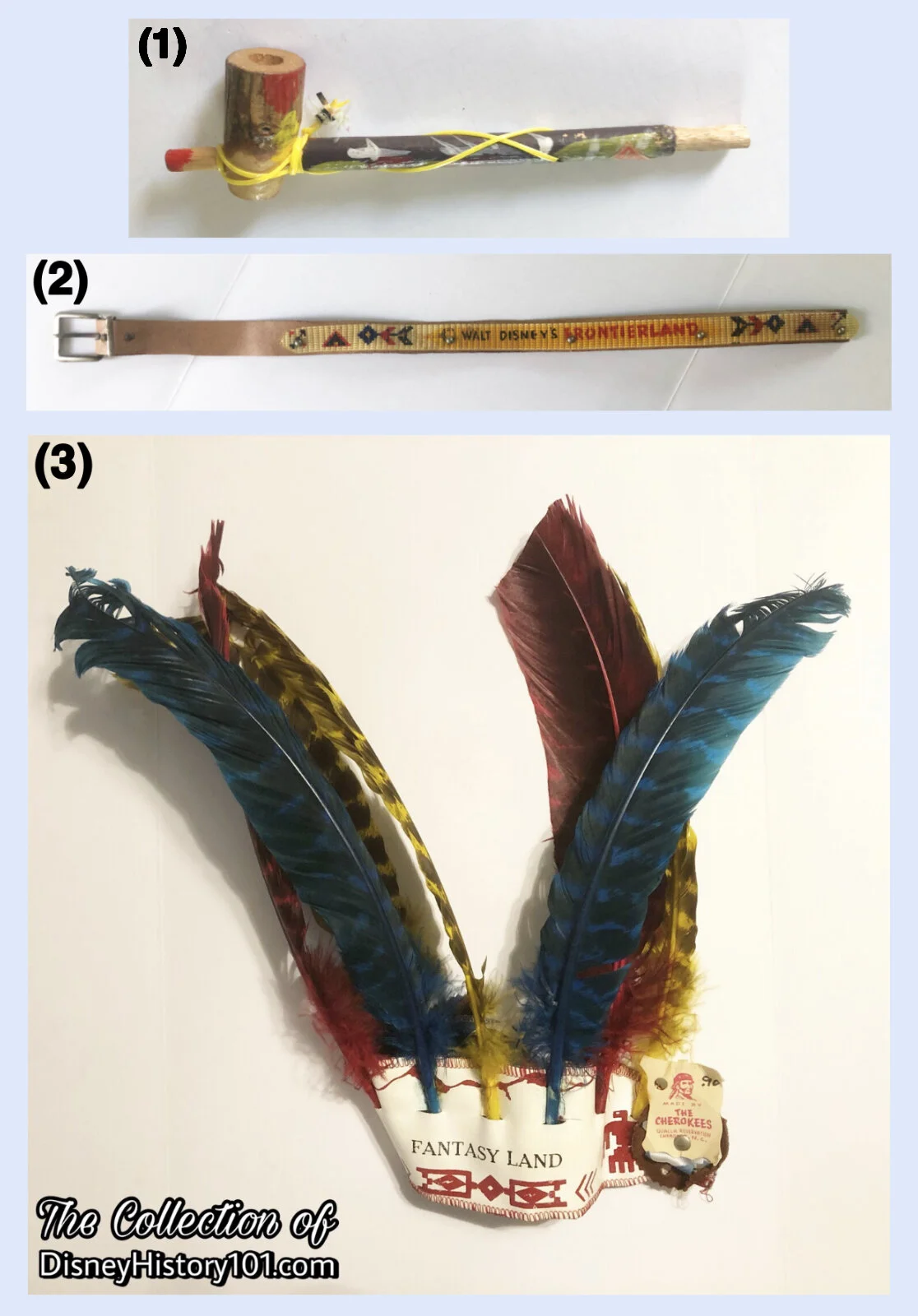

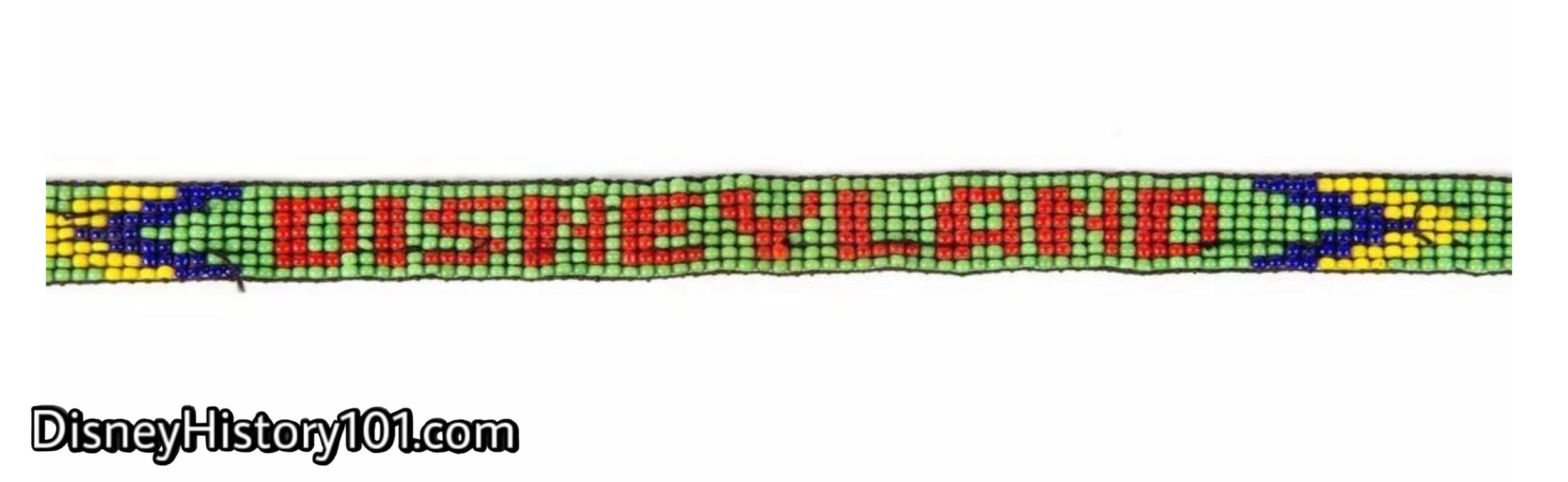

THE INDIAN TRADING POST (INDIAN STORE)

Notice the hand-made wares in the background of this and the following photograph. Adults were usually attracted to the unique, hand-made turquoise jewelry, clothing, and pottery available exclusively at the Indian Store (soon known as the Indian Trading Post).

The 1957 TWA brochure “Let’s Talk About… My Visit to Disneyland, Anaheim, California: A Note from Mary Gordon TWA Travel Advisor” mentioned: “We learned that to fully explore Disneyland takes two days, so early next morning we were at the gates of the park again. The second day we spent more time shopping in the 50 inviting shops, and the youngsters bought inexpensive souvenirs to take home to friends.”

The synergistic relationship between the commercial lessee William Wilkerson and Disneyland was good. William Wilkerson’s Indian Shop yielded some revenue for Disneyland Inc. - $4,253 for the fiscal year ending September 29, 1957 and $3,256 for the fiscal year ending September 28, 1958.

THE INDIAN TRADING POST (INDIAN STORE)

Of course the real attractions of the Indian Village were still the inhabitants - the talented performers and genuine ambassadorial representatives of each tribe! Many Disneylanders fulfilled roles at this merchandise location. Shirley Lovell worked this shop during 1955-1956, while in its original location. Lucette Albillar was in the area, c.1966.

Navajo Wool Carding, July 13, 1957

This was not the first time that the Navajo wool-carding craft was practiced in Disneyland. Like Spider Woman, Juanita “Kbaha” Lickers used traditional Navajo looms to demonstrate the art of weaving and manufacture similar wool rugs and blankets sold in the Davy Crockett Arcade Shop during 1956. By 1959 wool carding and weaving was demonstrated at the Indian Village during peak seasons and on week-ends. Long after the Disneyland Indian Village disappeared, Westward Ho Trading Company continued to sell authentic Navajo baskets and rugs (because they were still so popular).

Navajo Sand Painting, July 13, 1957

Sacred stories of the Spirit People are told through the sand paintings. All the painting is created through the right hand, in the direction of the movement of the sun. The colors are ground and mixed from (not sand, but) “carbon, vegetable substances or hairs from a black animal, and pulverized minerals. Some paintings are less than a foot in diameter, others are so large that it is possible to make them only in hogans built for the purpose. The small paintings can be completed by two or three persons in less than an hour. The great ones demand the work of fifteen men during most of a day. Occasionally paintings are done in the open air, but more often inside, and they must not be done after nightfall.” [“The Navajos of Monument Valley,” People and Places]

Navajo Sand Painting, (1961)

Here, skillful Navajo artists made sand paintings before guest’s eyes (and outside the traditional hogan, with the approval of elders). These were demonstrated at Disneyland, as early as the institution of the New Indian Village in 1956. According to “The Disneyland News” (Vol.2, No. 2 ; August, 1956), “Sand painting is one of the oldest forms of religions and artistic expression known. Each day the design is different. Normally he works the entire day on the painting, using bright colored sand to form the pattern. When finished, late in the afternoon, the painter must then erase the painting by performing a ceremonial dance. Until all trace of the colored sand has disappeared he continues the dance.”

INDIAN VILLAGE EXPANSION, c. 1965 / 1966

This is a rare “Vintage View” of the Indian Village featuring a maintenance vehicle near a construction barrier. Big changes were headed to the Rivers of America during the summer of ‘66 - with the opening of New Orleans Square!

Disneyland Map Excerpt, 1965

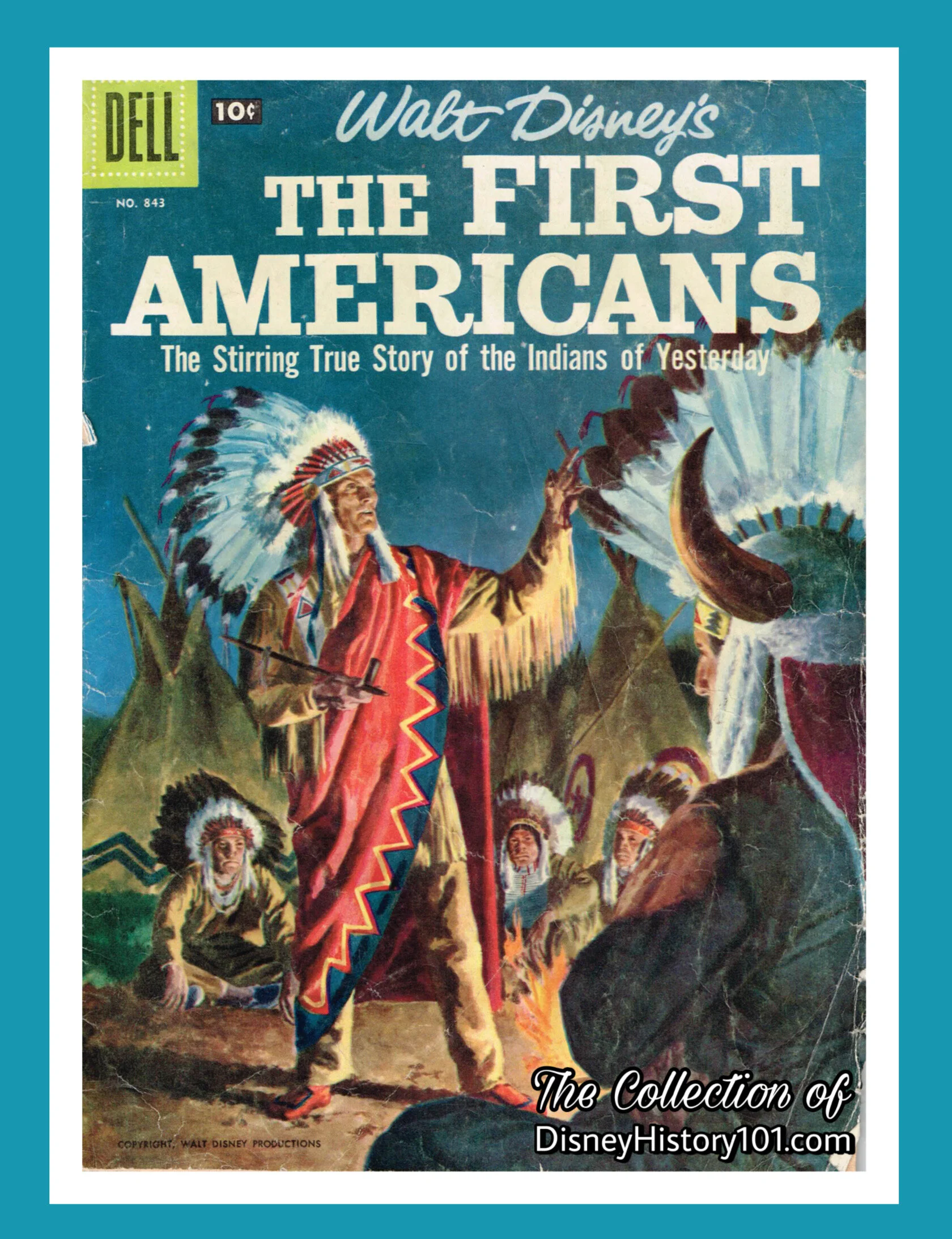

Disneyland Indian Village was a success, inspiring, similar attractions at other theme parks around the world. For instance, Freedomland opened in New York, in 1960, with a “genuine Indian village, where you'll see real Northwest Indians, making authentic Indian handicrafts in their own homes. Freedomland also boasted a “real Chippewa Indian war canoe,” paddled by guests, and with “Indian guides” leading the way past wooded islands and waterfalls.